- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

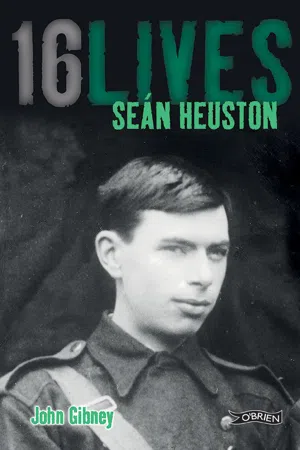

Seán Heuston was an Irish rebel and member of Fianna Éireann who took part in the Easter Rising of 1916. With The Volunteers, he held the Mendicity Institute on the River Liffey for over two days. He was executed by firing squad on May 8 in Kilmainham Jail. This book, part of the '16 lives' series, is a fascinating and moving account of his life leading up to and during these events.

It follows his life, from his birth in Dublin, to his time as a railway clerk in Limerick. Finally it outlines his move back to Dublin, his joining The Volunteers, the Easter Rising, his imprisonment and execution. This book is a fascinating and moving insight into a man who sacrificed his life for his country.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sean Heuston by John Gibney, Lorcan Collins (Editor) in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1:

Heuston’s Dublin

1891-1911

Seán Heuston was born John Joseph Heuston on 21 February 1891 at 24 Lower Gloucester Street (now Seán MacDermott Street), the son of John Heuston, a clerk, and his wife Maria (née McDonald).7 John Heuston – Seán’s father – was born on 10 August 1865 at 65 Great Strand Street, the son of John Heuston, a porter, and his wife Mary Anne (née Clarke). Heuston’s mother, Maria was born on 29 December 1867 at 61 Marlborough Street, the daughter of Michael McDonnell, a bedroom porter, and his wife Mary (née McGrath). The civil authorities seem to have confused the surname of Heuston’s mother; even on the birth certificate of her youngest child, Michael, born in 1897, her maiden name was given as ‘McDonnell’. But such glitches were not unknown; it seems likely that this was indeed the Maria McDonald who had been baptised in the Pro-Cathedral (also on Marlborough Street) on 31 December 1866 and who married John Heuston in the same venue on 22 January 1888.8 Seán Heuston’s roots lay in Dublin’s north inner city.

Of the sixteen men executed after the Easter Rising, six – Heuston, Roger Casement, Michael Mallin, the Pearse brothers and Joseph Mary Plunkett – were from Dublin. With the possible exception of Mallin, Heuston came from the humblest background of them all. His father, John, was a clerk, though the precise details of his job and his background remain obscure, as do many of the details of Heuston’s early life. Clerical jobs in the capital were reasonably meritocratic, insofar as the closed shops operating in other professions and trades rarely applied to them. By the end of the nineteenth-century there was a slow but sure increase in the numbers of clerks from working-class backgrounds; a small indicator that social mobility wasn’t unheard of in Victorian Dublin. But the key criterion for clerical jobs was an education. This meant that they were effectively restricted to families who could afford to keep a child in education, and this placed them beyond the reach of the vast ranks of the unskilled labouring poor.9 Heuston’s father was lucky in one sense, but the address at which the family lived in 1891 points very strongly towards the world from which they came and from which, presumably, they were trying to escape.

At the time of their marriage Heuston’s father lived at 12 North James’s Street and his mother at 34 Jervis Street. They began their family at 24 Gloucester Street, on the fringes of the vast Gardiner estate north of the River Liffey. This had been developed by the Gardiner family from the 1720s onwards and its centrepiece was Sackville Street and Gardiner’s Mall, both of which would later be merged into Sackville – O’Connell – Street. The estate was one of the most prestigious residential areas of what was, in the eighteenth-century, a city dominated by the Protestant aristocracy known to history as the ‘ascendancy’.10 Dublin had been a centre of administration, education, the judicial system and trade for centuries; its reworking as a ‘Protestant’ capital city during the eighteenth-century went hand in hand with an extraordinary growth. Many of its public buildings and much of the streetscape that its inhabitants were still familiar with in the early twentieth-century dated from that era; by circa 1800 Dublin’s population had tripled within a century to approximately 182,000. Even aside from the presence of the aristocracy (who accounted for a large chunk of the city’s economy), eighteenth-century Dublin had become a significant manufacturing centre and a major distribution point for imported goods. Its cultural and political influence was unmatched on the island and the description of Dublin as the apocryphal ‘second city’ of the British Empire makes a great deal of sense in relation to the eighteenth-century. Yet the same cannot be said of the nineteenth.

Dublin has presented a number of faces to the world, but two of the best known go hand in hand, as the splendour of the eighteenth century gave way to the squalor of the nineteenth. There were various reasons for this transition, but the symbolic dividing line was usually taken to be the Act of Union of 1800. The formal integration of the Irish parliament with its British counterpart meant that Ireland’s ruling elites began to leapfrog Dublin en route to London, and the aristocracy for whom much of the city was remodelled slowly but surely abandoned it. This was not the only reason for Dublin’s decline, but it was a very visible mark of it. Take, for example, Aldborough House, located a few hundred yards from Heuston’s eventual birthplace in the north of the city. Completed in 1799 for John Stratford, second earl of Aldborough (who died in 1801), it was apparently meant to rival Leinster House on the southern side of the River Liffey, but ironically, was the last aristocratic mansion to be built anywhere in the city. It later became a barracks, which helped to sustain the large and notorious red light district that sprang up in the streets around Heuston’s birthplace: ‘Monto’.

The Act of Union was indeed a landmark in the history of both Ireland and its capital, with Dublin now becoming a regional capital within the new United Kingdom. Aldborough House may have been the last of its kind, but other building projects continued after 1800 (though not on an eighteenth-century scale): the GPO (1818), King’s Inns (1820), the commissioners for Education on Marlborough Street (1835-61) and the prisons at Arbour Hill (1848) and Mountjoy (1850), to name a few that formed a backdrop to Heuston’s life. The city that he grew up in had not come to a shuddering halt at the turn of the nineteenth-century: Dublin continued to grow after the union. But the rate at which it did so was much reduced and the size of its population gives an indication of its decline: in 1891, the year of Heuston’s birth, the population was only 245,000. Even aside from the loss of the aristocracy and the parliament, Dublin embarked upon a downward spiral in the decades after 1800, as its traditional industries (such as textile manufacturing) were whittled away. Within the newly-expanded United Kingdom, Dublin’s primary function was as a transit point for the export of food and people and the importation of British goods: a perpetual motion driven by the imperatives of Britain’s industrial centres. The vast bulk of its trade was with the rest of the UK rather than the rest of the world; the docks that lay so close to Heuston’s place of birth were in no way comparable to the great docklands of Britain. Dublin was not an industrial city; other than food processing it lacked labour-intensive industries, and was in no position to compete with other major UK cities like Birmingham, Glasgow, Liverpool or Manchester.

There were, however, some shards of light amidst the gloom. By the end of the nineteenth century Dublin had acquired some important constellations of new buildings: the museums clustered around Leinster House, new churches, the banks that had grown around College Green and the massive commercial edifice of the Guinness brewery. Likewise, by 1891 its infrastructure was much improved, with new water supplies and a new tram network. The railway boom of the later nineteenth century had given Dublin a ring of new stations around its centre (and later gave Seán Heuston a job). But this was all somewhat piecemeal. Dublin did not experience the wholesale rebuilding that characterised many other capital or industrial cities. What it did witness was urban decline and a widening gap between rich and poor in a de-industrialised city. In the mid-nineteenth century, this economic stagnation was accompanied by one of the most significant social developments in the city’s history, as the emerging Catholic (and remaining Protestant) middle classes abandoned the city between the canals and relocated to new townships such as Clontarf and Rathmines. In the vacuum left behind, slums and tenements flourished, and this had major implications for many of those who continued to live within the city proper. Dubliners were perhaps the least likely of Irish people to choose emigration, but if poverty and deprivation were reasons to emigrate, than Dubliners had more reason than most.

The poverty that was seen to characterise Dublin by the late nineteenth century was a product of decline. It had long been noted as a feature of urban life, but the problem had got worse after the union, as the eighteenth-century estates declined into slums characterised by disease, disrepair, malnutrition and poor sanitation. Over the nineteenth-century, poverty became a more visible problem as it colonised previously-fashionable areas left behind by both the ascendancy and the middle classes who had followed them, most notably the old Gardiner estate, which witnessed a remarkable collapse in its social composition from the 1850s onwards. Gloucester Street was a perfect example of a street that had declined: as early as 1885 one house on the street had been used as an example of urban squalor for the benefit of a public inquiry and by 1899 some 55 per cent of its houses were either tenements, or were derelict.11

The social and economic structure of Dublin did little to soften these blows. The population of the greater Dublin area stood at 404,000 in 1911; an increase from 317,000 in 1851, which was demographically unique in Ireland. But Dublin’s patterns of employment were also distinctive. In 1841 as many as 33 per cent of the male workforce was employed in manufacturing; that proportion had come down to 20 per cent by 1911. As the city continued to shed its remaining industries while its population continued to expand, casual and unskilled labour became increasingly important: by 1911 one in five of all male workers in the city could be categorised thus. The poor had to take whatever work they could get and this posed barriers to their advancement: clerical work, for instance, required an education that was beyond the reach of many tenement dwellers, as the necessity for casual employment got in the way. Skilled labour tended to stay within family networks and there was competition for casual labour from immigrants from the countryside. The more secure labouring occupations – policing, government, corporation, brewing, tramways and railways – were disproportionately occupied by migrants from elsewhere in Ireland. In other words, Dublin’s poorer classes were squeezed even further into the area of casual, unskilled labour. Given their address in 1891, the Heustons were lucky to have a regular breadwinner, however modest. In a city starved of industry, prospects for improvement became more limited the further down the social scale one was. And Gloucester Street was very far down that scale.

But the family managed to move away from there. By 8 June 1897 – the date of birth of their youngest child, Michael – the Heustons were living at 34 Jervis Street, another slum area in the north inner city.12 Thirty-two people had been killed by tuberculosis on Gloucester Street between 1894 and 1897: reason enough to move a small family, perhaps, but we cannot be sure.13 According to the census of April 1901 there were four families in 34 Jervis Street, one of the smaller dwellings on a street with over nine hundred inhabitants. Seán Heuston’s family occupied three rooms in what was categorised as both a first-class dwelling and a tenement. There was, however, one notable absentee in 1901: his father. John and Maria Heuston had four children. The eldest was Mary, aged twelve in 1901, followed by John – Seán – aged ten, Teresa, aged eight and Michael, aged three. But John Heuston had left the family home at some point after Michael’s birth and it would appear that the family had moved in with Maria’s two unmarried sisters: Teresa McDonald, thirty-two, who was recorded as the head of the family and who worked as an envelope maker, and Brigid, thirty, who worked as a vest maker. Between that and the fact that their father was absent, it is possible that they had fallen on hard times and that John Heuston had left his wife and children in search of work. But we cannot be certain.

Like their counterparts in so many times and places, the urban poor of Victorian Dublin left relatively few traces behind them, except insofar as they were noticed by officialdom. The Heuston family is no exception. The reasons why John Heuston left the family home remain unknown, but at the time of his eldest son’s death, in May 1916, he was living in London. A letter that Seán wrote to his father on the eve of his execution hinted at an estrangement; it stated that he had not seen his father for many years and had become the main breadwinner for the family. Given his youth, it seems likely that Seán had not seen his father since childhood and, given the circumstances that he wrote of, his father may well have left to seek work elsewhere. Yet the fact that Heuston’s mother and father were in a position to contact one another after their eldest son’s execution suggests that family affairs were not automatically acrimonious.

At this remove it is impossible to penetrate the inner workings of Seán Heuston’s family. But what we can do is take note of the appalling poverty and squalor of the areas in which he was born and raised, and to which he could not have been oblivious. The decayed poverty of places such as Gloucester Street and Jervis Street was evident in photographic evidence presented to the 1913 inquiry into Dublin’s tenement problem, undertaken after the collapse of two tenement houses on Church Street in 1913; another place that Heuston would come, in time, to be very familiar with.14 But by then his family had left Jervis Street as well as Gloucester Street and Heuston no longer resided in the city of his birth.

Chapter 2:

Heuston’s Ireland

Heuston was born in 1891: the same year that the Home Rule leader Charles Stewart Parnell died, though the cause Parnell espoused continued to dominate Irish nationalism over the course of Heuston’s relatively short life. Heuston died for his involvement in a separatist uprising, but the separatism that he and his colleagues adhered to had been on the fringe of Irish politics in the years after 1891. Indeed, it had been on the fringes for years before then. In 1891 the Irish Republican Brotherhoo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- 16LIVES Timeline

- 16LIVESMAP

- 16LIVES - Series Introduction

- CONTENTS

- A Note on Conventions

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Heuston’s Dublin, 1891-1911

- Chapter 2: Heuston’s Ireland

- Chapter 3: Heuston and Na Fianna

- Chapter 4: Heuston’s Dublin, 1913-1916

- Chapter 5: The Prelude to the Rising

- Chapter 6: The Mendicity Institution

- Chapter 7: Heuston’s Fort

- Chapter 8: Capture and Courtmartial

- Chapter 9: From Sentence to Execution

- Chapter 10: Doomed Youth?

- APPENDIX 1

- APPENDIX 2

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- NOTES

- Index

- Plates

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Other Books