- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Margareta Ingrid Christian unpacks the ways in which, around 1900, art scholars, critics, and choreographers wrote about the artwork as an actual object in real time and space, surrounded and fluently connected to the viewer through the very air we breathe. Theorists such as Aby Warburg, Alois Riegl, Rainer Maria Rilke, and the choreographer Rudolf Laban drew on the science of their time to examine air as the material space surrounding an artwork, establishing its "milieu," "atmosphere," or "environment." Christian explores how the artwork's external space was seen to work as an aesthetic category in its own right, beginning with Rainer Maria Rilke's observation that Rodin's sculpture "exhales an atmosphere" and that Cezanne's colors create "a calm, silken air" that pervades the empty rooms where the paintings are exhibited.

Writers created an early theory of unbounded form that described what Christian calls an artwork's ecstasis or its ability to stray outside its limits and engender its own space. Objects viewed in this perspective complicate the now-fashionable discourse of empathy aesthetics, the attention to self-projecting subjects, and the idea of the modernist self-contained artwork. For example, Christian invites us to historicize the immersive spatial installations and "environments" that have arisen since the 1960s and to consider their origins in turn-of-the-twentieth-century aesthetics. Throughout this beautifully written work, Christian offers ways for us to rethink entrenched narratives of aesthetics and modernism and to revisit alternatives.

Writers created an early theory of unbounded form that described what Christian calls an artwork's ecstasis or its ability to stray outside its limits and engender its own space. Objects viewed in this perspective complicate the now-fashionable discourse of empathy aesthetics, the attention to self-projecting subjects, and the idea of the modernist self-contained artwork. For example, Christian invites us to historicize the immersive spatial installations and "environments" that have arisen since the 1960s and to consider their origins in turn-of-the-twentieth-century aesthetics. Throughout this beautifully written work, Christian offers ways for us to rethink entrenched narratives of aesthetics and modernism and to revisit alternatives.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Objects in Air by Margareta Ingrid Christian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

[ CHAPTER 1 ]

Aer, Aurae, Venti

Warburg’s Aerial Forms and Historical Milieus

Anima Fiorentina

In the autumn of 1900 the Dutch German art historian and literary scholar André Jolles wrote a letter to his friend Aby Warburg. In his letter Jolles announced that he had fallen in love. His object of affection was remarkable: she was born almost four hundred years before his time, between 1486 and 1490; she lived in a church in Florence; and she could fly. Jolles describes her wearing a windblown veil, floating as if on clouds, and hastening through the ether.1 The lady in question is the figure of the fruit-bearing girl depicted on Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco The Birth of Saint John the Baptist (1486–1490) (fig. 1.1) on the left wall of the Tornabuoni Chapel in the church Santa Maria Novella in Florence.2 She is unlike any other figure on the fresco: the billowing veil behind her recalls antique representations of aurai, ancient nymphs of the breezes (fig. 1.2).3 She is enveloped in a literal atmosphere; and she is excessively energetic. Jolles exclaims, “This is no way to enter a sick room, even if one wants to congratulate. This lively and light, yet highly animated way of walking; this energetic unstoppability, this length of step while all other figures have something untouchable, what is the meaning of all this? . . . Enough, I lost my heart to her. . . . Who is she? Where does she come from?”4

In his reply to Jolles, Warburg describes her as a “pagan play of winds” that whirls into Ghirlandaio’s picture of subdued Christianity. Her aerial animation is incongruous with her immediate environment: she is a pagan nymph in a Christian setting and a figure of antiquity in a Renaissance artwork. As an air dweller who is light footed, windswept, and excessively mobile, the nymph is at odds not only with her biblical environment and quattrocento milieu but also with her aesthetic medium. She is “the embodiment of movement” in an unmoving image.5

Figure 1.1. Domenico Ghirlandaio, The Birth of Saint John the Baptist, 1486–1490. Fresco (prerestoration). Tornabuoni Chapel, Florence. Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

Figure 1.2. Ara Pacis: The Fertile Earth. Museum of the Ara Pacis, Rome. Photo Credit: Scala / Art Resource, NY

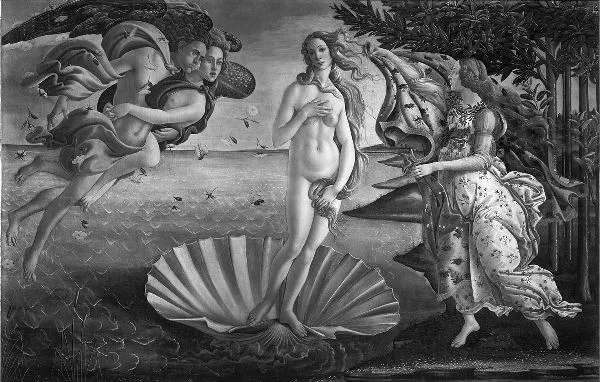

Figure 1.3. Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus. Ca. 1485. Tempera on canvas, 67.9 in × 109.6 in. Uffizi, Florence. Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY

Warburg regards the discrepancy between the atmosphere surrounding the nymph and the general setting of the fresco as indicative of anachronisms and contradictions inherent in Renaissance culture at large. On the one hand, the eruption of an ancient pagan past into quattrocento Christianity, and on the other, the outbreak of an illogical exuberance of movement in purportedly rational Renaissance art. Therefore, the incongruity between the aerial nymph and her surroundings points in fact to the artwork as a product of a similarly incongruent cultural milieu. Warburg examines the latter in terms of negotiations regarding the fresco between “church, merchant, artist”6—the Dominican monks of the church Santa Maria Novella; Giovanni Tornabuoni, merchant in Florence, and patron of the chapel; and Ghirlandaio, artistic executor, decorator of the chapel’s walls. In this sense the aerial nymph points Warburg to the fresco’s broader context: the Florentine cultural and social milieu at the end of the quattrocento.7 Warburg argues similarly in his dissertation: he connects the depictions of hair and clothes blowing in the wind to “inspirers” in Botticelli’s cultural environment. These inspirers—poets, learned scholars of the period—advised the painter on how to represent his figures, and their inspiration of Botticelli is evident in literally inspired representations: windblown hair and textiles (fig. 1.3). These aerial accessories become embodiments of the anima Fiorentina, of the cultural atmosphere in Florence.8

In this chapter I examine Warburg’s dissertation for the layers of meaning that are implicit in his word choice, that encapsulate his unarticulated arguments, and that have been overlooked in the history of his text’s reception. I specifically unravel the thematic undercurrent of air—a theme cloaked in semantic affinities and philological minutiae—by tracing each term that makes up the semantic field around air: Inspirator (inspirer), Stimmung (mood, atmosphere), Milieu (milieu), and Einfluss (influence). In all these words, Warburg activates their reference to a circumambient medium—in particular, air. I suggest that air represents, on the one hand, the physical medium in which Botticelli’s windblown accessories move and, on the other hand, the anima Fiorentina,9 the Florentine artistic and intellectual milieu, the cultural atmosphere in which Botticelli’s paintings are born. Air as the formal manifestation of an artist’s inspiration becomes air as the spatial expression of an artwork’s environment. However, air functions in the dissertation not only as a thematic strain but also as an implicit disciplinary trope for the cultural history into which Warburg aimed to extend all traditional art history.

Thus, I argue first that air figures the cultural medium in which artworks develop. Air points to the broadening of the analysis of an object into that of its milieu and its determining conditions. It points to the cultural-historical reframing of art history, which requires artworks to be studied in their environments through an examination of the economic, artistic, and anthropological conditions that determine them. Second, I show that the semantic field around air is the site of confluence for Warburg’s philological sensibilities and physiological interests. The motif of air crystallizes the entwinement of humanistic and scientific methodologies that helps construct Warburgian art history as cultural history.10 Third, I contend that as an element shared by different disciplines (such as philology and biology), air embodies the common medium that enables the actio ad distans between fields of inquiry, acting as a disciplinary milieu that permits semantic sympathies between words and fosters affinities between texts and images from distant epochs. Therefore, in Warburg’s dissertation, air also figures a method of writing that hinges on the conceptual mobility that enables cultural history and its analyses of itinerant aesthetic forms across times, spaces, and branches of knowledge.

This chapter analyzes unobtrusive terms that do not point to an immediate theoretical superstructure and then moves to the larger conceptual and cultural implications of this seemingly innocuous lexicon. The chapter enacts a method that combines philological attention with broad cultural and disciplinary concerns, including the formation of disciplines around 1900, ecological perspectives avant la lettre in the humanities, and the transfer of knowledge between the sciences and the humanities in the period. It shows how Warburg’s work can guide not only interdisciplinary work today but also intervene in recent methodological debates about the return to philology and the maintenance of larger cultural perspectives.

In the second half of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a growing trend toward understanding culture not as a series of symbolic human activities but as a collection of adaptive human mechanisms. The latter view regarded culture in evolutionary and biological terms:11 culture was the human environment, and cultural products were the result of human beings’ adapting to their surroundings. Warburg’s dissertation—with its conflation of air, environment, and culture—reveals a historical moment in which culture is increasingly viewed as an evolutionary-biological phenomenon. Culture is the quintessential human milieu. Furthermore, Warburg’s philological interest in influence—in the transmission of forms from antiquity to the Renaissance—goes hand in hand with an evolutionary-biological interest in the transfer of information. His dissertation, in which he traces cultural transfer across epochs, lays the foundations for his later work, conceived as an evolutionary study of European cultural history.12 It reveals not only that Warburg relied on philological and biological knowledge to construct his disciplinary approach but also that his later cultural-historical work goes back to a particular textual and visual practice and not an articulated theory. His dissertation shows the disciplinary extension of art history into cultural history in practice.

Inspiration

According to Plutarch, the priestess presiding over the Oracle of Apollo in the temple of Delphi, the Pythia, delivered her prophecies in a state of inspiration induced by sacred vapors. The priestess’s inspiration was literal: she inhaled air rising from the Castalian’s fragrant streams through a cleft in the ground. Plutarch’s Morals includes several discussions of the Pythia’s prophetic powers. In a conference with Demetrius and Philippus, Ammonius notes, “Just now in our discourse we have taken away divination from the Gods . . . and now we are . . . referring the cause, or rather the nature and essence, of divination to exhalations, winds, and vapors.”13

In his dissertation, Warburg shows how antiquity was a source of inspiration for early Italian Renaissance art. He resorts to the word Inspirator (inspirer) to describe the humanist scholars who channeled the diffuse influence of antiquity into concrete aesthetic advice. For instance, Angelo Poliziano was one of Botticelli’s “inspirers”: he advised the painter to choose antique forms of movement. Inspirieren, borrowed from the Latin inspirare (literally, to blow into), is a loanword in German. Warburg insists on this loanword and especially on its uncommon form Inspirator throughout the dissertation. This seemingly innocuous philological detail becomes remarkable in view of Warburg’s attention to depictions of breezes, zephyrs, and breaths in images and texts from antiquity and the quattrocento. In the context of so much air in motion, Inspirator suggests that the inspirer’s advice was translated into depictions of literally inspired objects—the windblown garments and windswept hair locks of Botticelli’s figures.

Aby Warburg argued for a cultural-historical opening up of the field of art history, rejecting the strict formalist analysis of artworks espoused by contemporaries such as Heinrich Wölfflin. He saw artworks as embedded in their historical contexts and art historians as agents who unravel an image’s cultural, social, anthropological, and political layerings. At the heart of his cultural history lies an iconology that defined the image worthy of inclusion in art history broadly. Warburg analyzed postage stamps alongside Albrecht Dürer’s paintings; he examined advertising art, pamphlets, and news photographs alongside ancient and medieval reliefs. His attention to low and high art from different epochs and regions coupled with his disciplinary extension of art history into cultural history make Warburg a founding father of Kulturwissenschaft (literally, culture science) and his scholarly work a precursor of cultural studies.14 Today, Warburg’s work, famous for its capaciousness, is invoked whenever interdisciplinary pursuits are at stake. As an art historian with a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- introduction Artworks and Their Modalities of Egress

- chapter 1 Aer, Aurae, Venti: Warburg’s Aerial Forms and Historical Milieus

- chapter 2 Luftraum: Riegl’s Vitalist Mesology of Form

- chapter 3 Saturated Forms: Rilke’s and Rodin’s Sculpture of Environment

- chapter 4 The “Kinesphere” and the Body’s Other Spatial Envelopes in Rudolf Laban’s Theory of Dance

- coda Space as Form

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index