![]()

Chapter 1

A Theory of Postcolonial State Expansions

In contrast to the politics of uniqueness, typological theory aims at transcending the idiosyncratic. Abstract ideal types replace all claims to exceptionalism, and instead of historiographic exegesis, typological theory constructs a generalized pathway, a reconstruction of “both actual and potential conjunctions of variables, or sequences of events and linkages between causes and effects that may recur.” In order to explore the commonalities and differences that link the “Syrianization” of Lebanon, the “Moroccanization” of Western Sahara, and the “Judaization” of the occupied territories, this chapter develops a theory of postcolonial state expansions that builds on power-distributional approaches in historical institutionalism. The theoretical framework consists of three elements: a causal pathway of postcolonial state expansions, a typology of different varieties of state expansion (as well as state contraction), and a taxonomy of rule and resistance. The three elements are linked as follows: the causal pathway theorizes why some postcolonial states in the Middle East engaged in expansionist policies as a coping strategy to overcome entrenched crises of legitimacy and sovereignty, the typology explains why these irredentist projects resulted in very different outcomes, and the taxonomy theorizes expansionism as an interaction between rule and resistance. In combination, the theoretical framework responds to an overarching research question: why and how did postcolonial states in the modern Middle East expand and contract?

A Causal Pathway of Postcolonial State Expansions

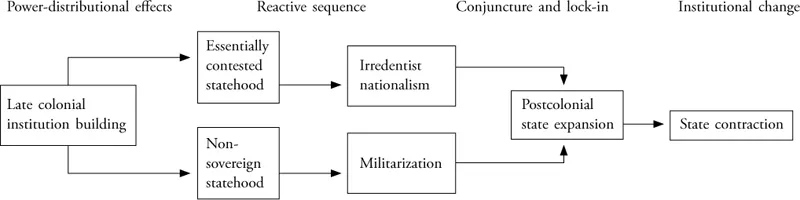

Postcolonial state expansions can be theorized as a causal pathway consisting of four different stages: colonial rule, postcolonial state formation, state expansion, and state contraction (see table 1.1). The causal pathway operates as follows. First, the model captures two distinct power-distributional effects of late colonial institution-building. After decolonization, the newly independent states were perceived as profoundly illegitimate (essentially contested statehood) without being organized into an effective state apparatus (nonsovereign statehood). Second, in order to counteract these profound legitimacy and sovereignty gaps of newly established states, state-building elites deployed militarization and irredentist nationalism as reactive sequences. Third, state expansions resulted from a conjuncture of means, motive, and opportunity: political elites did not necessarily aim at territorial enlargement per se, but they strategically grasped the chance to engage in expansionist policies when a regional conflict environment presented them with a convenient window of opportunity. The model understands the resulting state expansions as a form of quasi-permanent institutional lock-in: once expanding states had settled on a specific regime for newly captured territories, the respective type of state expansion became relatively entrenched. Fourth, the model assumes the possibility of slow-moving institutional change (including state contraction), depending on the level of organized political resistance and shifts in domestic coalition building.

Table 1.1. A Causal Model of State Expansion and State Contraction

This four-stage causal model of postcolonial state expansion can be clarified in greater detail. The power-distributional effects of colonial institution building can be traced back to the late colonial “self-destruct state.” Unlike earlier forms of European colonialism, the late colonial state (i.e., colonialism after World War I) was shaped profoundly by the Wilsonian moment, the promise of national self-determination as an emerging norm. Late colonial institution building was consequently “schizophrenic: partially determined by the legal and moral conception of Mandate and partially by self-interest.” Unwilling to rule by consent and unable to rule by force, institution building in the late colonial state consisted in rule by bricolage, a pattern of constant improvisation, and widespread arbitrariness. This rule by bricolage had two power-distributional effects: a deeply disputed nation building (essentially contested statehood) and a highly fragmented state building (nonsovereign statehood). Instead of concentrating power in a legitimate and robust state apparatus, late colonial rule resulted in a systematic dispersal of power. When the colonial powers abandoned the Middle East, what they left behind was “a state without being a nation-state, a political entity without being a political community.” The causal pathway defines these fundamental disputes over the basic Westphalian features of a nation-state (identity of the state nation, geographic delimitation of the state territory, organizational features of the state apparatus) and the overall legitimacy of state existence as essentially contested statehood.

This fundamental dispute whether a state should even exist in the first place resulted from the ever-changing territorial divisions, fragile political institutions, and systematic favoritism vis-à-vis ethnic and ethnosectarian minorities under late colonial rule. Sometimes these policies followed a strategy of “rule and conquer” (like the French “Berber policy” in Morocco), and sometimes they resulted from a mixture of competing imperial interests, racial resentment, and mere incompetence (like the British policy vis-à-vis the Zionist project). In the absence of stable and legitimate political institutions, late colonial rule raised an entire generation of broad expectations that did not struggle over public policy or constitutional amendments, but over grandiose plans to launch completely new state projects or (to put it in Gramscian terminology) “a new type of State” from scratch. The political parties carrying these miniature state projects differed on almost everything, including the state’s geographic delimitation, its organizational features, and the identity of the state nation. They could only agree on two things: the illegitimacy of colonial rule—and the illegitimacy of one another.

In addition to being essentially contested, the newly independent states were also non-sovereign: colonial administrators were not only wary of creating stable and legitimate institutions, they were even more suspicious of training administrative, police, and judicial personnel or of establishing a national army. Instead, they relied on the systematic recruitment of ethnic and ethnosectarian minorities into auxiliary forces that were fighting alongside the colonial military. However, once the colonial powers withdrew their military, they left behind a polity without a state—or at least, again in Gramscian terminology, a polity without a “State in the narrow sense of the governmental-coercive apparatus.”

In order to overcome the historical legacies of essentially contested and nonsovereign statehood, competing political elites in the newly independent states engaged in two reactive sequences—irredentist nation building and militarized state building. Paradoxically, neither of the two policies were necessarily aimed at war making or territorial expansion. Irredentist ideologies sought to anchor fragile and insecure nations in a grandiose past while promising them an even more glorious future, whether Antun Sa’adeh’s “Greater Syria,” Allal al-Fassi’s “Greater Morocco,” or Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s “Greater Israel.” At the same time, militarization aimed at jump-starting the establishment of a governmental-coercive state apparatus, a pattern of militarized state formation described by Perthes “as an end in itself and not as a prelude to actual war making.” In short, while irredentism aimed at building the nation, militarization aimed at building the state.

In most cases, militarization and irredentism did not result in any direct challenges to the regional state system of the Middle East. Often the dream of recovering lost territories simply withered away on the political fringes: the vision of “Greater Egypt” or a “Unified Nile Valley,” thus the unification of Egypt and Sudan, rapidly fell apart when Sudan opted for self-determination instead. None of the plans for a union between Iraq and Syria ever came to fruition: these failed initiatives included Nuri al-Sa’id’s Fertile Crescent plan and Emir Abdullah’s Greater Syria plan. However, in a number of significant cases—Syria, Morocco, and Israel (Iraq and Turkey might also be added to this list; see chapter 7)—both reactive sequences became interlinked in a rapid succession of military conflict, territorial expansion, and entrenched ethnoterritorial conflict. This quasi-accidental conjuncture of events can be described as the unintended consequence of a regional state system of equally militarized and equally irredentist states and nationalist movements. Without a functional pattern of regional integration, Middle Eastern states did not trust one another and rarely recognized their neighbor’s borders. The region had become plagued by both the security dilemma and the Macedonian syndrome.

As unplanned conjunctures of dysfunctional decolonization and a regional conflict environment, the initial campaigns of military conquest were surprisingly swift: Israel needed less than a week to capture the Golan Heights, the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip, East Jerusalem, and the entire West Bank. Once the reactive sequences of irredentism and militarization had become interlinked, however, they created a lock-in effect that rapidly became quasi-permanent: It took Israel only six days to conquer the West Bank, but core elements of its rule over the occupied territories would remain unchanged for the next fifty years. Despite several regional wars, intense campaigns of guerilla warfare, an unprecedented wave of international terrorism, costly efforts toward conflict resolution and decades of Palestinian state building, at least at the time of this writing, the Israeli military remains firmly in control of the occupied territories for the foreseeable future.

This institutional lock-in was, of course, no coincidence. The initial campaigns of conquest by Syria, Morocco, and Israel might have occurred almost by accident, in another proverbial “fit of absence of mind.” However, the strategic institutionalization of territorial expansion in the following years was no “accidental empire” but rather reflected the deliberate outcome of a series of strategic decisions. While the Syrianization of Lebanon, the Moroccanization of Western Sahara and the Judaization of the occupied territories followed different varieties of expansionism, the underlying logic was the exact same strategy of predatory state consolidation: the political elites of expanding states systematically deployed their grasp over newly acquired territories and their populations in order to overcome fundamental disputes o...