![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Hunters and Farmers: Early Prehistory

The fact that Anglesey is an island has been crucial to its history; and the same is true of Britain. When man first colonised this promontory of Europe more than half a million years ago he had moved north, and eventually even reached north Wales, on foot. But we now know that about 220,000 BC the link was broken by rising seas and that original population may have been trapped and gradually died out. New groups of ‘modern’ men and women re-colonised the region after the end of the last Ice Age and it is they who left the earliest evidence of human occupation in Anglesey, coming at a time just before the rocky landbridge at the Swellies was finally broken in about 7,000 BC.

That evidence is very slight, only scatters of chipped flints, the debris of shaping the tiny arrow tips which are all that survive from an array of wooden bows and arrows, osier fish traps and a variety of other hunting equipment with which they maintained a successful, mobile way of life which left only a light footprint upon the land. Where caves were available they sheltered in them and a few round huts have been found from this period, but archaeologists judge that the groups were small and moved frequently, following game in seasonal patterns. This was a way of life, with smoked salmon and oysters, not unlike that of nineteenth-century aristocrats, but without champagne.

For such a life the shore offered many resources, fish, shellfish and wildfowl, and most of the evidence of Mesolithic man in Anglesey has been found close to the present coast. One must remember, however, that the sea level has changed since 8–6,000 BC and campsites like those at Rhoscolyn and at Trwyn Du near Aberffraw would have overlooked a fringe of probably marshy lowland which is now submerged below the sea and may have contained other occupation sites now lost.

The change from a hunting to a farming economy which occurred in Britain in the centuries around 4,000 BC has been the subject of much debate. It represents a major change in attitudes and in most aspects of everyday life. The change in attitude is in many ways the more significant; man now sought to change and control nature, to modify plants and animals, not simply to use them. To do this land needed to be cleared and to be managed and thus, perhaps, owned and occupied more permanently. While growing crops and breeding animals had the potential to increase food supply and populations expanded, it also held the possibility of disaster. It is not surprising that at this time traditions of burial become more elaborate, resulting in long-lasting monuments which epitomise anxiety and the concern for family continuity guaranteed by the ancestors, venerated, perhaps even worshipped, in their great tombs.

The process by which this major change spread across Europe and into the islands of Britain and Ireland has never been clear and may have varied from place to place. Mesolithic hunters may have been moving towards animal control in some regions, but the appearance of new crops ultimately from the Near East and of sheep and goats with a similar background demonstrates that new settlers must have been involved. In Anglesey it is clear that new people and ideas were abroad in the Irish Sea area, for many elements of the new way of life are remarkably similar in Ireland and in western Wales. The island, with good harbours and fertile land, must have been a magnet for seafarers, probably in skin boats akin to the Irish curraigh, and the variety of tombs here suggests that groups with differing backgrounds were established from an early date.

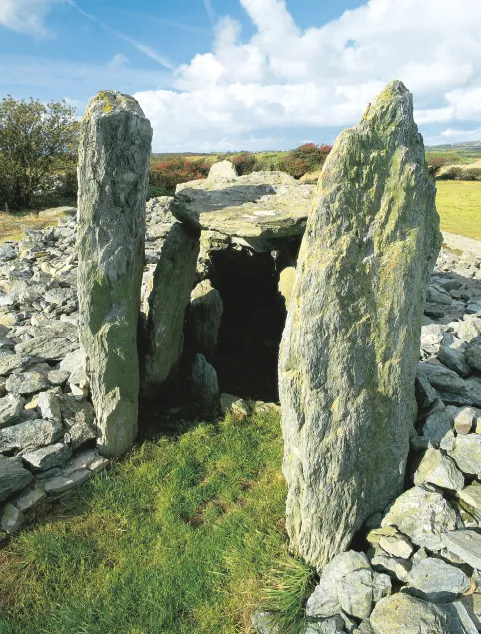

The tombs of the first farmers vary in design but all share an impressive monumentality and, where the evidence survives, contain the remains of several individuals, men, women and children, without any accompanying goods to indicate their status in life or their personal identity, beyond membership of an ancestral group. There are two main types of tomb; those with a box-like burial chamber and an impressive portal entrance and those where the burial chamber is separated from the outside world by a narrow passage. Both would have been covered by a mound or cairn of stones, in the first type usually rectangular and in the second normally round. The covering mounds seldom survive intact and the large stones forming the chambers are exposed. Some have been so damaged as to make the original plan impossible to reconstruct while others are difficult to classify because they combine elements from different traditions to make unique ‘hybrids’. In some instances, such as Trefignath near Holyhead, it can be shown that the monument was built in several stages over several hundred years. Most of the tombs were probably built during the Early Neolithic but they continued to be a focus for their communities for many centuries, even after active burial use had ceased.

These tombs, which are thought to be not only a burial place and shrine to the ancestors but also a symbol and guarantee of the continuity of the living community, are the oldest structures in our modern landscape, still performing that symbolic role after all trace of the everyday lives of their builders has vanished. The houses of the dead were permanent but the houses of the living were of wood and decayed.

Neolithic houses were big rectangular structures, not unlike medieval hall-houses, built for domestic life and storage and perhaps public hospitality. They are rarely found; areas of settlement are normally indicated by fragments of pottery, broken stone tools and a scatter of refuse pits. However the ground plan of a large wooden house has recently been found close to the stone tomb at Trefignath in an area where the history of vegetation preserved in the bogs demonstrates that trees had been cut to clear land for cultivation. Individual fields of this date have not been identified but large stone axes used to fell the natural woodland have been found in large numbers in most parts of the island. Many of them are made from stone from Penmaenmawr across the Straits, demonstrating a wide network of contacts and a sophisticated understanding of materials, for this stone is exceptionally sharp and hard.

Aberffraw Dunes and Trwyn Du B3

This view, looking across the sandy estuary of the River Ffraw, epitomises the changing nature of the coastline. The flat sands were once dry land for quite a considerable distance and the marron-covered dunes in the foreground are relatively modern and transient geographical features, while the rocky headland in the middle distance provides an element of permanence, though its levelled top is a product of glacial erosion. The striking profile of the Llŷn Peninsula in the background was created by more violent geological processes, for most of the peaks are extinct volcanoes.

There is extensive evidence of Mesolithic occupation on the headland of Trwyn Du where characteristic small flint tools, arrowheads, knife blades and scrapers, were first found when the Bronze Age cairn was excavated in 1956. The debris of this camp site extended beyond the area covered by the later cairn and in 1974 a larger area was excavated when over 5000 pieces of flint and chert were collected. Though no hearths or shelters were found, charcoal and hazel nut shells provided a radiocarbon date indicating that people were living and working here in the years around 8,000 BC. Looking at the site today one would imagine that sea food would have formed a large part of their diet, but at the time the sea would have been three or four miles away, though the river would have passed close by. Other finds of Mesolithic tools at sites under the village of Aberffraw reveal how attractive rivers were to hunters, shooting down wildfowl with bows and arrows and trapping game coming to the fresh water to drink.

The change in coastline and sea levels is manifest on the beach at Lligwy. What seem at first glance to be patches of mud and oil are in fact remnants of coastal peat beds formed thousands of years ago when the sea’s edge was much further out. In some areas the stumps of drowned trees can be seen, exposed by winter storms.

Trefignath Burial Chamber A2

Trefignath has seen a lot of changes since 1867 when W. O. Stanley painted this view: the monument has been excavated and re-interpreted; the background is now dominated by a large aluminium works and the farmland has been swept away by a new industrial park, whose excavation has added the site of a Neolithic house to the scene.

The tomb was saved from complete destruction in 1800 by Lady Stanley (W. O. Stanley’s mother) who, passing in her carriage, saw her tenant busily removing stones and put an immediate stop to the process. What remained were three groups of stones: a rectangular chamber with high entrance stones to the east, another with its broken capstone balanced against its backstone, and a heap of fallen slabs. The tall portal stones invited comparison with the court tombs of the north of Ireland and it was assumed that the chambers had formed a continuous gallery built as a single monument. Excavation in 1977 was prompted by the collapse of the central backstone and a very different history emerged.

Trefignath, view from the west

This view of the tomb from the west after excavation and restoration shows the initial chamber, which is interpreted as a Passage Grave opening to the north, with beyond that the backstone of the second, central chamber and its modest northern portal, and finally the most complete structure, the striking eastern chamber with its high portal stones and complete covered box-like burial space. Around the uprights of the chambers are the stones of the cairn whose survival within a dip in the rock was so surprising and so crucial to understanding the sequence in which the three chambers were built.

The status of the fallen stones at the west end was always uncertain and many thought them merely a pile of slabs abandoned by the farmer on the orders of Lady Stanley. The results of the excavation showed that they were the remains of a true chamber, collapsed but in situ. Moreover this had been the first monument to be built here. At a later date the simple rectangular central chamber was built to the east and that had a walled forecourt and a neatly edged cairn which covered the original structure but maintained access to it on the north side. Finally a similar rectangular chamber, but more flamboyant in its striking duplicated portal, was built hard against the forecourt of the central tomb and the walled cairn was extended to cover it. The point where the wall of the added cairn abuts the earlier one on the south side is the best field evidence for the multi-period construction of these monuments to be seen at any tomb in Britain.

The realisation that many tombs may be the product of a long period of building; that chambers of different styles may have been added to an original monument as ideas developed, or new ideas were adopted from other regions, newly contacted, has been an enormous relief to students of the period. Just as we expect churches and cathedrals to reflect differing architectural fashions and even different religious organisation, so we can now see the development of Neolithic tombs in the same way, but perhaps with less confidence about our understanding of the motives and theological content.

Trefignath, east chamber portal

The east chamber has a far more dramatic entrance portal than the central chamber. These tall stones may well have been spanned by a lintel stone now lost, just as all record of the b...