![]()

Audience Questions

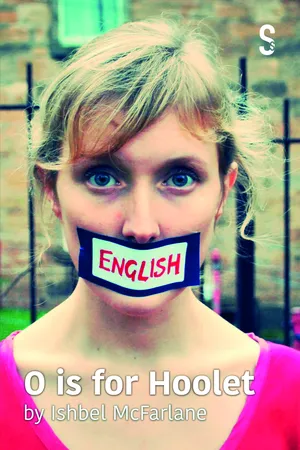

On my blog oisforhoolet.com I answered some of the questions that audience members submitted but which there wasn’t time to answer in the show.

I reproduce a selection of those questions and answers here so you can get an idea of the sorts of questions that people had, and the sorts of answers I gave in the room. I have included the date when the question was submitted – many of my answers would be different now. The posts are printed as they appeared on the website, apart from removing the hyperlinks to GIFs of Lady Kluck from the Disney Robin Hood. GIFs of Lady Kluck are what the internet is for – go there if you need them.

WEDNESDAY 15TH APRIL 2015:

What does “hingmy” mean? I hear it all the time in Glasgow

‘Hingmy’ (aka hingmie) means ‘thing’, and is often used when you can’t find the right word, or you don’t know the correct word. It’s a combination of a variation on ‘thing’ and the suffix ‘-y’ or ‘-ie’ which is often used as a diminutive or to show familiarity. You often see it in names – eg. Anne to Annie, or Tom to Tommy. FUN FACT! That practice began first in Scotland as early as 1400, and spread south. SIDE FACT: at school my name, Ishbel, was always made into a pet name as ‘Ishy’, but when I went to university with predominantly English pals, they shortened my name to ‘Ish’. I still have divided views on the nickname ‘Ish’ because I associate it with moving away from what I was used to, what I thought I’d chosen by studying in Scotland (I was certainly the token Scot in my University of Edinburgh theatre-making crowd at Bedlam). It’s also associated with some of my best pals, though, so it’s definitely mixed.

Back to hingmie. Here’s an example sentence: ‘Ma computer’s been on the blink since A plugged in the USB hingmie’. Or: ‘Turn that guff off, gie me the TV changer hingmie’. Variants include ‘thingmy’ and ‘thingy’. That use of a ‘h’ sound where there would often be a ‘th’ sound in other dialects, and in other words in the speaker’s dialect, applies elsewhere too eg. somehing = something. I have zero evidence for this, but it also feels like ‘nuhin’ is gaining ground while the older form, ‘naethin’ is losing it.

The word ‘hingmie’ is shockingly absent from the Concise Scots Dictionary, but ‘thingy’ makes it to the OED (TOP TIP: pretty much any library card can get you into the OED online where you have free access to pure hunners o information – dae it!). The OED identifies ‘thingy’ as a chiefly Scottish word, which I had no idea about until RIGHT NOW. Added to the information about that ‘-y’/-‘ie’ suffix starting in Scotland, it’s not so surprising.

This is a fair fascinatin wee hingmie, daein this here blog.

THURSDAY 16TH APRIL 2015:

Have you encountered people who say Scots is “slang?” How would you answer it?

First question answer: yup.

Second question answer: in the words of Johann Wolfgang Unger I, ‘mitigate, hesitate and negatively predicate Scots even while saying how important it is to [me]’.

When I was rehearsing Hoolet, I took my watch in to the shoe/watch repair place near my flat. The guy in there asked me whether I was off work that day. This a perennial question for freelancers who can do things like go to the bank in office hours. I sometimes just say that it’s my day off rather than explaining my complex work situation. But sometimes I get defensive about not being busy enough, because my self-esteem is pinned on whether someone I see every five months or so to pay in a cheque from my granny thinks I have a valid job. Oi.

Anyway, I explained to the guy in the shop that I was rehearsing a show. Here’s how it went from there:

MAN: Oh yeah? What’s the show aboot?

ISHBEL: It’s about Scots language? [the rising inflection of question is important here]

MAN: Oh right, like Gaelic.

ISHBEL: N-no. Like, like if you use the word hoose instead of house, you could call that Scots.

MAN: Right, like a sortae slang.

ISHBEL: Well, you could call it a slang, but it has a long history [mumbles] and so I would call it a language.

MAN: [He’s got it now] Yeah, sortae old-timey language.

ISHBEL: Well, people still speak it now. I suppose that’s what the show’s… [trails off]

MAN: That’s me done. I tightened up that second hand, it was a bit shoogly. That’s £4.80.

ISHBEL: Thanks so much. That’s great. Can I pay by card?

MAN: Aye. [Gets out chip and pin machine] Ye know, A get charged aboot 15p for usin this, an 40p or somehin fir usin it under a fiver.

ISHBEL: Oh, right, I’m [she means ‘awkward’, but can’t say it] – do you want to add that? [This last section is too quiet to really hear]

MAN: Nae worries. Yer nearly at a fiver. Ither fowk though…

[The conversation continues until Ishbel awkwardly leaves, smiling and apologising with her whole body]

To me, that man is a Scots speaker. Does he see his language as a slang? Does he see himself as just speaking English? What difference would it make to his life just now if I was to have taken the time to try and explain to him the history and validity of his idiolect? Would that have been more or less annoying than me paying by card?

BOY, DO I NOT KNOW.

THURSDAY 16TH APRIL 2015:

When will I be able to write a job application in Scots?

Pretty sure by the end of the run (25th April 2015) the whole Scots language issue should be over, so sometime early in May you should be able to apply to Morgan Stanley in Scots no bother.

Ha.

Yeah. This is a tough one. Triple threat:

1. written

2. job

3. application

Let’s go through them one by one.

ONE: WRITTEN – We’re still not used to seeing Scots written. Indeed, it bothers us that there is little standardisation in the spelling when we do see it. At times like in job applications, we tend to take good spelling, punctuation and grammar, and a formal style, as a mark of the suitability of that person for the job. We even take it as a mark of good character, even if the job will involve none of those skills. When it is hard to decide whether someone has done all of the writing ‘right’ because ‘right’ is unclear, we get all CAN’T PUT IN BOX HATE IT that humans do about so many different things.

TWO: JOB – We still think of spoken Standard English as the language of the workplace. And maybe it is. Or maybe it is in a general sense. It’s not ‘correct’ Standard English to say ‘me and Jesse are going to the shops’, but it is PERFECTLY ACCEPTABLE in spoken language, since it is clear what you mean. If someone speaks like they would write in a formal situation, we would find them pretty odd.

There is an argument that it is alright to have different linguistic registers for different areas of our lives. Maybe in a lawyers’ office with people from all over Britain, Europe and the world it makes sense to use English as a lingua franca. Lingua francas are useful, they’ve been used for as long as we’ve had language and people to talk to who aren’t our family. There are arguments that English itself began as a sort of pidgin language or creole when Anglo-Saxon, French and Norse were jumbled together in the 11th century. Such creoles can be used as a lingua franca, and in this case (if you accept this theory, which MILLIONS WOULDN’T) came to dominate and take over the other languages it was bridging, namely French, Norse and Anglo-Saxon.

For me, the problem is when you say the language we use in the office is superior to the language we use at home. The hierarchy, rather than differentiation, is the issue. I don’t know if we can sort that, though. If there’s something that humans like it’s putting things in order of bestness. So tactical use of the Scots language use in formal settings is a noble act which I applaud. However, it takes nerves of steel, especially if it’s an application…

THREE: APPLICATION – The ‘application’ aspect of this suggestion makes everything more difficult. When we send an application for a job, or similar, the reader of that application only has that to go on. In a way, our instinct in a setting like a written application is for the form of the language to disappear, and for only the content to shine through. It’s like how the mark of a good theatre technician is that no-one even noticed that they had done any job at all. Crushing. Standard English is so normative that it is seen as ‘neutral’. When we are introducing ourselves as a good option for company money, we don’t want to appear stupid, but also not flashy.

To send a job application in Scots, with no personality, reasoning, and apologetic shoulders to balance it, is an act of supreme bravery. And one that I have attempted ONCE in my life, and that was the award application for this show (so doesn’t quite count). I offered an English translation ‘on request’, but then sat in my room worrying that they wouldn’t bother with the extra effort of reading an application in Scots and would take it as an easy way to slim down the pile. I thought about how if they did that I wouldn’t want their money anyway. Then I thought about how I really wanted their money. Why was I making my life difficult when...