1Gay Tourism: New Perspectives

Oscar Vorobjovas-Pinta

Defining Gay Tourism

Gay tourism is a dynamic and vibrant phenomenon. The definition of gay tourism is rather complex; however, it is generally described as a form of niche tourism that refers to the development and marketing of tourism products and services to lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning, intersex and other people (LGBTQI+). Although the term ‘gay’ technically refers to gay men and lesbians, it can also be used in a wider sense to include all other sexual orientations or gender identities under the LGBTQI+ banner. Therefore, the term ‘gay tourism’ in this book is used loosely and encompasses all forms and combinations of the LGBTQI+ acronym. Indeed, ‘gay tourism’ has been established as a more recognisable and user-friendly term than ‘LGBTQI+ tourism’ or any other derivations (Southall & Fallon, 2011).

The origins of gay tourism are commonly dated back to the era of the Grand Tour or perhaps even earlier (Aldrich, 1993). The Grand Tour involved wealthy, well-educated and upper-class gay men from Northern European countries travelling to the Mediterranean in search of exotic cultures, warmer climes and the companionship of like-minded men. Such travel was often associated with an artistic and aesthetic experience (Graham, 2002). Gay tourism flourished in the Victorian period (Aldrich, 1993; Clift & Forrest, 1999; Clift & Wilkins, 1995; Clift et al., 2002; Holcomb & Luongo, 1996). In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Berlin, Paris and London boasted sizeable gay leisure ‘infrastructure’, including cafés, cabarets, salons and bathhouses (Hughes, 2006; Peñaloza, 1996; Prickett, 2011). Indeed, Weimar Berlin was considered to be a ‘gay mecca’ or the ‘Eldorado’ of the times, offering a safe haven for locals and travellers alike (Clift et al., 2002; Prickett, 2011). One could escape the heteronormative social world and express one’s sexuality in a judgement-free space. Due to its tolerance, modernity and inclusive culture, Berlin remained a sanctuary for gay men and women until the Nazi revolution in 1933.

The manifestation of gay culture was not exclusively a European phenomenon. In the later years of the 19th century, New York became known for its numerous bathhouses, brothels and saloons which catered exclusively to gay clientele (Branchik, 2002; Graham, 2002). In 1877, the guidebook Pictures of New York Life and Character allegedly contained ‘gay’ content (Clift et al., 2002). New York’s famous bars such as The Slide, Webster Hall and Rockland Palace from the 1890s to the 1930s were part of a flourishing, highly visible LGBTQI+ nightlife and culture which would be integrated into mainstream American life in a way that would be unacceptable just 10–20 years later.

The gay tourism industry has experienced growth since the 1970s. While industry players stand to gain economically from becoming more inclusive, the social implications of such a shift remain critical. Gay tourism is not merely about sexual preference – it plays an integral role in one’s self-identification and self-expression. The literature has structured gay tourism into three distinct clusters: identity expression and exploration (Browne & Bakshi, 2011; Hughes, 1997); sense of community and fellowship (Hindle, 1994; Pritchard et al., 2000); and sexual candour (Clift & Forrest, 1999; Hughes, 2006). Therefore, gay tourism is often presented as an idealised escape from the heteronormative strictures of everyday life, and an opportunity to embrace and express one’s identity (Vorobjovas-Pinta, 2018). The thirst for escapism has encouraged the establishment of gay spaces, ranging from gay bars and nightclubs in urban environments to the exclusively gay travel resorts and destinations. This phenomenon even extends to gay townships and communities, such as Cherry Grove and Fire Island Pines on New York’s Fire Island. Previous studies emphasised the provision of gay space as the primary motivator encouraging the growth of gay travel (Vorobjovas-Pinta, 2018).

Gay tourism and leisure scholars have investigated the interlinked nature of one’s sexuality and the space in which it is performed (Binnie & Valentine, 1999; Caluya, 2008; Hughes, 2006; Waitt & Markwell, 2006). Vorobjovas-Pinta (2018) explains:

Space becomes a vessel for the ideologies, need, practices, and desires of those occupying it, and through this relationship the sexual, racial, and gender categories of its inhabitants become refracted in its imperceptible boundaries. (Vorobjovas-Pinta, 2018: 3)

LGBTQI+ and Societal Change

Historically, a breakthrough in the gay and lesbian movement occurred in the mid-20th century. An assemblage of several historic events and developments led to the liberation and acceptance of LGBTQI+ communities, including: the Stonewell Riots in 1969; a shifting of the demographic composition of the population; changes in cultural ideologies; increased educational levels; and the establishment of LGBTQI+ NGOs and university queer societies (D’Emilio, 1983; Loftus, 2001; Valocchi, 2005; Werum & Winders, 2001). In 1973, the American Psychiatric Association declassified homosexuality as a mental abnormality vis-à-vis a ‘sociopathic personality disturbance’ (Morin, 1977; Werum & Winders, 2001). In addition, in 1990 the World Health Organisation removed homosexuality from the list of mental illnesses known as the International Classification of Diseases (King, 2003). These changes paved the way for greater societal acceptance of LGBTQI+ communities, at least in the Global North. The attitudes towards LGBTQI+ individuals considerably differ depending on locality, culture, political climates, history and religion. Countries in the Global North adopted proactive legislative standards to become more inclusive (e.g. marriage equality, the right to adopt for same-sex couples), whereas many African, Asian and Eastern European countries are bounded by social and/or legal norms, which are reflected through the legal discrimination of LGBTQI+ people via prosecution and even the death penalty.

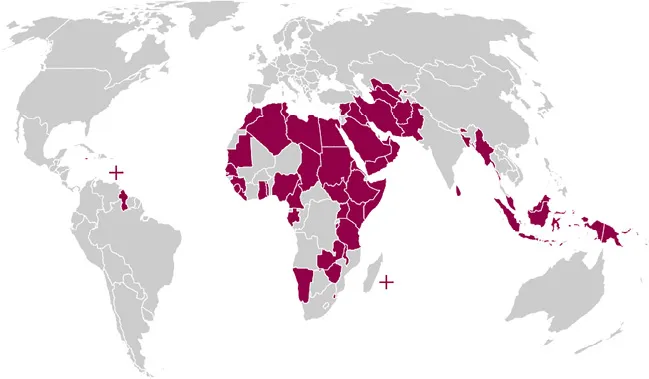

Despite homosexuality being de-pathologised in 1990, LGBTQI+ people are still criminalised in 73 jurisdictions across the world (see Figure 1.1). In 12 jurisdictions the death penalty is imposed or at least is a possible punishment for private, consensual same-sex sexual activity. At least six of these countries actually carry out the death penalty – Iran, Northern Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen – and the death penalty is a legal possibility in Afghanistan, Brunei, Mauritania, Pakistan, Qatar and UAE (Human Dignity Trust, 2020). Even in countries with generally tolerant societies, a degree of prejudice still exists within specific areas based on sociodemographic composition and geographic rurality (Ong et al., 2020).

Figure 1.1 Map of countries that criminalise LGBTQI+ people

Source: Human Dignity Trust (2020).

A Demographic Profile of LGBTQI+ Tourists

Gay tourists have often been characterised as high-yield travellers with significantly more disposable income than their heterosexual counterparts (Hughes, 2003). This has been largely attributed to the notion of gays and lesbians being DINKs (i.e. double income, no kids). Indeed, epithets such as a ‘dream market’ or an ‘untapped gold mine’ were used to define the gay market (Kahan & Mulryan, 1995; Peñaloza, 1996). This has led to claims that they represent a powerful, profitable and recession-proof market segment (Guaracino, 2007; Melián-González et al., 2011). It is estimated that the annual value of total spending on travel and tourism by LGBTQI+ people exceeds US$218 billion (Out Now, 2018). Gay travellers have also been lauded as trendsetters (Gluckman & Reed, 1997; Guaracino, 2007; Hughes, 2005) and innovators (Vandecasteele & Geuens, 2009), as well as early adopters, hedonists and aesthetes (Hughes, 2005). Gay men and lesbians have been described as industry revivers, as they were the first to support the tourism and hospitality industry after the 9/11 events (Guaracino, 2007). On the other hand, Badgett (1997) and Carpenter (2004) have attempted to debunk the assumptions that gay men and women have more disposable income. Research shows that gay individuals often suffer from salary discrimination and therefore ‘using those [higher expenditure] numbers to describe all lesbian and gay people is misleading and, in many cases, deliberately deceptive’ (Badgett, 1997: 66). In recent years, an increasing number of married or cohabiting gay and lesbian couples are choosing to have children. An Australian Institute of Family Studies report stated that approximately 11% of gay men and 33% of lesbians in same-sex relationships in Australia have children (Dempsey, 2013).

The collective spending or purchasing power of the LGBTQI+ communities has been branded as the ‘pink dollar’, ‘pink pound’ or any other ‘pink currency’. In 2016, a study conducted by Roy Morgan (2016) found that 5.2% of Australian men and 3.1% of women agreed with the statement, ‘I consider myself homosexual’. While they comprise a relatively low proportion of the total population, gay men and lesbians tend to display distinct purchasing behaviours that reveal their value as a consumer group (Roy Morgan, 2016). The realisation that LGBTQI+ people might possess a distinct purchasing behaviour has resulted in a ‘pinkwashing’ phenomenon, whereby companies, destination management organisations and even politicians engage in a variety of marketing strategies to promote products, destinations or ideas by publicising gay-friendliness and inclusivity. As such, they are perceived as progressive, modern and tolerant. ‘Pinkwashing’ is problematic as it appropriates the LGBTQI+ movement to promote a corporate or political agenda; Dahl (2014) explains:

...