- 388 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"[Allred] interrogates Beyoncé's music and videos to explore the complicated spaces where racism, sexism, and capitalism collide." —

Kirkus Reviews

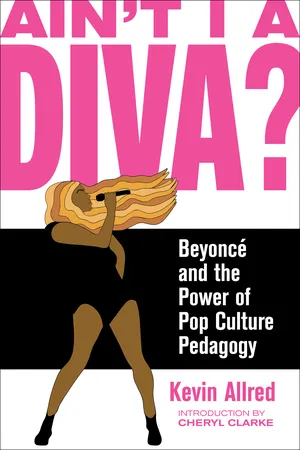

In 2010, Professor Kevin Allred created the university course "Politicizing Beyoncé" to both wide acclaim and controversy. He outlines his pedagogical philosophy in Ain't I a Diva?, exploring what it means to build a syllabus around a celebrity. Topics range from a capitalist critique of "Run the World (Girls)" to the politics of self-care found in "Flawless"; Beyoncé's art is read alongside black feminist thinkers including Kimberlé Crenshaw, Octavia Butler, and Sojourner Truth. Combining analysis with classroom anecdotes, Allred attests that pop culture is so much more than a guilty pleasure, it's an access point—for education, entertainment, critical inquiry, and politics.

"Proving himself a worthy member of the BeyHive, Kevin Allred takes us on a journey through Beyoncé's greatest hits and expansive career—peeling back their multiple layers to explore gender, race, sexuality, and power in today's modern world. A fun, engaging, and important read for long-time Beyoncé fans and newcomers alike." —Franchesca Ramsey, author of Well, That Escalated Quickly

"Ain't I a Diva? explores the phenomenon of Beyoncé while explicitly championing not only her immense talent and grace but what we can learn from it. In this celebration of Beyoncé, and through her, other Black women, Allred is giving us room to be exactly who we are so that maybe we, too, can stop the world then carry on!" —Keah Brown, author of The Pretty One

"A must-read for any fan of Beyoncé and of fascinating feminist discourse." —Zeba Blay, senior culture writer, HuffPost

In 2010, Professor Kevin Allred created the university course "Politicizing Beyoncé" to both wide acclaim and controversy. He outlines his pedagogical philosophy in Ain't I a Diva?, exploring what it means to build a syllabus around a celebrity. Topics range from a capitalist critique of "Run the World (Girls)" to the politics of self-care found in "Flawless"; Beyoncé's art is read alongside black feminist thinkers including Kimberlé Crenshaw, Octavia Butler, and Sojourner Truth. Combining analysis with classroom anecdotes, Allred attests that pop culture is so much more than a guilty pleasure, it's an access point—for education, entertainment, critical inquiry, and politics.

"Proving himself a worthy member of the BeyHive, Kevin Allred takes us on a journey through Beyoncé's greatest hits and expansive career—peeling back their multiple layers to explore gender, race, sexuality, and power in today's modern world. A fun, engaging, and important read for long-time Beyoncé fans and newcomers alike." —Franchesca Ramsey, author of Well, That Escalated Quickly

"Ain't I a Diva? explores the phenomenon of Beyoncé while explicitly championing not only her immense talent and grace but what we can learn from it. In this celebration of Beyoncé, and through her, other Black women, Allred is giving us room to be exactly who we are so that maybe we, too, can stop the world then carry on!" —Keah Brown, author of The Pretty One

"A must-read for any fan of Beyoncé and of fascinating feminist discourse." —Zeba Blay, senior culture writer, HuffPost

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ain't I a Diva? by Kevin Allred in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sciences sociales & Théorie et appréciation de la musique. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AIN’T I A DIVA?

“WHO IS BEYONCÉ?”

It’s the first question I ask students to ponder on the first day of class. A question meant to be deceptively complex. A question used to tease out the level of familiarity with Beyoncé students bring to the classroom, any assumptions about her career they might hold, and any various attachments they have to her music. Of course, no prior knowledge or familiarity is necessary—her songs and videos become texts, just like any other readings in any other traditional course. I have, on occasion, had a few students who knew nothing about Beyoncé sign up; they just wanted a break from the monotony of their regular studies. I’ve even had a Beyoncé antagonist or two enroll to play devil’s advocate, but they still have to ground their criticism in textual analysis. All opinions are welcome. It’s much more common, however, that students sign up because they’re already avid fans—whether or not they claim full-fledged BeyHive membership—or at least casual listeners of pieces or all of Beyoncé’s catalog. Some students are new fans; some have been listening for as long as they can remember. As years go by, students even become less likely to know a life before Beyoncé—an eighteen-year-old today was born in 2001 and Destiny’s Child’s self-titled debut album was released in 1998. Regardless, some students and fans have identity-based attachments; some love the themes and content, even though they don’t reflect their own experiences. Most everyone shares a love of the music, though, across backgrounds and identities. In this introductory conversation, I ask students to share it all: what they personally love about Beyoncé, or even (gasp!) things that they aren’t as fond of, to draw out some of the above connections. It’s a nice way to form camaraderie on the first day, and beats the typical trite icebreaker.

The question also serves as a way to set up one of the foundational aspects of the course that can never be overstated: analysis of Beyoncé will focus on Beyoncé as a performer and artist, not Beyoncé as a private person. So as everyone shares their personal associations and reactions, and even a little gossip, I try to point out the differences between analyzing Beyoncé’s performances critically and gossiping or making assumptions about her personal life based on her music—which isn’t to say her personal life isn’t part of her music, but so much of what the public thinks they know about Beyoncé’s personal life is conjecture. Those watching may suspect certain things, and lyrics and visuals may allude to some interpersonal drama, but they’re rarely addressed formally by Beyoncé herself outside of her art. In today’s social media culture, fans have near-constant access to their favorite celebrities, but Beyoncé has emphatically drawn a line between her public persona and private life, especially since 2013. She is one of few celebrities, if not the only one of her caliber, with such strictly defined boundaries. That delineation is something that gets highlighted again and again over the course, especially when conversations and analysis veer too close to personal assumptions.

Viewing Life Is But a Dream, Beyoncé’s 2013 documentary, as a form of visual autobiography together at the beginning of the semester helps drive this point home. The film is a master class in sleight of hand—Beyoncé gives the audience an intimate look at her life and work while still offering few specific facts about her private existence. She literally brings viewers up to the front door of her childhood home in the opening shots, but leaves that door closed, even as she offers vulnerable and intimate behind-the-scenes snippets. All the while, the door serves as a symbolic boundary; it never opens. Those private moments are carefully curated and the audience returns to and moves back from that still-closed door at the end of the film, reminding everyone to respect the barrier between Beyoncé’s private and public selves. To give her space to be an artist and create—the same space and consideration regularly afforded white male artists.

Another introductory exercise I use to highlight Beyoncé as a public artist is to contextualize her place in the longer history of Black women in music. Students are asked collectively to create a timeline of artists who they think map out a trajectory of inspiration, without whom the rise of Beyoncé would have never been possible. To mark the connections between Black women’s musical contributions back through time. Many of the artists named during this initial exercise reappear at other moments during the semester too, either named by Beyoncé as specific influences or referenced more generally and artistically through her work or other sources. Bessie Smith, Josephine Baker, Billie Holiday, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, Dinah Washington, Etta James, Nina Simone, Aretha Franklin, Mahalia Jackson, The Supremes, Diana Ross, Tina Turner, Grace Jones, Donna Summer, Natalie Cole, Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston, Ms. Lauryn Hill—just to name a few. Of course, many other artists of other backgrounds and identities play pivotal roles in Beyoncé’s development, but the timeline remains focused on Black women in music exclusively.

So, again, who is Beyoncé? It’s not a question that’s meant to be answered, really. It’s a question to mull over for the entire course and untold time to come. Yes, she’s a performer, singer, songwriter, actress, visual artist, musical genius, Black woman in the US, business mogul, mother, wife, daughter, sister, icon. She’s all those things and countless more. She’s also, to quote Jamaican performance poet Staceyann Chin, “Never one thing or the other.” Beyoncé is complicated and inhabits multiple identities and positions. I might even add feminist and queer theorist to the list based on analyses of her work. She’s all of the above and more; at other times, she’s none of those things, and possibly something else entirely. Never one thing or the other. Beyoncé is a piece of history and history in the making. And during a memorable 2008 song, Beyoncé importantly self-identifies as a diva. What is a diva? A diva is also never one thing or another, and a diva is intersectional too. To understand how the idea of the diva functions in Beyoncé’s catalog, students must travel back to one of the earliest points in history on the syllabus—not just back through Black women’s musical contributions but Black women’s activism as well—to Sojourner Truth and her work publicly interrogating race and gender, alongside other systems. All of which get further developed later, but this initial interrogation jump-starts thinking. Obviously, Beyoncé and Sojourner Truth share more differences than commonalities, but it’s still useful to name the ways in which Beyoncé might be carrying Truth’s truth forward.

Ain’t I a Woman?

Sojourner Truth has long been heralded as a Black feminist icon and symbol, representing critique of the often-single-issue focus of both the abolitionist and women’s rights movements in the mid- to late 1800s. As Angela Davis states in Women, Race & Class, “If most abolitionists viewed slavery as a nasty blemish which needed to be eliminated, most women’s righters viewed male supremacy in a similar manner—as an immoral flaw in their otherwise acceptable society.” Truth knew society was much more deeply flawed and refused to be silent. Her “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, given at the 1851 Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, has become a staple in both women’s and gender studies and African American studies classrooms. It powerfully critiques a divide that continues to this day in feminist movements. You can find YouTube video performances of the speech by actresses Kerry Washington and Alfre Woodard; it’s been memorialized as the title of bell hooks’s first book, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, and even used by actress and activist Laverne Cox in her university speaking engagements, inflecting the phrase with additional important political commentary on gender.

Trouble is, the version of Truth’s speech celebrated today likely never happened. Truth left no first-person writing or records of the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech, as she never learned to read or write, and it was reportedly delivered extemporaneously. She did publish the Narrative of Sojourner Truth, as transcribed by a friend, but her speeches don’t appear, only her life story. Nell Irvin Painter traces the history of Sojourner Truth in the definitive account of her life, Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. She notes that the version of the speech anthologized today was recorded by Frances Dana Gage in 1863, allegedly from her own twelve-year-old memories of the convention, and is, according to Painter’s meticulous research, “by no means the real Sojourner Truth.” Despite the inaccuracies and sometimes direct contradictions to the only other record of the speech—by Marius Robinson in 1851, with none of the dramatic flourish of Gage’s account, and none of the dialect which might be considered racist when recorded by Gage, especially because Truth was brought up speaking Dutch and likely had none of the speech patterns memorialized—Painter says Gage’s account persists because of its power as performance.

Though the dramatic phrasing and gestures associated with the speech everyone reads, quotes, and performs today are likely incorrect, the sentiment and content do fall in line with Sojourner Truth’s overarching work to dismantle racism and sexism at their intersections. In fact, Truth was often even more radical than she is usually given credit for, fiercely attacking capitalism as the very system from which racial and gender difference are created. Truth was born into slavery around 1797 as Isabella Baumfree (she later adopted the surname Van Wagenen) but escaped with one of her daughters in 1826. She later sued white owners in that same year to have her son returned to her and won, becoming the first Black woman to ever win a lawsuit against a white man, a major feat in and of itself. She eventually took on the name Sojourner Truth, meaning walking truth teller, in 1843 after feeling called by God to spread her message. She toured not unlike a contemporary performer, captivating audiences with both oration and song, preaching religion but also demanding freedom for Black women as an abolitionist and women’s rights advocate simultaneously.

Beyoncé and Sojourner Truth are connected through performance and their affective pull on audiences. Truth’s commanding presence and charisma were regularly referenced by those who witnessed her speeches. The same are often ascribed to Beyoncé. But the two also connect through content. Truth’s tireless attempts to disrupt racism and sexism, while capturing the oppression Black women faced in her day, echo through many of Beyoncé’s lyrics, visual images, and performances, exceedingly so as her career continues to evolve. Both Beyoncé and Truth contribute to a Black feminist history and trajectory; they just utilize different contexts and strategies. Historical circumstances certainly differ—Truth worked adamantly against the system of her time from an outside position after escaping slavery; Beyoncé works firmly within a capitalist apparatus, but it’s possible to find critical commentary on that same system in a close analysis of her music. Both women also crafted public images for themselves divorced from their personal histories and private lives. And they are both examples of uncredited forms of education, of “Schoolin’ Life.” Education, intellect, and smarts are not just the domain of official institutions or the ivory tower in America; rather, knowledge can come from anywhere—life experience, struggle, political positioning. Truth wasn’t able to attend school as a young girl because she was enslaved; Beyoncé left official schooling as a girl to earn capital in the entertainment industry, having been primed for that career since before she could make the decision for herself. Both became powerful symbols for their respective times.

I still assign the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech in class, framing it as performance, not fact, and alongside more accurate snippets of Truth’s life as told by Painter and through Truth’s own Narrative. Just as conversations around celebrity gossip today can teach audiences about what is prized and valued in society, Truth’s speech still has the power to pose questions about how and why Truth is remembered as she is, as well as to question what gets forgotten in doing so. The speech and the larger work of Sojourner Truth is a useful historical entry point into the intersection of race and gender—intersectionality long before it was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw. I also ask students to think about the “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech as anticapitalist critique, to which the syllabus returns in more detail later in the semester. Yes, the erasure of Black womanhood specifically is at the heart of the repeated “Ain’t I a woman?” query, but Truth maintained that that erasure was fueled through the economics of slavery via capitalism. The speech focuses on Black women’s exclusion, given the work they were often required to do, from the separate spheres white women were afforded. “Look at me! Look at my arm! I have ploughed, and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me. And ain’t I a woman?” Truth allegedly exclaimed. She exposed the fact that gender categories and expectations have been used as racist tools throughout history to separate white and Black as well as male and female, all for capitalist gain. Profits over people. Truth positioned work done as an enslaved Black woman—forced planting, ploughing—as a site to uncover the ways intersecting gender, racial, and sexual differences, taken for granted as innate, are actually created and preserved by those reaping the profits.

Beyoncé approaches similar territory by deconstructing what it means to be a diva more than one hundred and fifty years later, performing as her alter ego Sasha Fierce. The lyrics of “Diva” highlight work, albeit in different contexts, to unapologetically demand an answer to Truth’s iconic query. Beyoncé simultaneously updates, inflects, and rephrases it with her own unique, contemporary spin, and it’s no longer a rhetorical question with performative flourish—it’s a merciless, defiant assertion. By thinking about Sojourner Truth alongside Beyoncé, “Ain’t I a woman?” slides powerfully into “I’m-a a diva.” And Beyoncé’s diva takes no prisoners.

Ain’t I a Diva?

In today’s vernacular, embracing your inner (or outer) diva is not a de facto positive attribute. But that’s exactly the reframing Beyoncé attempts in the 2008 song from I Am … Sasha Fierce. The word “diva” entered English from the Italian for “female deity” in the late nineteenth century and typically referenced the most coveted female role in opera, achieved only after years of dedication to honing talent and craft. However, race, gender, and sexuality all carve out aspects of today’s definition of diva, heavily informed by pop culture. A string of popular performance specials on the cable network VH1, beginning in 1998 and airing as recently as 2016, sought to reclaim and celebrate divas, but the term is still often colloquially (mis)understood as a woman who is bossy, difficult, or entitled. Today’s pop culture divas may demand attention, but often for notorious, ignoble reasons that have nothing to do with talent. Diva has racial and queer connotations too—an intersectional position all its own. RuPaul’s Drag Race has celebrated drag divas, campy cattiness overflowing, for mainstream audiences since 2009. Sasha Fierce’s diva, comparable to Sojourner Truth’s “woman,” incorporates these multiple pieces and enacts a complex critique of power from categories often seen as powerless. And like Truth, Beyoncé also hints at the fact that capitalism creates racial, gender, and sexual difference to begin with in “Diva”—while performing her own queer drag parody.

In the opening shot of the music video, Beyoncé shares exactly the definition of diva she wants understood as central to her song and Sasha Fierce performance:

di•va

\´dē-vǝ\

plural divas or di•ve

NOUN

1 a successful and glamorous female performer or personality <a fashion diva>;

2 especially : a female singer who has achieved popularity <pop diva>

The definition is altered slightly from Merriam-Webster’s, and offering it as an introductory title screen indicates those changes must be significant. She completely leaves out Merriam-Webster’s first definition of “prima donna” and then alters the second definition somewhat, splitting it in two to fit her purposes. While the dictionary’s definition begins, “a usually successful and glamorous female performer or personality” (my emphasis), Beyoncé insists on the success and glamour of her diva, and thus suggests audiences consider the various costs of that success. Under capitalism, success does not always follow talent, but one’s success is often built on the exploitation or erasure of others, just as the category and separate sphere of womanhood was built off the labor of Black women. Some snide criticism delivered by Sasha Fierce, speaking from an outsider position to expose difficult truths.

Beyoncé then importantly stresses achievement in her diva, as opposed to tacit popularity—the achievement and work involved in becoming a diva—whereas the dictionary merely deems the diva “a popular female singer.” Anyone can be popular and not deserve it. Capitalism especially doesn’t care about talent or merit, only profit and hype (popularity). Turn on the radio today and you’re bound to see this principle in action. In addition to deconstructing the success and glamour Sasha Fierce invokes in the first part of the definition, Beyoncé is throwing specific shade at those who may receive notoriety or fame without putting in hard work, or have no real talent or skill—those who benefit off the system at the expense of others. In a 2015 Made in America performance of “Diva,” Beyoncé sampled words by mixed martial arts fighter Ronda Rousey, naming the one who profits while not studying and cultivating their talent or working hard to achieve their success, in heightened distinction to her redefined diva, a “do-nothing bitch.”

When Beyoncé calls out so-called divas for their lax work ethic, there exists a surprising reflection of the way Audre Lorde constantly confronted her various audiences, letting them know that she was vigilantly doing the difficult work of challenging all forms of oppression on a daily basis, and demanding to know if they were doing their own version of that work. In “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action,” Lorde states, “Perhaps for some of you here today, I am the face of one of your fears. Because I am woman, because I am Black, because I am lesbian, because I am myself—a Black woman warrior poet doing my work—come to ask you, are you doing yours?” Beyoncé is astutely mirroring Lorde from her own vantage point and confronting her audience with the various ways that the word “work” works. Audre Lorde and Beyoncé both hold themselves to the highest standard, and demand a high standard of their audience. It’s easy to simply equate work here with achievements within a capitalist enterprise. And that traditional sense of work is certainly central, evidenced by lyrics that make “getting paid” a priority, but money doesn’t always follow the work. Some profit from exploitation of others’ work, even getting paid means more than cash in pocket in a Beyoncé performance. To stop there would be to abandon the power of the connection with Lorde and the full critique Beyoncé levels.

In Life Is But a Dream, Beyoncé offers an analysis of money as power, not for individual gain but for its revolutionary potential to affect change for bette...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Ain’t I a Diva?

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword: “Aren’t I an Archive?”

- Introduction: Schoolin’ Life

- 1 Ain’t I a Diva?

- Past

- Present

- Future

- Epilogue: Let’s Start Over

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Master Syllabus

- Appendix B: More Information

- About the Author

- About Feminist Press

- Also Available from Feminist Press