eBook - ePub

Standing at the Threshold

Working through Liminality in the Composition and Rhetoric TAship

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Standing at the Threshold

Working through Liminality in the Composition and Rhetoric TAship

About this book

Standing at the Threshold articulates identity and role dissonances experienced by composition and rhetoric teaching assistants and reimagines the TAship within a larger professional development process. Current researchers and scholars have not fully explored the liminality of the profession's traditional path to credentialing. This collection reconsiders these positions and their contributions to academic careers.

These authors enrich the TA experience by supporting agency and self-efficacy, encouraging TAs to take active roles in understanding their positions and making the most of that experience. Many chapters are written by current or former TAs who are writing as a means of preparing, informing, and guiding new rhet/comp TAs, encouraging them to make choices about how they want to think through and participate in their teaching work.

The first work on the market to delve deeply into the TAship itself and what it means for the larger discipline, Standing at the Threshold provides a rich new theorizing based in the real experiences and liminalities of teaching assistants in composition and rhetoric, approached from a productive array of perspectives.

Contributors: Lew Caccia, Lillian Campbell, Rachel Donegan, Jaclyn Fiscus-Cannady, Jennifer K. Johnson, Ronda Leathers Dively, Faith Matzker, Jessica Restaino, Elizabeth Saur, Megan Schoettler, Kylee Thacker Maurer

These authors enrich the TA experience by supporting agency and self-efficacy, encouraging TAs to take active roles in understanding their positions and making the most of that experience. Many chapters are written by current or former TAs who are writing as a means of preparing, informing, and guiding new rhet/comp TAs, encouraging them to make choices about how they want to think through and participate in their teaching work.

The first work on the market to delve deeply into the TAship itself and what it means for the larger discipline, Standing at the Threshold provides a rich new theorizing based in the real experiences and liminalities of teaching assistants in composition and rhetoric, approached from a productive array of perspectives.

Contributors: Lew Caccia, Lillian Campbell, Rachel Donegan, Jaclyn Fiscus-Cannady, Jennifer K. Johnson, Ronda Leathers Dively, Faith Matzker, Jessica Restaino, Elizabeth Saur, Megan Schoettler, Kylee Thacker Maurer

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Standing at the Threshold by William J. Macauley, Leslie R. Anglesey, Brady Edwards, Kathryn M. Lambrecht, Phillip Lovas, William J. Macauley,Leslie R. Anglesey,Brady Edwards,Kathryn M. Lambrecht,Phillip Lovas,William J. Macauley, Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Imitation, Innovation, and the Training of TAs

Lew Caccia

In my experience, I have noticed many TAs bring to the composition courses they teach a definite sense of how to succeed as a writer.1 For these TAs, the strategies for effective writing are specific to the environment. It seems TAs transfer their prior expectations as students and stress approaches toward product and process for which they have been affirmed. I have observed some TAs recall their preference toward immediate benefit, or “payback,” for an in-class exercise or assignment spread over at least two class meetings.2 Other TAs sometimes note their discomfort with assignments or activities perceived as having too many restricting requirements. Less evident is the rhetorical practice that can help enact pedagogical theory and facilitate dominant academic writing practices: imitatio.

Conversations about imitation are rare in pedagogy today. Perhaps this lack is expected given the dialectic that has existed between imitation and innovation in classical rhetoric and contemporary composition studies. Kathleen Vandenberg observes the studies as “concerned more with the relationship between composition students (as imitators) and teachers (as models) insofar as those relationships have potentially been sites of power, authority, resistance, and ‘violence’ (albeit not physical)” (2011, 112). Drawing from the perspective of social science philosopher Rene Girard, who believed that human development and rivalry are based on “mimetic desire,” Vandenberg affirms the eighteenth century as an approximate chronological divide. Heretofore, the basis for theoretical and applied logic was primarily theological, thus favoring imitation as an educational and professional practice. During the eighteenth century, the ascendancy of science and technology gave rise to logic that favored innovation. Since then, imitation and innovation have existed in tension linked with the binary dissociations of product and process, form and content, originality and correctness. Teachers have hesitated to use imitation because, for many, it connotes strict verbatim transfer and inhibits personal expression.

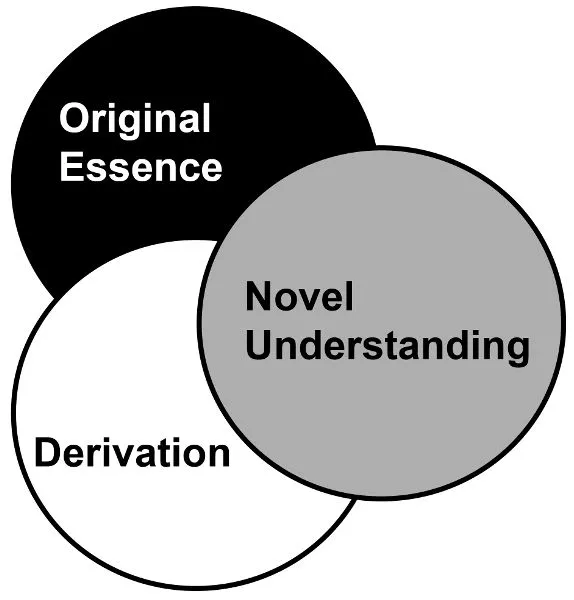

Responding to Vandenberg’s call to “illuminate debates over imitation pedagogy in composition studies” (2011, 112) in ways that inform teaching approaches and their relationship with classical rhetoric, this article envisions locating imitation at the forefront of writing-pedagogy education and explores the bases for doing so. Specifically, by drawing on classical rhetoric and contemporary representations of mimetic models, I explore how those engaged in TA training could productively use imitation to complement TAs’ prior academic success and their already substantive professional experience in nonacademic settings or prior teaching experience in secondary or alternative postsecondary environments. While a mastery of content—and the ability to ascribe the method by which the content is generated or executed—is essential to reproduce the style, tone, and rhetorical purpose demonstrated in pedagogical practice, informed imitation also integrates multiple models properly selected for emulation. As this essay explains in more detail, attention to pedagogy as imitative practice foregrounds mimesis as a new alteration by which a level of resemblance exists between the original essence and the derivation from which a novel understanding can emerge (figure 1.1). The degree of resemblance can vary among derivations, and the process of emulative selection can be a source of difficulty for imitators. Cicero speaks of such difficulty in De Oratore, acknowledging imitation as an affordance that preserves precision. Navigating the constraints posed by both imitative and inventive practice, Cicero recommends “using the best words—and yet quite familiar ones—but also coining by analogy certain words such as would be new to our people, provided only they were appropriate” (1967, 1.34.155).

Figure 1.1. Mimesis as new alteration

In this generative performance, Cicero enjoys the availability of choice while entertaining the responsibility of freedom. As Cicero found among the best words both the quite familiar ones and those that are appropriately coined, Quintilian too recognized the limited scope, even the contextual impossibility, of extended verbatim transfer. Regarding one case, Quintilian explains, “We simply cannot help contriving many of [the best possible words], and of various kinds, because Latin idiom is often different from Greek” (2001, X.v.3). The case put forth by Quintilian requires an adequate resemblance between the original and the translation. While the imitator enjoys the choice of new words and figures of speech, the imitator still bears the responsibility to retain the original meaning. When effectively executed, the resulting imitation coexists with the original essence, neither superior nor inferior but complementary in a way that advances new knowledge or awareness appropriate to the context of original goals and outcomes.

Understanding imitation as an essential pedagogical method also plays a valuable role for its link with technological and evolutionary progress. Philosophical conceptions of reality are defined by the embedded quality of rhetoric within the larger discursive and material contexts of human activity: “If our art is embryonic when compared with that of the future, then the art of the past must be even more undeveloped” (Sullivan 1989, 16). Thus, by connecting the technological mindset with faith in evolutionary progress, new insights emerge only if original forms and past practice are brought to continual, collective awareness. Communicative art, then, exists as a point of analysis and contemplation: “It tries to break up and challenge experience, make us put it back together in different ways” (Lanham 1976, 114). A careful reading of these passages intensifies our awareness that we cannot produce new insights without returning to the past, so we shouldn’t just ignore the past. This is not to say anyone is arguing that we should ignore the past, but this point is important because a general understanding of evolution (both as change and as stability) is premised on the operations of imitation. Hence, this is one of the many ways imitation should be acknowledged to TAs as essential to our thinking.

The imitative practice, or lack thereof, demonstrated by TAs is a concern in the scholarship of writing-pedagogy education. E. Shelley Reid (2011) notes liminality between the TAs’ writing-pedagogy education and their actual teaching practice. This liminality, which is discussed later in this essay, inhibits formalized mentoring goals and clarity on principled teaching, accounts of teaching challenges, and approaches toward those challenges. Despite the liminality, first-year TAs do typically express an implicit sense of imitatio in their expressed desire to enact the knowledge of their faculty mentors and practicum coordinators. For example, some of my TAs have noted in their journals for practicum the method by which their mentor distributes materials to students in the first-year composition class. They note positioning: where the mentor sits, stands, moves to another part of the room. Positioning is also accounted for in the figurative sense, how topical units are sequenced, how lessons are transitioned into one another. From a content perspective, journals note the manner by which lessons are partitioned. For example, one mentee described a class-long lesson on personification that began with definitions and descriptions of objective and subjective writing. TAs also contemplate in terms of differential imitation when questioning whether to cater teaching styles to particular students. They consider imitation in terms of limitation, whether they, for instance, agree with putting as many restrictions into an essay assignment. Mentees just as much consider imitation in terms of delineation, such as whether specific instructional practices can transfer from composition 101 to developmental English or perhaps to composition 102. TAs even consider the intangible or seemingly intangible issues of emotionally intelligent pedagogical practice, issues that include the question of how they too can build a type of relaxed, yet firm, relationship with students. In their own words, first-year TAs clearly desire to learn and build upon their existing expertise.

Because many new TAs draw more closely on their own experiences as students (or those of peers) than they do scholarship or direct mentoring—and because they are thirsty for models—working from that perspective by encouraging thoughtful imitation can be a way to help new teachers develop.

This encouragement should provide methods by which they could learn to engage and critique—in the service of understanding and enacting—instructional paradigms that contribute to dominant academic writing practices. Without a proper theoretical and applied logic, TAs are situated at a hindrance. Similar to the way they were asked to mimic the essential qualities of academic discourse in first-year composition, we should likewise instruct them to model generative tools and disciplinary vocabulary in first-year teaching. This more thorough rhetorical grounding would provide a means by which TAs take true ownership of pedagogical principles rather than simply perform educational approaches consistent with the programmatic goals, outcomes, and rubrics that inform assessment. As this essay establishes, an appreciation for emulative selection enables speakers and audiences to perceive more acutely the variable quality of repetitive sequence and its role in unconscious workings of evolutionary progress. If discovery is the process by which we advance knowledge, then affording TAs the resources to comprehend the innovative facets of classroom practice through imitative study of their and others’ teaching must not be an implicit agenda but an essential, reinforced component of writing-pedagogy education.

Defining Emulative Selection

As suggested above, one way to construct this grounding within the TA curriculum is through a study of emulative selection, a neglected facet of the larger scope of imitation. I contend that by initiating rhetorical practice into the practicum classroom and thereby accentuating imitation rather than performance, we can move TAs’ attention away from extended verbatim transfer and toward the more inventive yet equally complicated aspects. Figure 1.2 offers a mini wordle to help represent some of the imitable discourse processes that can be traced back to antiquity.

Figure 1.2. Several types of imitable discourse processes

Emulative selection could be defined as striving to excel, especially through imitation, by careful choice or representation. A central category among imitable discourse processes, emulative selection has been described in various ways. As Dale Sullivan explains in “Attitudes toward Imitation: Classical Culture and the Modern Temper,” several types of imitable discourse processes can be traced to De Oratore and Institutio Oratoria, including “very close imitative exercises like memorizing, translating, and paraphrasing, to rather loose forms of imitation: modeling and reading” (1989, 13). Imitation is generally and vaguely opposed to innovation and/or expression. This opposition, however, was not the case for the rhetorical tradition. In De Oratore, Cicero expands on the point of modeling as he offers an early pedagogical perspective, suggesting “that we show the student whom to copy, and to copy in such a way as to strive with all possible care to attain the most excellent qualities of the model” (1967, 2.22.90). Differentiating from the most excellent qualities of the model, Cicero offers an early version of imitation as generative work as opposed to repetitive labor, suggesting that “whereby in copying he may reproduce the pattern of his choice and not portray him as time and again I have known many copyists do, who in copying hunt after such characteristics as are easily copied or even abnormal and possibly faulty” (2.22.90). In this account, Cicero claims one can both imitate and critique any given model. Or more prescriptively, Cicero argues that imitation should be selective or it risks imitating faulty qualities. Exploring imitation as generative work thus brings an intentionality to imitation we don’t—at least in its simplest definition—give it.

Quintilian’s fundamental treatment of imitative practice in Institutio Oratoria can be applied across communicative forms and purposes. His efforts to incorporate rhetoric into a comprehensive curriculum offer insights that reinforce and extend Cicero’s pedagogical awareness. Following Cicero’s suggestion to show students whom to copy, Quintilian affirms it is from “authors worthy of our study that we must draw our stock of words, the variety of our figures and our methods of composition, while we must form our minds on the model of every excellence” (2001, 10.2.1). Quintilian complicates imitative practice on several levels, advising students to assume a critical perspective in their approach. One complication put forth by Quintilian is the inseparability of the intrinsic power of language from the effect of the speaker delivering the language. Quintilian goes as far as to assert that “the greatest qualities of the orator are beyond all imitation” (10.2.12). For the purpose of advising caution in the selection of emulative models, Quintilian attributes “talent, invention, force, facility, and all the qualities which are independent of art” as contributing toward the rhetorical force of discourse.

In addition to encouraging students to take a critical stance in selecting whom and what words to imitate (2001, 10.2.14), Quintilian also calls for integrating multiple models, drawing from not only one author or text or style but doing so in a way that coordinates with the students’ own talents and purposes. Quintilian thus presents us with an opportunity to develop theories of TAship in rhetoric and composition toward understanding the fullness of liminalities in those positions. TAs do not always enjoy the same social circumstances and power relations as their faculty. Foley-Schramm et al. offer as a case in point the “complex relationships and power dynamics embedded” (2018, 93) in their contributions toward a university-wide writing rubric. Later in this volume, Rachel Donegan offers another case of complex social circumstances and power relations in her description of a graduate student who had difficulty availing herself of the benefits of her official student accommodations. It is sometimes from their own specialized fields of expertise that TAs can attain legitimated authority from their audiences. Maintaining that even the most celebrated authorities have deficiencies subject to corrective evaluation by appointed critics and peers alike, Quintilian expresses his “wish that imitators were more likely to improve on the good things than to exaggerate the blemishes of the authors whom they seek to copy” (2001, 10.2.15). In his comprehensive treatment of rhetorical education, Quintilian thus establishes that not only can students imitate with alteration, they must imitate with alteration. By considering how imitation might be an act done deliberately and carefully, we can help new teachers attempt to use rhetoric as a lens to reconsider teaching practices.

As a form of critical engagement, emulative selection may not easily register among...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Rhetoric and Composition TA Observed, Observing, Observer

- 1. Imitation, Innovation, and the Training of TAs

- 2. Multimodal Analysis and the Composition TAship: Exploring Embodied Teaching in the Writing Classroom

- 3. Disciplinarity, Enculturation, and Teaching Identities: How Composition and Literature TAs Respond to TA Training

- 4. The Graduate Teaching Assistant as Assistant WPA: Navigating the Hazards of Liminal Terrain between the Role of Student and the Role of Authority Figure

- 5. The Invisible TA: Disclosure, Liminality, and Repositioning Disability within TA Programs

- 6. From Imposter to “Double Agent”: Leveraging Liminality as Expertise

- 7. Beyond “Good Teacher” / “Bad Teacher”: Generative Self-Efficacy and the Composition and Rhetoric TAship

- Afterword: Staying with the Middle

- About the Authors

- Index