![]()

1

Decoding Ideology

Nationalism, Communalism, and Its Critiques

The intentional homogenization of national identity irrespective of India’s diversity led to a violent reorganization of people and places based on religion, caste, region, and language. The demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992, was a critical highpoint of sorts that culminated in the growing tension between the Hindus and other religious minorities including Muslims. In a way, it communalized India on religious lines leading to a reimagining of India as a Hindu nation. Events similar in magnitude such as the Gujarat riots (2002) and Muzaffarnagar riots (2013) further deepened the crisis. Against such a background, communalism, hate-pogroms, and fundamentalism became a recurrent theme in documentary films produced especially after the 1980s. Unlike the commercial cinema which underplayed sensitive themes such as communalism and religious fundamentalism or the Films Division (FD) films which made ultra-nationalistic films, many independent documentary filmmakers such as Anand Patwardhan, Amar Kanwar, Rakesh Sharma, Gopal Menon, Nakul Singh Sawhney, and Kasturi Basu, through resorting to different aesthetic styles (such as observational, interactive, essay, and self-reflexive style) of filmmaking, probed the anatomy of hate politics and communal violence. Furthermore, these filmmakers, for instance Tapan Bose, boldly expose systemic violence, human rights violations, and the fundamentalist ideologies that shape contemporary India. In critically examining the nation-state and its apparatus which invests on the praxis of jingoism, religious, and cultural fundamentalism, these filmmakers also uncover the inner workings of the ideologies and everyday programs of the authoritarian state that fuel hatred and fear. In doing so, their documentaries function as repositories of social and cultural memories that get consciously erased by the influential forces and institutionalized history. The following interviews throw light on the workings of communalism, divisive politics, production of religious alterities, and extremist ideologies in contemporary India.

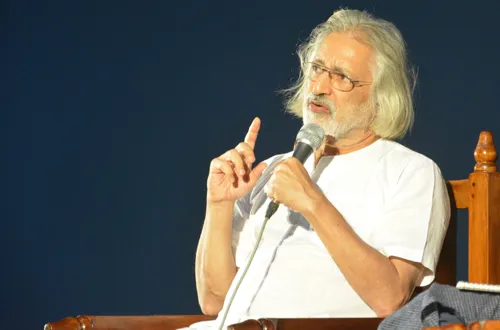

Anand Patwardhan

Deemed as the father of independent documentary films in India, Anand Patwardhan is a distinguished voice in postcolonial Indian cinema. Born in Bombay in 1950, he received a scholarship for a BA program at Brandeis University, USA. During that period, he was imprisoned twice for anti–Vietnam War protests and also worked for six months as a volunteer with the Cesar Chavez-led United Farmworkers Union (UFW). He returned to India to work in Kishore Bharati, a voluntary rural development and education project in Madhya Pradesh,1 and later joined the Bihar Movement,2 which eventually led to the declaration of Emergency in 1975. Having made his first documentary Waves of Revolution in this period, he had to smuggle it abroad in parts during the Emergency. Anand was able to get a teaching assistantship to do his master’s in arts from McGill University, Canada, where he put his film back together to screen as part of the anti-Emergency movement. Partly inspired by the New Latin American cinema, his films since the 1970s have concentrated on sociopolitical and human rights issues in India, including the rise of religious sectarianism. Waves of Revolution and Prisoners of Conscience, his early documentaries on the Emergency (from 1975 to 1977) paved the way for the introduction of the independent political documentary films in India. His films boldly explore religious fundamentalism (Ram Ke Naam) and sectarian violence and caste-based discriminations (Jai Bhim Comrade). As a self-proclaimed secular rationalist, he is one of the fiercest critics of Hindutva ideology and its attendant practices in India. In a career spreading over four decades, he has produced several documentary films including Father, Son and Holy War, which was adjudged as one of the fifty most memorable international documentaries of all time by Dox. As an opponent of religious extremism, his films are uncompromising cinematic critiques of an oppressive nation-state and its jingoistic policies. They challenge the sectarian violence, caste-based discrimination, and patriarchal determinism that plague contemporary India in the guise of “nationalism.”

Figure 1 Image Credit: Rajesh James.

Selected Filmography

Reason (2018)

Jai Bhim Comrade (2012)

War and Peace (2002)

A Narmada Diary (1995)

Father, Son and Holy War (trans. Pitra, Putra aur Dharmayuddha) (1995)

Ram Ke Naam (trans. In the Name of God) (1992)

In Memory of Friends (1990)

Hamara Shahar (trans. Bombay Our City) (1985)

Prisoners of Conscience (1978)

Waves of Revolution (1974)

What made you a documentary filmmaker? How did your love for the documentary medium begin?

I did my BA in English at Bombay University in 1970. Then I got a scholarship to do another BA in sociology at Bra ndeis University, USA. I returned to India in 1972 and worked for a village project for a few years in Madhya Pradesh, mainly doing social and educational work. But the pace of work was very slow, and I was getting frustrated. At that moment the Bihar Movement had begun. It was a nonviolent student movement, which turned into a mass movement against corruption and other social evils like dowry and caste. I went there to see what was happening and got involved in it. As a part of the movement, I was asked to take photographs on a particular day (November 4, 1974) when the police were expected to use violence to curb a mass demonstration. I went to Delhi to borrow a camera but instead of a still camera I found a friend Rajiv Jain who had a Super 8 camera. The two of us came back with his Super 8 camera and my 8 mm camera that had belonged to my late grandfather. With this low-grade equipment, we filmed that day’s demonstration, which was pretty violent. And then, I thought I could do something more with it, because Super 8 was a format where you shoot on reversal film, not on a negative. That is, every time you project the film, it gets scratched, or breaks, or you could lose it altogether. So we blew it up to 16 mm. As I didn’t have money, we projected it onto a screen and refilmed it with a 16 mm camera. The projector and camera were not in perfect sync so we got a strobe-like effect but it looked dramatic. Then I invited another friend, Pradeep Krishen, to join me as he had just bought a second-hand, three-turret Bell & Howell 16 mm camera. You needed to actually hand-crank it, to shoot for less than one minute at a time. So, with that equipment, we went back and filmed in Bihar. None of the sound was synchronized. We had a cassette tape recorder to record voice at the same time, but it was never accurately matched. The film stock itself was outdated, old color footage that Shyam Benegal3 was going to throw away but someone told us that it may still work as black and white. So, there were all these technical problems when Waves of Revolution was made. By the time the film was completed, the Emergency was declared, and most of the people I had filmed were in jail. We couldn’t show the film openly because of the fear of ending up in jail but held a few clandestine screenings for friends. I then cut one print of the thirty-minute film into four smaller segments and smuggled these out through friends going abroad. A few months later I reached Montreal, Canada, where I got a teaching assistantship at the McGill University to pursue an MA degree. I then put the segments together and we showed it at various universities abroad as a protest against the Emergency. When the Emergency ended in 1977, I came back to India. I found that all political prisoners had not yet been released, though the Janata Party had come to power saying that they would release all prisoners. So, I continued making a film on the condition of prisoners, during, before, and after the Emergency. That became Prisoners of Conscience. Over time, I eventually ended up becoming a filmmaker, although it was not my original plan.

What is the process of your documentary practice?

That is quite vague. Take, for instance, the films I ended up doing about communal violence. They started from the general fact that communal feelings were being cynically manipulated by political forces. More and more in the mid-1980s, we saw examples of communal riots. I wanted to intervene, but didn’t know how. When the Khalistan movement began, I was looking for a way to intervene, especially after the 1984 anti-Sikh massacre. As many as 3,000 Sikhs were killed on the streets of Delhi after the assassination of Indira Gandhi.4 I went to the camps where refugees from Sikh families were camped in front of the Rashtrapati Bhavan5 in the Boat Club. Those days, people could go and demonstrate there; now you can’t. I interviewed some of the widows and mothers who had lost their loved ones. I still didn’t know what to do next, as it was a very depressing moment to see the horrific incidents that had happened. People were already forgetting it, pretending it hadn’t happened. I wanted to go to Punjab6 to do something useful, to fight the polarization that was taking place there. I finally got my opportunity when I met a group of Hindus and Sikhs who were carrying forward the message of communal harmony as spoken and written by the legendary martyr of India’s freedom struggle, Bhagat Singh.7 They were carrying this message going from village to village in Punjab. I followed them. Typically, I end up doing my research while on the job. I don’t usually first research something and then decide to make a film. I start making a film instinctively and then study the subject more in depth. So, I read about Bhagat Singh’s writings and was amazed at this person. At the age of twenty-three, Bhagat Singh had already done enormous reading. His handwritten diary shows that he had read everything from Wordsworth, Mark Twain, Gandhiji, Tagore, Marx, Engels, and others. His diary had quotations from all he had read while in prison. From prison he also wrote a booklet, Why I Am an Atheist? That became a kind of backbone for the film—Bhagat Singh’s message at a time of communal violence between Hindus and Sikhs. The structure and storyline and everything emerged from the process, and was not prethought.

I never have a script; I don’t know exactly what I am doing while I am doing it. I have my own camera and am on call. I follow my intuition, and there are plenty of things I shoot that don’t end up in any film. They become a kind of a personal archive. But eventually, when I am following a particular issue related to a particular subject, after a while I start seeing the patterns in what I have shot, by watching it again and again and seeing how some aspects interconnect. The film structure then evolves from the editing process.

Still 1 Anand Patwardhan during the filming of Waves of Revolution. Image Credit: Raghu Rai.

War and Peace is about the trajectory of a nation that achieved Independence through non-violent means to a country that is strengthened by nuclear weapons? Do you think it’s only people’s security and interests that is behind such a shift? Why do you think the Gandhian notion of nonviolence is still valid?

Nuclear weapons have made not just India but the whole world insecure. Today, the world is once again on the brink with a mad Korean and a mad American both with their fingers on the button. War and Peace like all my films was not scripted but emerged from what I observed over four years, shooting in four countries. Of course, my own influences, which are a free-flowing mixture of Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Marx, impact what and how I ...