![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

ANTHROPOLOGISTS, as everyone knows, are people who “go to the field.” Frequently pictured, or at least imagined, wearing the pith helmets and khaki clothing of someone’s colonial past, anthropologists are charged with the task of recording native customs, deciphering savage tongues, and defending beleaguered traditions. Following the prescription of the founding father of ethnographic fieldwork, Bronislaw Malinowski, they are supposed to immerse themselves in the culture of the other and emerge decorously shaken but professionally unscathed to report their findings to scientific societies, professional associations, and crowded lecture halls.

The actual experience of fieldwork is, of course, quite different. As every fieldworker knows, the reality is far from romantic. The natives are sometimes far from friendly. The states in which natives live are far from welcoming. Even the reasons we do fieldwork itself are increasingly under siege. Finally, and often most perplexing of all, the natives tend to ask more and harder questions of the anthropologist than the other way around. Indeed, for me, the hardest questions about fieldwork have always come from the natives—in my case, Quechua-speaking peasants living in southern highland Peru. “Why are you here?” they would frequently ask. “And what are you doing?” “Are you looking for gold?” “What are you writing down now?” “Why didn’t you write down what I just said?” Sometimes they asked if I was crazy. Why else, they reasoned, would anyone want to come there of her own free will (unless she were looking for gold).

The peasants with whom I lived in southern highland Peru were probably right to be perplexed about the mysterious nature of my mission (which was to study their fiestas, fairs, history, and culture). They did not take long, however, to find some more practical niche for me to fill: I became the resident community photographer. Indeed, some months I spent more time taking, developing, and distributing snapshots than anything else. At first I volunteered both my services and the photographs. Soon, however, as my dwindling grant monies flowed into the multinational coffers of Kodak and the somewhat more rustic cash registers of Cusco’s photographic studios, I found that I needed rules. If a family wanted more than four poses, I made them pay for the extra pictures. If they wanted multiple copies, enlargements, or identity-card portraits, the same rule applied. I marveled at the rapidity with which they learned to exploit their local representative of what Walter Benjamin has dubbed the “age of mechanical reproduction.”

I also marveled at the poses they chose. They were, of course, familiar with photographic portraiture. Calendars with photographs of everything from nude gringas to plumed Incas graced the walls of their houses. Newspapers, books, and magazines were treasured objects brought from Cusco or Lima. Some people had studio portraits of relatives or ancestors wrapped carefully in old scraps of textiles or tucked away in the niches of their homes’ adobe walls. Despite the diversity of the photographs they had seen, the poses they chose for their own portraits were remarkably uniform. They stood stiffly, with their arms down at the side, facing the camera, with serious faces. Photographs with smiles were usually rejected, as were the unposed, or what we would call “natural,” photographs I took on my own. My subjects were also committed to being photographed in their best clothes. I did a good deal of my interviews and other fieldwork while hanging around houses waiting for them to wash and braid their hair, scrub the baby, and even trim the horses mane in preparation for the family portrait. I began to develop a theory about their understanding of what portraits were and their attachment to particular poses. According to my field notes, it had something to do with the history of photography (about which I knew virtually nothing at the time) and the types of poses required for the very old cameras still used in Cusco’s public plazas and commercial studios.

As my curiosity about peasants and photographs grew, I began to experiment. I took books of photographs to the field to show people. I wanted to see how they judged the pictures. What would they say? I think I expected them to be either indifferent or disapproving. But their comments proved to be much more astute. One day while looking through Sebastiao Salgado’s Other Americas, for example, my friend Olga surprised me.1 I had chosen Salgado’s work to discuss with her, in part, because I found it to be a book with no easy answers. The photographs were lush, lavish, textured, undeniably beautiful. As prints, they were technically perfect. They appealed to everything I knew, consciously or unconsciously, about what a beautiful photograph was supposed to be. Yet as an anthropologist, I also found them alienating. They showed unhappy or destitute-looking people doing what appeared to be weird things. Where, I asked (somewhat self-righteously) were the people plowing fields, working in factories, or organizing strikes who also make up the “other Americas”?

Olga, however, found my concerns uninteresting. She liked the book a lot. Here were photographs that looked nothing like her own stiff-bodied portraits. Moreover, they were in black and white, a format that my “clients” systematically rejected. Nonetheless, this was her favorite among the several different books we had looked at. “Why?” I asked. “Because,” she said, “poverty is beautiful.” She proceeded to dissect several photographs for me. She liked how Salgado’s prints emphasized the texture of the peasants’ ratty clothes. She liked the fact that he showed an old peasant couple from the back, because this drew attention to the raggedness of their clothes (as well as, I thought, their anonymity). She even liked Salgado’s picture of cracked peasant feet—the one image on which my own negative opinion would not budge.

To this day, I’m not sure whether Olga convinced me with her praise for Other Americas. What she and her neighbors did do, however, was pique my curiosity about the ways in which visual images and visual technologies move across the boundaries that we often imagine as separating different cultures and classes. Clearly the peasants I photographed had their own ideas about photographs. These ideas shared much with my own. Yet they also differed in important ways. Olga’s comments about poverty and beauty—and my reaction to them—suggested to me the importance of reexamining my own assumptions about how political ideologies intersect with visual images. Similarly, our shared appreciation of the photographs’ formal qualities suggested something about the complex ways in which a European visual aesthetic had established its claims on our otherwise quite different ideas of the beautiful and the mundane.

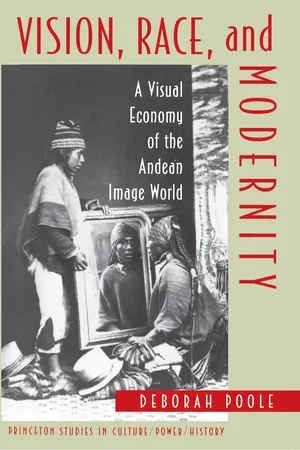

Although Olga and the other people with whom I lived, talked, and worked in the Cusco provinces of Paruro and Chumbivilcas during the early 1980s will appear nowhere in the pages that follow, this book is, in many ways, indebted to them. Their understanding of the power—and magic—of photography helped me frame my own interests in the history of visual technologies in non-European settings. Their attitudes toward the photographic image made me think about the political problem of representation in a slightly more critical way. Finally, my own experience as community retratista (portraitist) was constantly in my mind as I stared at thousands of mute images of Andean peasants held in the photographic archives of New York, Washington, Rochester, London, Paris, Lima, and Cusco. How would I decipher the intentions of the photographers who took these, sometimes anonymous, images? How could I even begin to imagine what the subjects of these nineteenth- and early twentieth-century photographs were thinking? How would I talk about and theorize the different visual styles I began to detect in European and Peruvian photographs? Where else beyond the archive should I look for insights into the cultural and racial discourses that animated these silent images? What role did these photographs in fact play in shaping the identities and imaginations of the people who posed for them? What message about my own, late twentieth-century ideas of photography and the self were they sending back to me from their unique viewpoint on the Andean past? (Figure 1.1).

This book is an attempt to answer some of these questions. It is, in one sense, a contribution to a history of image-making in the Andes. In another, much broader sense, it uses visual images as a means to rethink the representational politics, cultural dichotomies, and discursive boundaries at work in the encounter between Europeans and the postcolonial Andean world. In describing this encounter, I am particularly concerned with investigating the role played by visual images in the circulation of fantasies, ideas, and sentiments between Europe and the Andes. One goal of the book is to ask what role visual discourses and visual images played in the intellectual formations and aesthetic projects that took shape in and around the Andean countries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. A second goal is to examine the role of visual images in the structuring and reproduction of the scientific projects, cultural sentiments, and aesthetic dispositions that characterize modernity in general, and modern racial discourse in particular. The visual materials analyzed here include images from eighteenth-century novels and operas, engravings from nineteenth-century scientific expeditions, cartes de visite, anthropometric photography, costumbrista painting, Peruvian indigenista art, and Cusqueño studio photography from the 1910s and 1920s.

Figure 1.1. Girl with mirror (c. 1925)

As this list of image forms and genres makes clear, my purpose is neither to write a history of visual representation in the Andes nor to compile a comprehensive inventory of the motifs, styles, technologies, and individuals implicated in constructing “an image of the Andes.” The diversity, even unorthodoxy, of the images and image-objects that have circulated around and through the Andes dictates against any such singular histories. It calls instead for a consideration of the astounding number and variety of images and image-objects through which that place called “the Andes” has been both imagined and desired, marginalized and forgotten by people on both sides of the Atlantic.

The term “image world” captures the complexity and multiplicity of this realm of images that we might imagine circulating among Europe, North America, and Andean South America. With this term, I hope to stress the simultaneously material and social nature of both vision and representation. Seeing and representing are “material,” insofar as they constitute means of intervening in the world. We do not simply “see” what is there before us. Rather, the specific ways in which we see (and represent) the world determine how we act upon that world and, in so doing, create what that world is. It is here, as well, that the social nature of vision comes into play, since both the seemingly individual act of seeing and the more obviously social act of representing occur in historically specific networks of social relations. The art historian Griselda Pollock has argued, “the efficacy of representation relies on a ceaseless exchange with other representations.”2 It is a combination of these relationships of referral and exchange among images themselves, and the social and discursive relations connecting image-makers and consumers, that I think of as forming an “image world.”

The metaphor of an image world through which representations flow from place to place, person to person, culture to culture, and class to class also helps us to think more critically about the politics of representation. As I shall argue, the diversity of images and image-objects found in the Andean image world speaks against any simple relationship among representational technologies, surveillance, and power. Neither the peasants whose portraits I took, nor the many Peruvians with whom I later spoke while researching this book, nor the images I found in archives and books conformed to any simple political or class agendas. Nor were they immune to the seductions of ideology. Rather, like most of us, they seemed to occupy some more troublesome niche at the interstices of different ideological, political, and cultural positions. To understand the role of images in the construction of cultural and political hegemonies, it is necessary to abandon that theoretical discourse which sees “the gaze”—and hence the act of seeing—as a singular or one-sided instrument of domination and control. Instead, to explore the political uses of images—their relationship to power—I analyze the intricate and sometimes contradictory layering of relationships, attitudes, sentiments, and ambitions through which European and Andean peoples have invested images with meaning and value.

One way of thinking about the relationships and sentiments that give images their meaning is as a “visual culture.” Indeed, this might seem the obvious route for an anthropologist engaged in visual analysis. The term “culture,” however, brings with it a good deal of baggage.3 In both popular and anthropological usage, it carries a sense of the shared meanings and symbolic codes that can create communities of people. Although I would not want to dispense completely with the term visual culture, I have found the concept of a “visual economy” more useful for thinking about visual images as part of a comprehensive organization of people, ideas, and objects. In a general sense, the word “economy” suggests that the field of vision is organized in some systematic way. It also clearly suggests that this organization has as much to do with social relationships, inequality, and power as with shared meanings and community. In the more specific sense of a political economy, it also suggests that this organization bears some—not necessarily direct—relationship to the political and class structure of society as well as to the production and exchange of the material goods or commodities that form the life blood of modernity. Finally, the concept of visual economy allows us to think more clearly about the global—or at last trans-Atlantic—channels through which images (and discourses about images) have flowed between Europe and the Andes. It is relatively easy to imagine the people of Paris and Peru, for example, participating in the same “economy.” To imagine or speak of them as part of a shared “culture” is considerably more difficult. I use the word “economy” to frame my discussion of the Andean image world with the intention of capturing this sense of how visual images move across national and cultural boundaries.

The visual economy on which this book focuses was patterned around the production, circulation, consumption, and possession of images of the Andes and Andean peoples in the period running from roughly the mid-eighteenth to the early twentieth century. I have defined the chronological boundaries of this economy, on the one extreme, by the occurrence of certain shifts (about which I will have more to say in a moment) in the status of both vision and the observer in European epistemologies. On the other extreme, I have closed my inquiry in the decades preceding the advent of mass media and what Guy Debord has called the “society of the spectacle.” The changes wrought in our understanding of images and visual experience by television and cinema have been dramatic. This book considers the visual economy that anticipated these changes in visual technology, public culture, and the forms of state power they presumed.4

In analyzing this economy, my goal is twofold: On the one hand, I want to understand the specificity of the types of images through which Europe, and France in particular, imagined the Andes, and the role that Andean people played in the creation of those images.5 On the other hand, I am interested in understanding how the Andean image world participated in the formation of a modern visual economy. Two features in particular distinguished this visual economy from its Enlightenment and Renaissance predecessors. First, in the modern visual economy the domain of vision is organized around the continual production and circulation of interchangeable or serialized image objects and visual experiences. Second, the place of the human subject—or observer—is rearticulated to accommodate this highly mobile or fluid field of vision. These new concepts of observation, vision, and the visual image emerged toward the beginning of the nineteenth century at a time when Eur...