![]()

1

Why Worker Health and Productivity Matter

Interest in workforce health has never been more intense. Before 2020 most developed economies were grappling with the challenges of ageing workforces, later retirement leading to longer working lives, widening health inequality and the growing prevalence of chronic ill-health in the working age population. Then Covid-19 arrived, catapulting working age health to the top of the public health, business and policy agendas simultaneously. The concepts of the healthy worker, health promoting workplace and safe return to work all took on a new importance. The human resources (HR) and occupational health (OH) professions were in the spotlight like never before, advising CEOs and boards about safe working, the health of frontline workers or the well-being of the new army of homeworkers who found themselves in remote teams.

Perhaps no group has come under more scrutiny than line managers, whose capacity to manage the rapid pivoting of working arrangements while exercising stewardship over the human resources under their care was tested daily. For them, the responsibility for ensuring that workforce well-being and productivity were being protected and optimised was intense. Most rose brilliantly to the challenge, but others were cruelly exposed as being out of their depth. We also found out that worker health has much less to do with having access to fruit and Pilates lessons than we ever imagined. Perhaps more than anything the pandemic has forced employers to think deeply about the ways that investing in workforce health can enhance agility, resilience, resourcefulness and productivity both during the pandemic and beyond.

It is the ‘sweet spot’ at which worker well-being and productivity meet which is the focus of this book. In particular, in an economic environment in which productivity is acknowledged as a policy priority but which is only rarely measured reliably in most organisations, we try to make the concept of productivity more accessible and grounded for those practitioners who are searching for ways of harnessing the business benefits of a healthy workforce.

We start in Chapter 2 with an overview of the evidence about the relationship between health and work and productivity. We deliberately go beyond traditional measures of ‘productivity’ – sickness absence, accidents and presenteeism – to take into account some of the more macroeconomic, labour market and task performance definitions of productivity at work. It is in this chapter that we also lay the foundations for a central theme of the book – that workforce health is an asset and that terms such as ‘burden’ and ‘risk’, while important, can overplay the negative connotations associated with ill-health at work.

In Chapter 3 we focus on the lessons that have been learned so far from the pandemic and the ways that organisations, healthcare professionals and policymakers have responded. We look in detail at the challenges of working from home and its impact on physical and psychological well-being, sleep, fatigue, job satisfaction and work–life balance. We also look at emergent research on ‘moral injury’, burnout and ‘long Covid’.

In Chapter 4 we look specifically at the role of line managers. We look at the characteristics of line managers who manage the well-being of their employees professionally and with empathy, authenticity and compassion. We ask whether line managers bear too much of the burden of managing all aspects of employee health and well-being. We also consider what can be done to enhance their capability and enable them to be the most important custodians of the link between health and productivity.

The role of healthcare professionals in improving workforce health is the focus of Chapter 5. For many years general practitioners in primary care have been in the front line of sickness certification and have reluctantly played a role in advising employees and their employers about the conditions in which return to work may be made possible. However, this has always been a contested role and we look at ways of overcoming this barrier. We scrutinise the ways other healthcare professionals in occupational medicine, secondary care and vocational rehabilitation also play a part in helping work to become a clinical outcome of care.

In Chapter 6 we take a look at the evidence for a range of workplace health interventions. For many practitioners there is real confusion about which measures have the strongest evidence base. Many are bewildered by the array of claims made for different interventions and want to know, as they have limited resources, where to invest their time and money to maximise a return on their investment. This chapter provides a contemporary overview of the latest research evidence and attempts to help confused employers to differentiate between practices which have high ‘face validity’ and those with a proven track record of success.

In Chapter 7 we ask a fundamental question about the ways we could ensure that workforce health could be seen as an asset rather than as a liability. Perhaps too frequently, ill-health in the working age population is regarded as a burden or a drain on productivity, and a risk to be mitigated. This chapter looks at the arguments for thinking about workforce health as an appreciating asset. We look at the role which might be played by the investment community in demanding that more businesses provide transparent reporting about the health of their workforces and the steps they are taking to improve well-being and productivity among their employees. At a more ‘micro’ level we also examine aspects of employee personality such as conscientiousness and assess the extent to which organisations who are able to draw upon these psychological assets may have the double benefit of both enhanced health and improved performance that work.

Finally, in Chapter 8 we look at five areas which we believe will be among the main drivers of workforce health in the future. Here the role of managers and leaders and OH professionals are put under the microscope, and we explore how they can play a more prominent and self-confident role. We argue that more investment in risk assessment and prevention at work could prevent downstream costs and complex cases. The post-pandemic world of workplace health is also a focus in this chapter, as we identify some of the positive lessons of Covid-19 which could permanently improve the heath of workers into the future. We also pose a final challenge to employers about the ways they can harness worker health to drive forward improvements in business performance and productivity.

Labour productivity after the 2008 financial crisis remained sluggish in most economies because too many policymakers and businesses became tangled in a debate about the impact of investment in skills and technology. As we emerge from a global pandemic – and another global recession – this book seeks to make a powerful case for investment in a hitherto underestimated ‘factor of production’, worker health and well-being. While for those of us who have been advocates of promoting well-being at work this is not an especially new idea. However, we are convinced that, for the uninitiated, it is an idea whose time has come.

![]()

2

How Health Affects Productivity

2.1 The Context – Health as a ‘Factor of Production’

The oft-quoted axiom that healthy workers are productive workers has become very familiar over the last decade or so. It is hard to disagree that helping employees to stay healthy will also help them to remain in employment, to attend work regularly and to perform well in their jobs. Indeed, even at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution the British Social Reformer, John Ruskin, wrote in 1851:

…in order that people be happy in their job, these three things are needed: they must be fit for it, they must not do too much of it and they must have a sense of success in it.

Additionally, who among a range of stakeholders such as governments, businesses, healthcare professionals and employees do not stand to gain either directly or indirectly from the gains in productivity which flow from a fitter and high-functioning workforce? Yet productivity is, itself, a multi-faceted and complex phenomenon and one which has only recently been scrutinised with rigour in the context of workforce health. Historically, its use has been mainly confined to the fields of economics and business as it is mostly thought of as a measure of the output of goods and services – from an economy, an industrial sector or a firm – which then become available for some form of financial exchange.

However, as the discipline of economics has developed, different aspects of productivity have been the subject of both theoretical and practical focus. For example, ‘labour productivity’ is more specifically about the amount of work (outputs) produced by an employee for each hour they work (inputs). The concept of the ‘production function’, where the combined effects of capital (e.g. equipment, machinery or information technology) and labour (e.g. the skills and efforts of employees) can be observed, quantified, modelled and forecast, has provided labour economists with ways of exploring why productivity varies over time and between nations, regions, sectors or firms. More complex still, the idea of ‘total factor productivity’ looks at ways of attaching an economic value to some of the intangible assets which a business or an economy might be able to bring to bear to productive capacity through the application of R&D, know-how, the power of ‘branding’ and so on. It might be argued that workforce health might represent such an intangible asset if a standardised way of quantifying it could be agreed upon. More on this later.

For the purposes of this chapter, we will not dwell so much on competing economic theories of productivity, but focus more on the various ways that ‘workforce health’ may be linked to the ‘enhancement of productive capacity’. Even here, issues of definition, measurement, costs and benefits are not always straightforward, but we hope to set out a simplified way of thinking about the terrain, and to identify the most effective ways which both theory and practice show us that we can optimise the health of the workforce for both economic and social benefit.

In this chapter we will look at the different ways that health can affect labour productivity. From the outset, it is important to recognise that the health–productivity dynamic manifests itself in different ways depending on the context within which it is being measured. For example:

- Somebody of working age who has decided to work part-time, has left work permanently or who has died as a result of ill-health is, de facto, reducing their productive contribution to the economy and to the labour market.

- An employee who has frequent absences from work, or who cannot fulfil all of the responsibilities of their job as a result of ill-health, or comes to work regularly but whose physical or cognitive function is impaired is also reducing their productive capacity, especially to the organisation which employs them.

- A colleague who is returning to work on a phased or graduated basis after a lengthy period of sick leave as a result of an injury or illness requiring medical treatment and rehabilitation is likely to be less productive during their return to work than before they went sick. Nonetheless, even a phased return to work is better for both them and their employer than an even more lengthy absence.

The practical benefits of being clear about the ways that workforce health and productivity are connected is that we can begin to identify both the steps which can be taken to prevent and minimise health-related productivity loss and maximise the likely economic, business and societal benefits of doing so (Public Health England, 2015). Let's begin by looking at some of the most helpful ways of categorising the health and productivity link.

2.2 Three Ways of Thinking about Health and Productivity

When we think about the relationship between worker health and productivity, there is perhaps an inevitable focus on those factors which inhibit both productive inputs and outputs – that is to say, the hours or efforts which workers can devote to work and the quantity, quality and value of what they produce. However, it is also important to pay attention to those factors which facilitate productivity. Some of these will relate directly to the prevention, mitigation or improvement of productivity inhibitors (e.g. improving sleep quality which then leads to improved energy and vitality at work or reduced absence or accidents) or the enhancement of facilitators to improve inputs or outputs (e.g. early intervention to support job retention and return to work). Others may be ‘system-level’ factors which can unlock the way these elements work either singly or together (e.g. approaches to sickness certification in Primary Care, health technology appraisal, welfare system rules, access to healthcare or siloed budgets). So, improving productive capacity is not always just about ‘fixing’ the factors which inhibit productivity – it can be about both improving the facilitating factors and making the system-level factors more benign (many of these are more likely to be under the control of policymakers than employers).

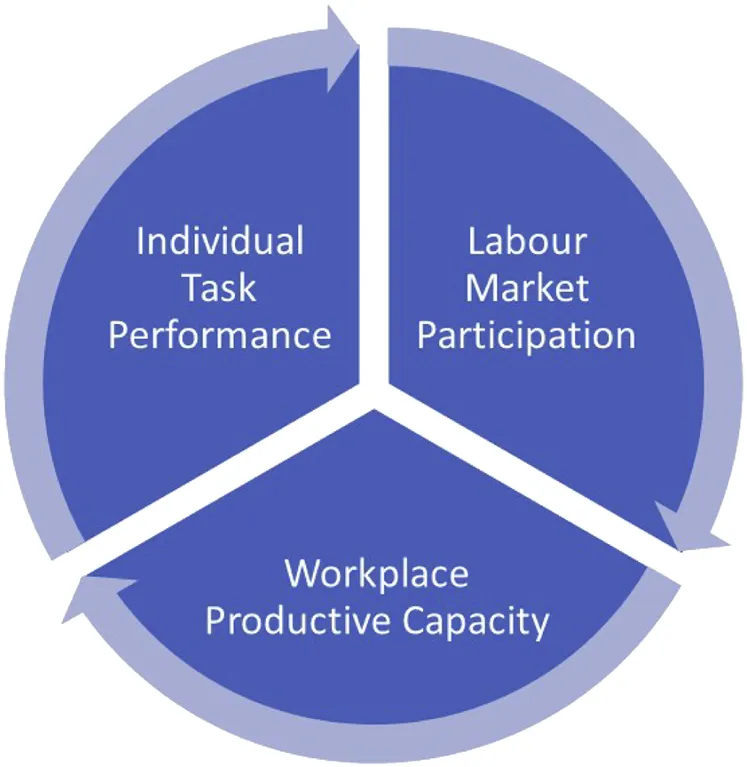

To help us navigate this terrain, it is worth setting out and exploring the three dominant ways which researchers, clinicians and economists typically conceptualise the relationship between health and work. These are set out in Fig. 2.1.

Source: Author's original work.

Fig. 2.1. Three Dimensions of the Health and Productivity Relationship.

Looking at these dimensions in more detail, they have the following characteristics and components:

- The Labour Market Participation Definition: here the focus is level of labour market participation in the wider workforce which is linked to having a health condition (or multiple conditions). This can include mortality, high levels of underemployment or reduced hours working, differential employment rates for people with chronic ill-health or disabilities, premature withdrawal from work, early retirement on the grounds of ill-health. These factors tend to represent constraints on the INPUT side of the productivity equation and can be affected by demographic trends (e.g. ageing) by epidemiological trends (more chronicity, growth in ...