eBook - ePub

Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society

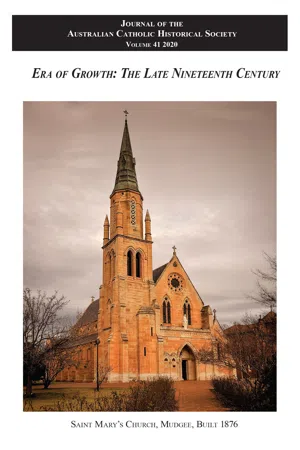

Era of Growth: The Late Nineteenth Century

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society

Era of Growth: The Late Nineteenth Century

About this book

This book uncovers the campaign aimed not only at personally destroying one of Australia's most influential religious leaders, but also of trashing the reputation of the Catholic Church. Had it succeeded, the campaign would have set damaging precedents for the rule of law in Australia. Pell spent 400 days in prison before a unanimous judgment of the High Court finally set him free. Those who have read transcripts of these proceedings will find their knowledge enriched by Windschuttle's book. For those who have relied only on the media for information about the saga of Pell, reading this book is a duty.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society by James Franklin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Theology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian TheologyFanaticism, Frisson, and fin de siècle France: Catholics, Conspiracy Theory, and Léo Taxil’s ‘Mystification’—Part 1

On November 21, 1907, the Sydney-based Catholic Press—a forerunner to the modern Catholic Weekly—published an anonymous (and probably syndicated) article entitled ‘The World’s Worst Liar’, subtitled ‘Gabriel Jogand and His Hoax’.1 This somewhat distasteful piece of post-mortem polemic gave a brief and highly selective account of the late nineteenth century ‘mystification’ of the erstwhile French anticlerical, expelled and disgraced Freemason, and later feigned convert to the Roman Church, Gabriel Jogand-Pagès (1854–1907). A figure better known to posterity by his nom de plume: Léo Taxil. The article, with some morbid satisfaction, held that Taxil had ‘died despised by those who had known him and by the great world he had cheated’. Among other pieces of invective, the Catholic Press article referred to Taxil as a ‘horrible buffoon’, whose ‘thrilling fairy tale under the guise of fact took the Catholic world by storm’. More accurately perhaps, however, it called him ‘the most successful fraud of the nineteenth century’—an appellation Taxil would have savoured.

To most Australian Catholics, both then and now, Taxil’s name was likely unfamiliar, but only a decade earlier he had made international headlines when he brought a dramatic conclusion to a twelve-year-long and highly lucrative literary masquerade which some American commentators called ‘the biggest hoax of modern times’.2

Playing on wider societal fears, Taxil almost single-handedly created a frisson in the French fin de siècle by convincing influential figures in the French (and wider European) Roman Catholic hierarchy and press of the existence of a vast and thoroughly fantastical conspiracy involving what he alleged were Satanic machinations taking place among the upper echelons of Freemasonry (what Taxil called ‘High-Masonry’)—in particular those of a fictional group he dubbed the Palladists.3

This article is the first instalment of a two-part historical examination of the ‘Taxil Hoax’, its historical background, and its reception. In this first instalment I will introduce the salient features of the hoax, highlight some important features of the French Third Republic (1870–1940) which made it conducive to conspiracist thinking, and give a very brief overview of recent historiography on the hoax. In the second instalment I will examine the very distinct initial reception within the Anglosphere—particularly amongst non-Catholic writers in Europe and America.

Taxil’s ‘Mystification’

In 1885 Léo Taxil renounced his earlier position as a notorious anticlerical journalist and publicist.4 Hitherto, Taxil had been responsible for a series of scurrilous and scandalous works aimed squarely at the clergy, with such memorable titles as Les Soutanes Grotesques (1879); Les Fils du Jesuite (1879–featuring an introduction by Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882); Les debauches d’un confesseur (1884–with Karl Milo); Les Pornographes sacrés: la confession et les confesseurs (1882); and Les Maîtresses du Pape (1884).5

At this time, Taxil feigned conversion to Catholicism, an event which achieved international media attention, and over a twelve-year period, beginning with an anti-Masonic work entitled Les frères trois-points (1885), began to cumulatively construct what would today be called a wild conspiracy theory about a fictional higher echelon group of Masons known as the Palladists.

Cashing in (quite literally6) on the anti-Masonic enthusiasm occasioned by Pope Leo XIII’s 1884 encyclical Humanum Genus,7 Taxil’s earliest post-conversion writings plagiarised numerous pre-existing texts and fabricated others, taking well-worn anti-Masonic tropes regarding alleged sexual deviancy and political intrigue and weaving these into an increasingly fantastical narrative in writings with titles like: Les Sœurs maçonnes (1886); Les Mystères de la franc-maçonnerie (1886); and La France maçonnique, liste alphabétique des francs-maçons, 16 000 noms dévoilés (1888)—the latter of which is, quite literally, an alphabetical list of members of the Grand Orient. These works, like Taxil’s earlier anticlerical writings, were one-part anti-Masonic propaganda, one-part plagiarism, and one-part scandal mongering. It was not until late 1891, however, in the wake of the success and controversy occasioned by Joris-Karl Huysman’s infamous Satanic novel Là-Bas earlier that year, that Taxil began to elaborate on his most diabolical creation: the Palladists.8

In Y a-t-il des femmes dans la franc-maçonnerie? (1891), an expanded version of his earlier Les Sœurs maçonnes, Taxil elaborated on the Palladists, who he had vaguely alluded to in the earlier text. Now referred to as the ‘New and Reformed Palladium,’ which (according to Taxil) had been formed in America in 1870, Taxil waxed lyrical about the Palladists’ alleged worship of Lucifer and their blasphemous rites.

These so-called Palladists, Taxil later claimed, controlled a worldwide Satanic cult from their headquarters in Charleston, South Carolina, initially under the leadership of Albert Pike (1809–1891)—a former Confederate General and high-level Scottish Rite Mason who had publicly denounced Pope Leo XIII’s anti-Masonic encyclical Humanum Genus in 1884,9 in a pamphlet.

In order to create a veneer of authenticity—certainly enough to convince many credulous clerics—Taxil also included numerous other well-known figures as dramatis personae. Among these were well-known anticlerical Freemasons like the Italian banker Adriano Lemmi (1822–1906) and figures connected with the fringes of masonry and the occult revival like John Yarker (1833–1913) and Dr William Wynn Westcott (1848–1925)—the latter two of whom were less than impressed when informed about their alleged involvement with the Palladists.10 In addition to this, Taxil created a series of characters out of whole cloth, notably the dreaded sapphic Templar mistress Sophie Walder, who Taxil described as ‘an incarnate she-devil, wallowing in sacrilege, a true Satanist, such as one meets in Huysmans’ books’.11

Over the next four years much more would be written about these alleged Palladists and particularly the (possibly fictitious) professed apostate from the Luciferic cult, Dianna Vaughan, who became the belle de jour of anti-Masonic writers. As time passed, however, the claims made about the Palladists became increasingly unbelievable.

With the assistance of his co-conspirator, a merchant surgeon named Dr Karl Hacks (alias Dr Bataille), the unwitting Italian dupe Domenico Margiotta, and the mysterious alleged Franco-American type-writer saleswoman Dianna Vaughan, between 1892 and 1895 Taxil produced, among other works, a monumental near 2000-page serialised work entitled Le diable au XIXème siècle. This adventure story, compared by some to the writings of Jules Verne,12 convinced all manner of credulous Roman Catholic anti-Masons not only of the existence of the Palladists, but also that since the final loss of the Papal States in 1870 this group had been working piecemeal to destroy the Church and ferment revolutions across Europe. Unsurprisingly, and importantly, Taxil found ready allies here, not least amongst reactionary anti-Masonic and antisemitic clerics like Monsignor Leo Meurin SJ (1825–1895), then Archbishop of Port Louis (Mauritius) and author of La franc-maçonnerie, synagogue de Satan (1893) and Monsignor Armand-Joseph Fava (1826–1899), then Bishop of Grenoble and editor of the anti-Masonic periodical La Franc-Maçonnerie démasquée published from 1884.13

It was at this point, according to Taxil’s confession, that things moved from relatively standard anti-Masonic tropes into the more absurd and clearly both Taxil and his collaborators were testing how far they could push the envelope. Le diable au XIXème siècle included, among its more sensational elements, Dr Bataille’s alleged visit to Sri Lanka in which he encountered Satanists who had a monkey that spoke Tamil and a spiritualist séance in which the pagan god Moloch was invoked and appeared in the form of a crocodile who proceeded to play a piano and drink the house dry! While some more sensible Roman Catholics cottoned onto the dubious nature of these claims, Taxil and particularly the mysterious Dianna Vaughan, continued to elicit great support amongst European clerics and religious who perceived in their writings proof positive of both the Masonic threat suggested in a series of papal encyclicals going back to Clement XII’s In Eminenti (1738), and moreover, of the fundamentally ‘Satanic’ nature of Masonic rites.14 As Taxil’s confession noted, he received ‘the most encouraging episcopal congratulations’ adding ‘not counting those of the grave theologians who didn’t bat an eyelid when our crocodile played piano’.15 While many of Taxil’s clerical supporters, one of whom sent him a gift of particularly expensive gruyere cheese from Switzerland, were clearly unsophisticated and pious dupes, others were far more culpable in swallowing the charade, including, according to ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Edmund Campion, Bicentenary of our First Official Priests: Fr Philip Conolly and Fr John Joseph Therry

- Colin Fowler, ‘Firebrand Friar’—Patrick Fidelis Kavanagh OSF (1838–1918)

- Tess Ransom, Fr Julian, Southport, and the Kennedy/Ransom Family—their Story

- James McDonald, Breadalbane, Ben Hall, and the Spurious Case Against Thomas Lodge

- Graham Lupp, Edward Gell, The Catholic Architect

- Paul Collins, The First Vatican Council (1869–1870)

- Robert Gascoigne, On the 150th Anniversary of the First Vatican Council and the Document Pastor Aeternus

- Tim O’Sullivan, Father George Tuckwell: Missionary Priest in the Australasian Colonies

- Bernard Doherty, Fanaticism, Frisson, and fin de siècle France: Catholics, Conspiracy Theory, and Léo Taxil’s ‘Mystification’—Part 1

- Margaret Carmody and Anne Marks, ‘Spontaneous to Help Where a Need Called’—The Life of Mrs JJ Clark

- Ann-Maree Whitaker John Sheehy: ‘An Irishman and a Sterling Catholic’

- Benjamin Wilkie, A Higher Loyalty? A Case Study of Anti-Catholicism and Section 44 of the Australian Constitution

- Stephen McInerney, Les Murray’s Sacramental Poetics

- Paul Crittenden, David Coffey: Theologian of Spirit

- Ron Perry, Bryan Gray and Alison Turner, Celebrating a Quiet Revolution: A Practical Response to Vatican 2: Celebrating the Life and Achievements of the Institute of Counselling—Archdiocese of Sydney

- Vivienne Keely, Michael Hayes: Life of a 1798 Wexford Rebel in Sydney, and Dixon of Botany Bay: The Convict Priest of Wexford, reviewed by Michael Sternbeck

- Anne Benjamin et al, Australian Catholic Educators 1820–2020, reviewed by Michael Bezzina

- Katharine Massam, A Bridge Between: Spanish Benedictine Missionary Women in Australia, reviewed by Kym Harris

- Chris Hanlon, The Catholic Church in Colonial Queensland, 1859–1918, reviewed by John Carmody

- Stephen Jackson, Religious Education and the Anglo-World: The Impact of Empire, Britishness, and Decolonisation in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, reviewed by Jeff Kildea

- Colin Barr, The Irish Ecclesiastical Empire, reviewed by Jeff Kildea

- Elisabeth Edwards, Wearing the Green: The Daltons and the Irish Cause, reviewed by Jeff Kildea

- Richard Reid, Jeff Kildea and Perry McIntyre, To Foster an Irish Spirit: The Irish National Association of Australasia 1915–2005, reviewed by Chris Geraghty

- Anne Henderson, Federation’s Man of Letters, reviewed by Tony Abbott

- Val Noone, Dorothy Day in Australia, reviewed by Michael Costigan

- Justin Darlow, Consider the Crows, Centenary of the Catholic Diocese of Wagga Wagga, 1917–2017: General Diocesan History, reviewed by Anthony Robbie

- Peter Malone, Screen Priests, Depictions of Catholic Priests in Cinema, 1900–1918, reviewed by Richard Leonard

- Peter Malone, Dear Movies, reviewed by Richard Leonard

- Wanda Skowronksa, Paul Stenhouse MSC: A Life of Rare Wisdom, Compassion and Inspiration and Peter Malone, editor, Paul Stenhouse: A Distinctive and Distinguished Missionary of the Sacred Heart, reviewed by Irene Franklin

- Nick Dyrenfurth and Misha Zelinsky, editors The Write Stuff: Voices of Unity on Labor’s Future, reviewed by David Cragg

- Bryan Turner and Damien Freeman, editors Faith’s Place: Democracy in a Religious World, reviewed by Michael Easson

- Keith Windschuttle, The Persecution of George Pell, reviewed by Damian Grace

- George Pell, Prison Journal Volume One: The Cardinal Makes His Appeal, reviewed by Edmund Campion