- 317 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

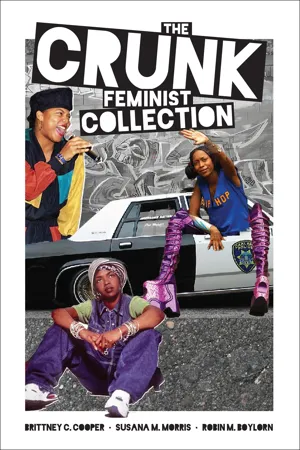

The Crunk Feminist Collection

About this book

Essays on hip-hop feminism featuring relevant, real conversations about how race and gender politics intersect with pop culture and current events.

For the Crunk Feminist Collective, their academic day jobs were lacking in conversations they actually wanted. To address this void, they started a blog that turned into a widespread movement. The Collective's writings foster dialogue about activist methods, intersectionality, and sisterhood. And the writers' personal identities—as black women; as sisters, daughters, and lovers; and as television watchers, sports fans, and music lovers—are never far from the discussion at hand.

These essays explore "Sex and Power in the Black Church," discuss how "Clair Huxtable is Dead," list "Five Ways Talib Kweli Can Become a Better Ally to Women in Hip Hop," and dwell on "Dating with a Doctorate (She Got a Big Ego?)." Self-described as "critical homegirls," the authors tackle life stuck between loving hip hop and ratchet culture while hating patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism.

"Refreshing and timely." —Bitch Magazine

"Our favorite sister bloggers." —Elle

"By centering a Black Feminist lens, The Collection provides readers with a more nuanced perspective on everything from gender to race to sexuality to class to movement-building, packaged neatly in easy-to-read pieces that take on weighty and thorny ideas willingly and enthusiastically in pursuit of a more just world." —Autostraddle

"Much like a good mix-tape, the book has an intro, outro, and different layers of based sound in the activist, scholar, feminist, women of color, media representation, sisterhood, trans, queer and questioning landscape." —Lambda Literary Review

For the Crunk Feminist Collective, their academic day jobs were lacking in conversations they actually wanted. To address this void, they started a blog that turned into a widespread movement. The Collective's writings foster dialogue about activist methods, intersectionality, and sisterhood. And the writers' personal identities—as black women; as sisters, daughters, and lovers; and as television watchers, sports fans, and music lovers—are never far from the discussion at hand.

These essays explore "Sex and Power in the Black Church," discuss how "Clair Huxtable is Dead," list "Five Ways Talib Kweli Can Become a Better Ally to Women in Hip Hop," and dwell on "Dating with a Doctorate (She Got a Big Ego?)." Self-described as "critical homegirls," the authors tackle life stuck between loving hip hop and ratchet culture while hating patriarchy, misogyny, and sexism.

"Refreshing and timely." —Bitch Magazine

"Our favorite sister bloggers." —Elle

"By centering a Black Feminist lens, The Collection provides readers with a more nuanced perspective on everything from gender to race to sexuality to class to movement-building, packaged neatly in easy-to-read pieces that take on weighty and thorny ideas willingly and enthusiastically in pursuit of a more just world." —Autostraddle

"Much like a good mix-tape, the book has an intro, outro, and different layers of based sound in the activist, scholar, feminist, women of color, media representation, sisterhood, trans, queer and questioning landscape." —Lambda Literary Review

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Crunk Feminist Collection by Brittney C. Cooper,Susana M. Morris,Robin M. Boylorn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Essays. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

GENDER: @#$% THE PATRIARCHY

Introduction

The essays in this section confront the numerous and varied ways patriarchy and gender norms marginalize women, girls, trans folk, and all things feminine. While patriarchy ultimately harms everyone, cisgender men and boys are rarely forced to reckon with the ways their lives, experiences, and concerns are valued at the expense of others. Our formal education does not teach us what is at stake for folk who are gender fluid, gender nonconforming, gender neutral, or same-gender loving. As crunk feminist Eesha Pandit has noted, “Sex and gender are different and there are more genders than two,” but in a patriarchal culture that privileges masculinity and maleness, binary categorization reinforces the hegemonic harms linked to the social construction of gender and the hegemonic harassment that insists masculinity be given social capital.

Just as gender is not synonymous with sex, it is not preoccupied with femininity. We approach gender as a contrived system designed to dictate how women and men (including trans and intersex folk) negotiate their roles and performances, in public and private. Many of us found feminism after recognizing and/or resisting the blatantly sexist and misogynist cultural expectations of how we were supposed to think, act, dress, and behave. The strict confines of gender scripts failed to represent the hybrid, fluid, androgynous spectrum of gender expression we experienced and witnessed in our lives. Gender was invented to restrict the performance of women and men to conservative and traditional behaviors, punishing nuances such as female masculinity or androgynous femme.

These limitations of gender are particularly problematic in Black communities because of the residue of Moynihan’s matriarchy thesis,1 the nuanced negotiation of gender in Black households, and the vulnerability of Black masculinity due to limited resources and opportunities linked to racism. Even though our social circumstances, allegiances to Black men, and devotion to Black churches have often complicated our relationship to raced gender performance, Black women can rarely afford to hold conservative or traditional attitudes about gender, which were designed with White women in mind. Because Black women are framed by images of independence, strength, and resilience, their gender performance, unlike White women’s, has often been read as an assault on Black manhood and evidence that Black women are inherently more masculine and, therefore, don’t deserve or require the same protection and provision as White women. Thus, Black feminism recognizes and calls out the racist agenda of gender categorization, particularly the ways it polices the bodies and actions of Black women.

Our work seeks to further complicate the already problematic relationship Black women have to the patriarchy, a relationship that is both abusive and one-sided. While we understand the myriad ways Black men are targeted for their own negotiation of gender, we refuse to prioritize the needs of men over women or to overlook the investments all men have in patriarchy because of their inherent privileges. We understand gender to be a social construction created to limit our options and access.

As crunk feminists we embrace the possibilities of gender performance, insisting that Black women and women of color be given the room and agency to make sense of who we are, outside of stereotypes. As women of color, we are intimately aware of the politics of identity, the role of racism in the ways our gender is read and understood, and the interconnection of our race, gender, sex, ability, sexuality, and class. Our allegiance to Black men—we are allied—is not an investment in patriarchy, because our feminism pushes us to challenge the status quo and demand equal standards.

We envision an understanding of gender that is inclusive and nonhierarchal; we imagine relationships that are reciprocal and not violent. We are also invested in the lives and experiences of our community and siblings, including all sexes and genders, and we are deeply invested in and committed to shifting our language practices and social justice commitments to be more gender inclusive.

Black women and girls are not generally offered the luxury of femininity. Women of color are faced with more than sexism in our homes, jobs, and communities. We face criticism when we express our independence from and solidarity with men, and receive backlash when we express our disappointment and frustration with their flagrant disregard for our lives and well-being. Many of us grew up witnessing our foremothers and other women in our lives demonstrate strength and independence out of necessity, never given the luxury or opportunity to be “kept women.” Places we were told to revere like churches and schools, as well as intimate spaces like our homes and bedrooms, were privately, if not publicly, sexist. We were encouraged (by women and men alike) to accept these unfair and unjust practices as normal.

The absence of men was never an absence of possibility. We were raised to be feminists (what our mamas called “having our own,” outside of a man), to get educated, to be capable of achieving our goals, to understand the function and functionality of female friendships, especially in households that were largely matriarchal. Still, the absence of men was never an absence of male reverence. Patriarchal influences permeated our lives and we, like Black feminists before us, had to learn and understand that our allegiance is to ourselves and that we cannot afford to be invested in patriarchal norms.

Feminism, which ultimately seeks equal rights and recognition for women and girls, and crunk feminism, which unapologetically and actively resists patriarchy by practicing, being, and performing “crunkness,” inform the impetus of this section. As crunk feminists, we are not invested in being polite, respectable, or politically digestible—because our very lives are on the line.

Women and girls are perpetually reminded that their lives are not valued, that their testimonies (against men) will not be believed, and that their well-being is unimportant when masculinity (including ego) and patriarchy are at stake. This was reinforced, for example, when the Black women assaulted by former police officer Daniel Holtzclaw said they felt that reporting him would be futile, and when the more than fifty women who have come forward as rape victims of Bill Cosby are framed as “accusers,” not victims. It is also reiterated through the documented double standard of the wage gap and the fact that Black women and trans women of color are disproportionately affected by violence that ends in death.

Patriarchy is invested in the normalization of masculinity in all of its manifestations (including rape culture and violence) and the silence and invisibility of women, especially women of color. The patriarchy tells us that women should stay in their place and not challenge authority. The patriarchy wants us to be misguided and misinformed. The patriarchy wants us to be defeated and disenchanted. Our essays on gender demonstrate resistance and refusal to comply with traditional, irrational, and patriarchal bullshit. Fuck the patriarchy!

1. The controversial Moynihan Report, written in 1965, concluded that the high rate of Black families headed by single mothers would greatly hinder the progress of Black communities toward economic and political equality.

Dear Patriarchy

Crunkista

Dear Patriarchy,

This isn’t working. We both know that it hasn’t been working for a very long time.

It’s not you . . . No, actually, it is you. This is an unhealthy, dysfunctional, abusive relationship—because of you. You are stifling, controlling, oppressive, and you have never had my best interests at heart. You have tricked me into believing that things are the way they are because they have to be, that they have always been that way, that there are no alternatives, and that they will never change.

Anytime I question you or your ways, you find another way to silence me and coerce me back into submission. I can’t do this anymore. I’ve changed and in spite of your shackles, I’ve grown. I have realized that this whole restrictive system is your own fabrication and that the only one gaining anything from it is you. You selfish dick.

I will not continue to live like this. I will not continue to settle. I know now that there is a better way.

Before you hear about it from one of your boys, you should know that I have met someone. Her name is Feminism. She is the best thing that has ever happened to me. She validates and respects my opinions. She always has my best interests at heart. She thinks I am beautiful and loves me just the way I am. She has helped me find my voice and makes me happier than I have ever been. We have made each other stronger. Best of all, we encourage and challenge each other to grow. And the sex . . . Well, the sex is so much hotter.

I’m leaving you. You’re an asshole. We can never be friends. Don’t call me. Ever.

Never again,

Crunkista

On Black Men Showing Up for Black Women at the Scene of the Crime

Brittney C. Cooper

In 2013 I showed up to the Brecht Forum in Brooklyn ready to have a conversation about what we mean when we say “ally,” “privilege,” and “comrade.”

I showed up to have that discussion after months of battle testing around those issues in my own crew. Over the years, I’ve learned that it is far easier to be just to the people we don’t know than the people we do know.

So there I sat on a panel with a White woman and a Black man. As a Black feminist, I never quite know how political discussions will go down with either of these groups. Still, I’m a fierce lover of Black people and a fierce defender of women.

The brother shared his thoughts about the need to “liberate all Black people.” It sounded good. But since we were there to talk about allyship, I needed to know more about his gender analysis, even as I kept it real about how I’ve been feeling lately about how much brothers don’t show up for Black women, without us asking, and prodding, and vigilantly managing the entire process.

In a word, I was tired.

I shared that. Because surely a conversation about how to be better allies to each other is a safe space.

This brother was not having it. He did not want to be challenged, did not plan to have to go deep, to interrogate his own shit. Freedom talk should’ve been enough for me.

But I’m grown. And I know better. So I asked for more.

I got cut off, yelled at, screamed on. The moderator tried gently to intervene, to ask the brother to let me speak, to wait his turn. To model allyship. To listen. But to no avail. The brother kept on screaming about his commitment to women, about all he had “done for us,” about how I wasn’t going to erase his contributions.

Then he raised his over-six-foot-tall, large, Brown body out of the chair and deliberately slung a cup of water across my lap, leaving it to splash in my face, on the table, on my clothes, and on the gadgets I brought with me.

Damn. You knocked the hell out of that cup of water. Did you wish it were me? Or were you merely trying to let me know what you were capable of doing to a sister who didn’t shut her mouth and listen?

Left to sit there, splashes of water, mingling with the tears that I was too embarrassed to let run, because you know sisters don’t cry in public, imploring him to “back up,” to “stop yelling,” to stop using his body to intimidate me, while he continued to approach my chair menacingly, wondering what he was going to do next, anticipating my next move, anticipating his, being transported back to past sites of my own trauma . . .

I waited for anyone to stand up, to sense that I felt afraid, to stop him, to let him know his actions were unacceptable. Our copanelist moved her chair closer to me. It was oddly comforting.

I learned a lesson: everybody wants to have an ally, but no one wants to stand up for anybody.

Eventually three men held him back, restrained him, but not with ease. He left. I breathed. I let those tears that had been threatening fall.

Then an older Black gentleman did stand up. “I will not stand for this maligning of the Black man . . . ,” his rant began. While waiting for him to finish, I zoned out and wondered what had happened here.

Did this really happen here? In movement space?

Tiredness descended. And humiliation. And loneliness. And weariness. And anger at being disrespected. And embarrassment for you. And concern for you and what you must be going through—to show your ass like that. And questioning myself about what I did to cause your outburst. And checking myself for victim blaming myself. And anger at myself for caring about you and what you must be going through. Especially since you couldn’t find space to care about me and what I must be going through.

Later, with my permission, you came in and apologized. Asked us to make future space for forgiveness. I didn’t feel forgiving that day. I don’t feel forgiving today. I know I will forgive you though. It’s necessary.

After being approached at the end by a Gary Dourdan–looking macktivist, who couldn’t be bothered to stand up to the brother screaming on me, but who was ready to “help” me “heal the traumas through my body”—as he put it (yes, you can laugh)—I grabbed my coat and schlepped back to Jersey.

On the long train ride home, and in the days since, I was reminded that that was not the first time I had been subject to a man in a movement space using his size and masculinity as a threat, as a way to silence my dissent. I remembered that then as now, the brothers in the room let it happen without a word on my behalf.

Why?

Is it so incredibly difficult to show up for me—for us—when we need you? Is it so hard to believe that we need you? Is solidarity only for Black men? As for the silence of the sisters in the room, I still don’t know what to make of that. Maybe they were waiting on the brothers, just like me.

I do know I am tired. And sad. And not sure how much more I want to struggle with Black men for something so basic as counting on you to show up.

The Evolution of a Down-Ass Chick

Robin M. Boylorn

Down-Ass Chick: a woman who is a lady but can hang with thugs. She will lie for you but still love you. She will die for you but cry for you. Most impo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- The Crunk Feminist Collective Mission Statement

- Hip Hop Generation Feminism: A Manifesto

- Intro: Get Crunk!

- PART I: GENDER: @#$% THE PATRIARCHY

- PART II: RACE AND RACISM: ALL BLACK LIVES MATTER

- PART III: FAMILY AND COMMUNITY: CHOOSING FAMILY

- PART IV: GIRLS STUDIES: BLACK GIRLS ARE MAGIC

- PART V: POLITICS AND POLICY: THE PERSONAL IS POLITICAL

- PART VI: HIP HOP GENERATION FEMINISM: FEMINISM ALL THE WAY TURNED UP

- PART VII: LOVE, SEX, AND RELATIONSHIPS: BLACK FEMINIST SEX IS . . . THE BEST SEX EVER

- PART VIII: POP CULTURE: THE RISE OF THE RATCHET

- PART IX: IDENTITY: INTERSECTIONALITY FOR A NEW GENERATION

- PART X: SISTERHOOD: SHE’S NOT HEAVY, SHE’S MY SISTER

- PART XI: SELF-CARE: THUS SAITH THE LORDE

- Outro

- Crunk Glossary

- Contributor Bios

- Acknowledgments

- Also by the Feminist Press

- About the Feminist Press