- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

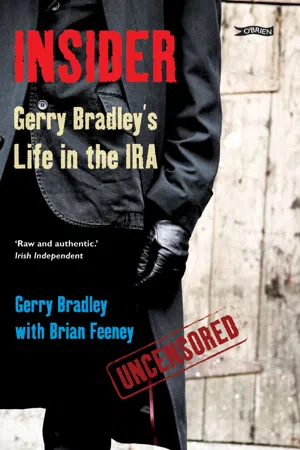

About this book

BRADLEY SPEAKS OUT FOR THE FIRST TIME – WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE IRA

The IRA was Gerry Bradley's life. His sole interest was in 'ops' – carrying out on-the-ground war. Inspired, initially, to defend his home place against Loyalist threats, he became one of the most senior operators in Belfast IRA. When things turned political, there seemed to be no place for his kind of activism.

THE INSIDE STORY BY A SENIOR IRA MAN

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Insider by Gerry Bradley,Brian Feeney in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781847174550Edition

21

BAPTISM OF FIRE

Bradley vividly recalls the feeling of shock and dismay he shared with all the other onlookers when they saw that the van was carrying pick-axe handles. The IRA had no guns to hand out.

Unity Flats was an estate of social housing near the centre of Belfast whose frontage stretched 350 metres from the bottom of the Shankill Road to Clifton Street. British soldiers knew the district as a hotbed of IRA support. For the soldiers, the flats were a concrete maze of stairways, connecting galleries – or balconies, as the residents called them – dead-ends and dangerous open spaces overlooked by a score of firing positions. Soldiers could be shot at from windows, galleries, doorways, from ‘wash-houses’ built of latticework brick, where washing often hung at the end of each row of flats, or from the flat roofs of the housing complex. Blast bombs, concrete blocks, bottles, bricks or pieces of metal could be hurled from the galleries as soldiers sought cover to avoid the open ground between blocks of flats. Troops always entered the complex in strength, covering each other and trying to move about quickly and unpredictably. In the 1970s, merely driving past Unity Flats in an army Land Rover often invited a fusillade of shots.

The flats had been built to replace nineteenth-century slum housing in the district known as Carrick Hill, where 1,314 tiny houses had sat on thirty-one acres. The area was designated a redevelopment area in 1958 but after the inevitable public inquiry and other delays, clearance did not begin until 1963. The first new home was ready for occupation in May 1967.

When the modern IRA was established in 1970, there were two hundred dwellings in the Unity Flats complex, a classic 1960s development of twenty blocks of medium-rise flats and two-storey maisonettes. Ultimately, Unity Flats would have 315 dwellings, but further planned expansion had been aborted by the outbreak of civil strife in 1969, which led to repeated attacks from the nearby ultra-Unionist Shankill Road, whose residents had always strongly objected to the new complex rising on their doorstep.

How and why did such a small district produce a large number of men and women prepared to risk their lives, to kill, to shoot and bomb, to go to jail for lengthy periods? Why would people living in brand new modern housing become embroiled in such activities? What circumstances changed their lives from a humdrum daily existence in summer 1969 to a frenetic, lethal, high-octane, cat-and-mouse conflict six months later? What did they think they were doing and why?

Some people claim that the name of the development, Unity Flats, was chosen to symbolise the uniting of two communities, Catholic Carrick Hill and Protestant Shankill, which had been at loggerheads for generations. Others say the name came from Unity Street, which originally ran through the Carrick Hill district. Whatever about aspirations to unite the two communities, the fact is that Carrick Hill was mainly Catholic and it was families from Carrick Hill who had been temporarily cleared out so that the new flats could be built. Since that was so, it would be the same Catholic families who would be rehoused in Unity Flats as each phase was completed. There were never more than a couple of dozen Protestant families living in Unity, and after the August 1969 disturbances, twenty of them moved out. By February 1970, only two Protestant families remained.

In 1969, the blocks of Unity Flats constructed to that date formed a rough quadrilateral, with a dent in one corner where it abutted onto the Shankill at Peter’s Hill. The base of the quadrilateral, Upper Library Street, 350 metres long, ran from the Shankill Road to Clifton Street. The narrowest side, facing Peter’s Hill at the bottom of the Shankill Road, was 60 metres long. The ‘safest’ side, because it faced the nationalist New Lodge district along Clifton Street, was 200 metres long. The most dangerous side, the ‘front line’ so to speak, because it faced the Shankill district across waste ground cleared of slum housing, stretched for a hazardous 400 metres.

This large expanse of waste ground lay ready for the next phase of building. Beyond it stood several streets of partially demolished and derelict housing, the western edge of the nineteenth-century slums of Carrick Hill cleared of their inhabitants. This scene of dilapidation would become a battleground throughout the 1970s between attackers from the Shankill and the new residents of Unity Flats. The empty houses and waste ground provided abundant ready-to-hand missiles: stones, broken bricks, ironmongery and other debris strewn thick on the ground.

By dint of hoisting the people into two- and three-storey flats, modern housing design in the 1960s enabled planners to cram over a thousand men, women and children into an area of less than nine acres, which became Unity Flats. The building materials used in the flats were cheap: the walls were prefabricated and prone to penetrating damp; the roofs were flat, thereby saving the cost of the joists and rafters and tiles that pitched roofs required, but guaranteeing leaks in Belfast’s damp, drizzly weather. In a few years, blocked internal downspouts from the roofs would cause great patches of damp on inside walls and drips from ceilings.

Nevertheless, the new homes had modern electrical wiring, heating, toilets and bathrooms, and hot and cold running water in purpose-built kitchens, none of which the people in the nearby Shankill had. Who was to know that the flats would be so horrible to live in and would start to fall apart in less than a decade? They were spanking new and brightly painted, and as more and more of them were completed and the residents moved in, it looked as if block after block of Unity Flats, with its growing Catholic population, was marching up into the Shankill, while there was no sign of any new houses for Protestants.

As soon as the first residents moved into their new homes in 1967, they were attacked. The most vulnerable flats were those called Unity Walk, fronting the Shankill Road at Peter’s Hill. Weekends were worst. Supporters of Linfield football club, the North of Ireland’s most aggressively Protestant team, would throw bottles and stones and metal bolts at the flats as they returned from matches on a Saturday. On Friday and Saturday nights, drink-fuelled groups of Shankill Road men walking home from the city centre and others emerging from the nearby Naval Club, used Unity Walk for target practice, and intimidated and sometimes assaulted residents foolhardy enough to be in the open.

Paddy Kennedy, the Republican Labour MP for the district, raised the matter of these attacks in the Stormont parliament in March 1969. Windows were broken so often in flats facing the Shankill Road that people gave up replacing them and left them boarded up, he reported. He said that although the numbers of Linfield supporters coming along the Shankill Road were large enough to constitute unlawful assemblies, and that drunks coming from the Naval Club were regularly committing offences, there was no police protection afforded to the people in Unity.

All this was a small foretaste of what was to come. The frequency and ferocity of attacks on the flats increased in direct proportion to the rise in tension across Northern Ireland in 1969. Unionists, generally, had been aggrieved by the demands of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, its controversial marches, and the pressure the British government at Westminster was exerting on Stormont to bring in reforms in voting and housing that would benefit the North’s Catholic population – exactly the sort of people who were living in newly-built accommodation in Unity Flats.

As 1969 began, a snap Stormont election was called for February, leading to a bitterly sectarian campaign in which Reverend Ian Paisley played a major role. In March, there was a startling Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) bombing campaign at reservoirs, which the UVF did not admit and which most unionists therefore believed was the work of the IRA. Water supplies to Belfast and County Down were disrupted. In April, the Stormont Prime Minister Terence O’Neill resigned, as he later said, ‘literally blown out of office by the UVF’.

Unity Flats provided a readily available focus for the resentments of anti-Catholic gangs from the Shankill. These fears and resentments of people on the Shankill Road were channelled into aggression by the activities and speeches of local leaders, including the Stormont MP Johnny McQuade, a coarse, foul-mouthed, barely literate former British soldier, ex-boxer and ex-docker.

Most sinister was John McKeague. McKeague was a paedophile whose sexual proclivities had come to the notice of the police. In 1970, he was one of those charged with the 1969 waterworks bombings but acquitted, though in later years he bragged about his involvement. He was rabidly anti-Catholic, a dangerous rabble-rouser who formed the Shankill Defence Association (SDA) in 1969, a body that would play a violent role in the events of August 1969, and in 1971 merged with the murderous Ulster Defence Association (UDA), responsible for the deaths of 431 people over the period of the troubles. In 1969, the SDA was about three hundred strong. McKeague would go on to found the Red Hand Commando in 1972, a small group of killers linked to the UVF.

Matters came to a head for Unity Flats in the summer of 1969 as the Orange ‘marching season’ gathered steam. There are two distinct and contrasting views of what happened in July and August 1969. One is the experience of the people living in Unity Flats. The other is provided by the Scarman Report, a judicial inquiry into the disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 by Mr Justice Leslie Scarman, a senior English High Court judge.

Here, first, is a condensed version of the official account of events, relying heavily on the Scarman Report.

There had been minor disturbances on the evening of 12 July as Orange bands returned towards the Shankill from the main gathering of Orangemen at ‘the Field’, as they called it, in south Belfast. To reach the Shankill, they had to pass Unity Flats. There was an exchange of missiles between crowds lining the Shankill Road to watch the marchers and bands and residents of Unity Flats, annoyed by twenty-four hours of noise and provocation, which began in the afternoon of 11 July. At one point, a section of the Orange crowd tried to gain entry to Unity Flats, but were repulsed by a small group of police who had taken up position at the Peter’s Hill entrance to the complex. It was pretty much par for the course on ‘the Twelfth’, the biggest day in the Orange calendar.

Three weeks later, a minor Orange parade, which at worst should have produced a repetition of the events of 12 July, with catcalls and minor stone-throwing, instead unexpectedly exploded into intense violence involving hundreds of rioters, and changed the lives of people in Unity Flats forever.

On Saturday, 2 August, a Junior Orange procession was due to parade along the Shankill into the city centre to catch the train to Bangor, a seaside resort on the north County Down coast. Long before the parade was due, crowds from the Shankill had filled the footpath opposite Unity Flats. Ostensibly, they were there to ensure safe passage for the children in the Junior Orange march. In fact, as the Scarman Tribunal found, many of the people assembled at Unity did not comprise an ordinary crowd. John McKeague and his Shankill Defence Association, 200-300 strong, had marched down the Shankill and taken up position on both sides of the road at Unity Flats. They were intent on trouble.

As soon as the parade passed, McKeague’s men, led by an individual carrying a Union Jack, launched an attack into Unity Flats. They were held off by the residents in serious hand-to-hand fighting, though several attackers did manage to get into the forecourt of the complex. Altogether, there seems to have been about a dozen policemen on duty at the entrances to the flats from the Shankill end. Residents later accused these policemen of joining in the attack with McKeague’s men. Sporadic fighting went on for most of the afternoon until about 4.30pm.

A dangerous rumour then circulated in the Shankill Road that the Junior Orange parade had been attacked on its way into Belfast past Unity Flats. As a result, crowds of people poured down the Shankill to wait for the parade’s return, expected some time before 7.00pm. An hour before the expected arrival of the Junior Orangemen, a huge crowd, estimated by the police to be upwards of three thousand, had filled the road at Unity Flats. Shortly after 6.00pm the crowd began to attack Unity Walk, but were repelled by police, who were now present in numbers. The attackers vented their frustration on the flats in what the Scarman Report described as ‘a continuous barrage’ of stones and other missiles, breaking every window facing Peter’s Hill. Others attacked the flats complex from the rear, across the waste ground from the lower Shankill Road and managed to gain access to the courtyards between the blocks of flats, where desperate fighting took place.

There was a real danger that the flats might be overrun and burnt by the Shankill crowd. In the course of the fighting, several residents were batoned by police, and one, sixty-one-year-old Patrick Corry, subsequently died from his injuries, namely three skull fractures. Fighting between police and residents, and between residents and would-be attackers advancing across the waste ground, continued for hours. It was only about 3.00am on 3 August, after police reinforcements had pushed the Shankill crowd away from Unity Flats, that quiet returned.

Yet, later that morning, Sunday, 3 August, a mob of 400-500 appeared again on Peter’s Hill opposite Unity Walk. This time there were 200 police with an armoured car and they dispersed the mob, only for them to regroup further up the Shankill and march back down again, led by McKeague’s SDA behind a Union Jack. The confrontation then became very serious and continued all day. The mob threw petrol bombs at the police and erected barricades which the armoured car easily broke through, but then gelignite bombs were thrown at the police. Finally, around 1.00am, the police managed to disperse the crowd after several baton charges.

The Scarman Report records that the Belfast Police Commissioner, at 4.45pm on Sunday, had asked for British army troops to be deployed since all police reserves had been committed. The commanding officer of the regiment in question, the Queen’s Regiment, consulted Brigade HQ in Northern Ireland only to be told by the chief of staff that committing troops was a political decision that could not be taken without approval from England. Responsibility for British troops was a matter for the British Secretary of State for Defence at Westminster, not the Stormont administration.

In any case, the RUC Inspector-General did not support the Commissioner’s request, partly, as he told Scarman, because of ‘the political angle that there were constitutional issues involved’. Nevertheless, the point is that a fortnight before the calamitous events in Derry and west Belfast which necessitated troops intervening, the circumstances on the ground between the Shankill and Unity Flats were so serious that senior figures were considering using troops, with all the implications that decision brought with it.

The residents’ perspective of the events of 2–4 August was entirely different from the measured tones of the Scarman Report, and the details differ markedly from the official version of events. To them, the inability of the police to protect them from the Shankill mobs was unforgivable, but not accidental. There was no question in the minds of the residents that the police and the invading mob from the Shankill formed common cause. Indeed, there are some passages in the Scarman Report itself that unintentionally support their view. Some instances of collusion between police and John McKeague’s SDA are recorded without comment or explanation in the Scarman Report, although Scarman roundly condemned McKeague elsewhere in his report. For example, Scarman did not seem to think the following incident incongruous:

Some of the Protestants managed to get into the courtyard [of Unity Flats] and fighting broke out between them and the residents. Mr McKeague was present in Upper Library Street during the incident. Evidence was given that he pointed out to the police a youth within the flats who was then set upon by Mr McKeague’s supporters and ultimately arrested by the police. (Par 9.6).

Why were police following any directions from McKeague? Why was McKeague allowed to be in Upper Library Street apparently directing operations? Why was he not arrested himself as, evidently, the instigator of the assault on Unity Flats and, indeed, on the particular youth in question here?

It seems that Mr Justice Scarman displayed many of the besetting sins of English judges appointed to enquire into matters in Northern Ireland. He could not imagine that in the RUC he was dealing with a partisan paramilitary unionist militia rather than with a civil police service on the English model. He could not contemplate the prospect that the police might, in fact, have taken sides against the beleaguered residents of Unity Flats. He could not accept that policemen joined the Shankill mob in throwing stones at people in Unity Flats. In short, Scarman tended to believe the police account of each incident.

As a result, he rejected the testimony of Unity Flats residents, sometimes without giving a reason. Mrs Austin, a woman who owned two shops in Unity Walk, testified that a number of police threw stones at the flats. She was even able to identify policemen involved. Scarman says: ‘After a full consideration of the evidence, we have come to the conclusion that [the police] did not throw stones. Mrs Austin was mistaken.’ But how could she have been mistaken? The police were in uniform, easily distinguishable from the mob. How could she have imagined the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Reviews

- Title Page

- DEDICATION

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- 1 : BAPTISM OF FIRE

- 2 : THE GENESIS OF G COMPANY

- 3 : MAYHEM

- 4 : BLOODY FRIDAY AND OPERATION MOTORMAN

- 5 : IN COMMAND

- 6 : WAR AS A WAY OF LIFE

- 7 : BACK TO BUSINESS

- 8 : OPERATING AGAINST THE ODDS

- 9 : THE WHEEL OF FORTUNE

- Plates

- About the Author

- Copyright

- Other Books