- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Shaping our cities, streets and public spaces, urban design informs the places we live. It is a complex multi-disciplinary process, requiring the input of a wide variety of stakeholders and design and construction professionals. Each urban project invariably throws up a new set of problems and strategic decisions for the design team. This guide distils the essential information required for the expert direction of the day-to-day work of urban design, from strategic design to masterplanning through to character assessment and collaboration. Compact and accessible with over 250 hand-drawn figures and plans, it's the perfect everyday companion for junior practitioners and experienced heads alike across the built environment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Essential Urban Design by Rob Cowan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

PLACE, PIONEERS AND PRACTITIONERS

INTRODUCTION

Urban design focuses on three questions: What do we know about this place? How can the place change? Who will benefit from that change? We think about those matters through appraisals, briefs, policies, guidance, strategies, masterplanning and development schemes. In each case the thinking, planning and designing processes involve a wide range of people. They include local authority planning officers, who prepare local planning policy and guidance, and assess the quality of planning applications; councillors, who provide political leadership and make planning decisions; applicants and their design teams, who prepare applications for planning permission; people in local communities and their representatives; and a wide range of other professionals (urban designers, architects, planners, landscape architects, surveyors, highway engineers and building conservationists among them) who are, in the widest sense of the term, urban designers. This book is for all of them.

When it was being written, the government in England was proposing a major reform of the planning system, hoping to achieve deregulation, on the one hand, and higher standards through design coding, on the other. It will be some years before we know how that turns out. Progress can be traced through the latest versions of the government’s Planning Policy Framework and the online Planning Practice Guidance. Here we focus on the essence of urban design. Chapter 1 (Place, Pioneers and Practitioners) tells the story of how the ideas behind urban design evolved. Chapter 2 (Eight Design Objectives and How to Achieve Them) shows how these ideas can be applied. Chapter 3 (Context, Character and Quality) explains how applying the ideas needs to be based on understanding the place, and how the end result can be judged. Chapter 4 (Politics, Collaboration and the Role of Local Authorities) looks at urban design in its political setting. Chapter 5 (Strategic Urban Design and Masterplanning) shows it working at the large scale.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

First, a definition. Urban design is the process of planning for land use and of devising the physical form of development in cities, towns and villages. You might ask: is that not equally a definition of planning? Yes, it is, if the planning process in question focuses on the physical form of development, rather than on the uses alone. But too often planning lacks that dimension, which is why urban design emerged as a distinct field of activity.

There are two things wrong with the term ‘urban design’. The first is the word ‘urban’. It tends to make people think of development in towns and cities, whereas urban design is concerned with settlements of all sizes, including villages and rural settings. The second thing wrong with the term urban design is the word ‘design’. It makes many people think of what architects and landscape architects do, rather than the much wider range of skills and activities involved in making places.

If urban design is such a problematic term, why use it? The first answer is that it has become established, at least in a professional context. The more familiar the term becomes, the less likely people are to agonise about the meaning of its two component words. It is true that the term might be misleading to people outside the professional world who are unfamiliar with it, but none of the alternatives are less confusing. Some alternatives have been tried. ‘Placemaking’, for example, has been fairly widely used as an alternative to urban design, but recently its association with controversial schemes to redevelop council housing estates has led to it acquiring negative connotations. The term urban design has never lost its innocence in that way, and it is a convenient term to use for a professional audience. There is no simple, abstract term that will convey to laypeople what this complex subject involves.

Urban designers analyse places, write policies and guidance, draw up masterplans and design codes, review the quality of building proposals, and design development schemes and spaces, among much else, working at every scale from a region to a single building. Urban design as we know it today has evolved through the efforts of people with a passion for finding practical means of understanding places, bringing about change, and ensuring that the right people benefit from that change. Through the stories of those pioneers we can trace the development of knowledge, techniques and movements that this book outlines.

PIONEERS OF URBAN DESIGN

If urban design is the answer, what is the question? Probably the question is ‘What makes a successful place?’

1.3: Sir Henry Wotton

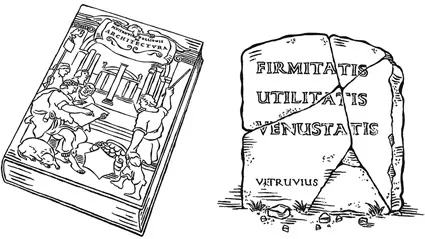

In the first century BC the Roman writer, architect and engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (commonly known as Vitruvius) defined the essentials of architecture in his treatise De architectura. There were three essentials, he wrote: ‘firmitatis, utilitatis, venustatis’ (Figures 1.1 and 1.2). People have been translating those terms ever since. Most famously, and much quoted, Sir Henry Wotton in 1624 translated them as (with archaic spellings) ‘commoditie, firmenes and delight’. Firmness and delight are easy enough to understand in relation to buildings, and ‘commoditie’ has been generally understood as meaning ‘usefulness’. Later, in the 1670s, Sir Christopher Wren defined the principles of architecture as ‘beauty, firmness and convenience’. In 2001 the Construction Industry Council used the three concepts as the basis for developing a set of performance indicators for buildings. Its equivalent terms, translated into contemporary industry jargon, were ‘functionality, build quality and impact’.

1.1: De architectura and the essentials of architecture

1.2: Vitruvius

1.4: Sir Christopher Wren

Many writers have used those three terms, in one way or another, to describe the essentials of urban design. What makes a successful place? It is fit for purpose, it is well built, and it delights the people who use it or see it. That is a good start. But we need a set of criteria that will help us to design successful places, and to explain to others what we want to achieve.

1.5: Augustus Pugin

A look back to the nineteenth century shows how the ideas behind urban design developed. Debate raged about both architectural style and the future development of towns and cities. In Contrasts, published in 1836, the architect and designer Augustus Pugin (1812–52) compared the meanness of the architecture of contemporary towns and cities to the glories of the medieval Gothic. He wrote in 1842 that reforming church architecture was an ambition ‘not inferior to the rescuing of the Holy Land from the Infidels’.1 His was a major influence on the widespread use of the Gothic. He famously collaborated with Charles Barry on the design of the Houses of Parliament, although he felt his (Pugin’s) Gothic detailing was merely cloaking what was essentially a classical building.

1.6: John Ruskin

The writer, social commentator, and critic of art and architecture John Ruskin (1819–1900) was, like Pugin, an influential advocate of Gothic architecture for important buildings, and a fierce opponent of industrial methods, not least in building. Ruskin’s writings inspired not only architects but also a generation of social reformers.

1.7: Octavia Hill

Octavia Hill (1838–1912) was a pioneer of many aspects of community development. She developed social housing (provided for social purposes, rather than for profit), housing management (meeting a landlord’s obligations) and social work (supporting people to improve their lives), and she campaigned for open space. She began by managing three houses that John Ruskin had bought to house unskilled labourers. Her example showed how such housing could be managed in the interests of the tenants, and how supporting the tenants’ lives, work and education could help to lift them out of poverty. Eventually she was managing thousands of houses. Her conviction that the urban poor needed places to sit in, to play in, to stroll in and to spend a day in led her to become one of the three founders of the National Trust, whose mission was to protect open spaces and endangered buildings of historic interest.

William Morris (1834–96), the writer, designer and campaigner for socialism, called for architecture based on handicrafts and people’s love for their work, and he advocated the creation of new small communities. He and Ruskin inspired the Arts and Crafts movement, which began in the UK as a reaction to the dehumanising effects of nineteenth-century industrialisation, and flourished between around 1875 and 1915.

1.8: William Morris

The Arts and Crafts movement was more an ethic than an aesthetic, at least initially. Its architectural leading lights were committed to reviving traditional building and craft skills, using local materials and seeking inspiration from the local vernacular. Later Arts and Crafts designers and architects saw it more as an aesthetic, while still advocating high standards of craftsmanship and inspiration from vernacular buildings. The influence of the movement on the urban landscape was immense in the first decade of the twentieth century. In the interwar years of the 1920s and 1930s speculative builders and local housing authorities took it up and made Arts and Crafts – with such features as hips and gables, half-timbering, roughcast walls, leaded ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Place, Pioneers and Practitioners

- 2: Eight Design Objectives and how to Achieve them

- 3: Context, Character and Quality

- 4: Politics, Collaboration and the Role of Local Authorities

- 5: Strategic Urban Design and Masterplanning

- Appendix: Checklist for Assessing Context and Character

- Notes

- Index

- Image Credits