![]()

Part I

Screwball Love

![]()

1

Love’s Final Irony

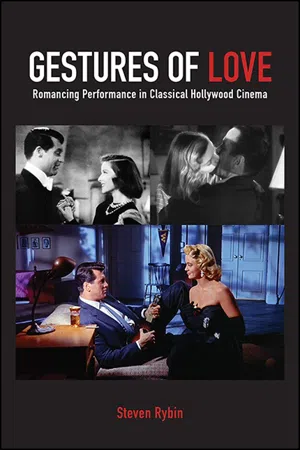

John Barrymore and Carole Lombard in Twentieth Century

But there is one side of acting that has always stirred me … This is the superiority of the actor over reality … Of the few actors that I have known who had the genius, I admired most Jack Barrymore … he was the greatest actor of my time.

—Ben Hecht (A Child of the Century 431)

ASPIRING ACTRESS MILDRED PLOTKA—Carole Lombard—is crying. Theatrical impresario Oscar Jaffe—John Barrymore—has broken her down. Poor Mildred is to play Mary Jo Calhoun in Jaffe’s latest production, Hearts of Kentucky. In this play, she is to assume the stage moniker “Lily Garland,” the dreamt-up name of the star Jaffe would like Miss Plotka to become. But she can’t get the cry right. Blocking and directing her movements on the stage with zig-zagging chalk, Jaffe has made sure Mildred knows where to stand. But she doesn’t yet know how to project her voice and body theatrically. When her character’s character is to react to her father’s death, Lombard raises her hands to her throat and gazes up at the heavens with a subtlety only a film camera could register. And Howard Hawks’s camera does register Lombard’s perfectly expressed manifestation of what is, in the context of Jaffe’s theater, Mildred’s performative failure. But, of course, in the world of Twentieth Century (1934), Mildred is not rehearsing for a movie. Mildred must project loudly enough to be heard in the back row. So Barrymore expresses Jaffe’s exasperation with her by providing a model of the performance Mildred herself cannot at this point achieve. As Lombard raises her hands to her throat, Barrymore stretches his outward, in exaggerated counterpoint to her bound gesture and in the direction of the not-yet-present audience toward which Lombard’s character will need to project on opening night. Slamming his script to the floor—in frustration, yes, but also to create an example of the kind of aural effect, heard throughout the theater, Mildred cannot yet successfully produce—Jaffe finally drives her to tears, tears more genuine than anything so far expressed in the rehearsal. And with this, Jaffe discovers, Mildred might yet become an actress. The discovery here, however, is not the tears themselves; Jaffe is uninterested in naturalism. What he wants is to bring those tears to surface, and to amplify surface loudly and beautifully enough so as to reach every row of his audience. He does not mine Mildred for tears because he wants reality; Jaffe wants to raise Mildred’s tears above reality. When she successfully transcends the prosaic, Jaffe will know he has found his actress. And she is close to that transcendence here—Jaffe knows now he has something to work with. So he offers a touching appreciation: Barrymore cradles Lombard’s tear-stained face in his hands, guides his finger along Lombard’s left cheek, the cheek bearing an ever so slightly perceptible scar, and lightly pinches it (figure 1.2).

Figure 1.1. John Barrymore, Carole Lombard, and performance pedagogy: Twentieth Century (Columbia, 1934).

Figure 1.2. John Barrymore, Carole Lombard, and the raising of tears above reality: Twentieth Century (Columbia, 1934).

This little, intimate gesture is touching, and in its own quiet way, is also above the ostensible “reality” of the scene. For all of Barrymore’s broad gesticulating and dramatic shouting in the preceding moments—for all of Jaffe’s demands that Mildred project herself to the back row—this little caress of the scar on Lombard’s cheek could only be detectable to a closely positioned camera. This gesture reminds us that while Jaffe and Lily are creatures of theater, Barrymore and Lombard are finally creatures of cinema, who touch us and make us laugh because the camera, piercing through their characters’ theatrical pretensions (without invalidating them), guides us to the authentic, human hearts beating through their self-conscious commitment to a performative life. Because tricks of photography and positioning often make the scar on Lombard’s left cheek less than salient in her movies, it only becomes a part of her character when our attention is directed there (and when we are prepared to notice it). In this shot, Barrymore draws our eye there, guiding his fingers across Lombard’s cheek with a quiet tenderness. Yet the scar serves no role in Twentieth Century’s narrative; unlike most facial expressions, which work to convey psychological content, Carole Lombard’s scar does not serve as a sign of character interiority. (Is it even really Mildred’s scar? If so, how did she get it? The film doesn’t tell us. Perhaps actors can possess features that their characters do not.) That Barrymore’s gestures should direct us, cinematically, to the surface of Lombard’s skin, then, rather than the inner life of the character she is playing, is key to the meaning of Twentieth Century as experienced.

William Rothman writes, in his characteristically brilliant book Must We Kill the Thing We Love?, that something troubles him about this frequently missing interiority in Lombard’s screwball performances. He asserts that Lombard’s characters lack the rational, inner life of, for example, Katharine Hepburn’s Susan Vance in Bringing Up Baby. For Rothman, Bringing Up Baby’s “close-ups of Susan (that is, of Hepburn) reveal that she is not really, or simply, the screwball she appears to be. Playing a screwball is internal to Susan’s perfectly rational plan to keep David close by her side until he realizes he has fallen in love with her” (67). Of Lombard’s screwball roles, only in Twentieth Century does Rothman find a brief moment of inner rationality guiding her “screwiness,” pointing to a moment late in the film in which Lombard’s Lily responds to Barrymore’s gesticulating with a thoughtful, self-aware close-up. If, for Rothman, close-ups in screwball are opportunities for the performer, elsewhere entertaining us in long-shot with irrational behavior, to convey a thoughtful inner life, he argues that in Lombard’s other screwball classics, Gregory La Cava’s My Man Godfrey (1936) and William A. Wellman’s Nothing Sacred (1937), there is no sign of this guiding intelligence. “When Carole Lombard plays screwballs,” Rothman writes, “these characters really are ‘screwy’ ” (67).

In Rothman’s sensitively philosophical hands, he uses this notion to give us revelatory readings of other films and screen heroines. But Lombard’s special kind of “screwiness” is finally readable as psychological failure only if rationality and thoughtfulness are all we expect to find in close-up, and if giddy, goofy pleasure is severed from the interior meaning it might potentially project. Lombard’s rationality, in other words, takes on a delightfully screwy form, one perhaps easy to mistake as entirely unhinged. An early scene with William Powell in My Man Godfrey suggests this idea. Lombard’s Irene Bullock encounters Powell’s Godfrey at a city dump. He is a “forgotten man”—one of the Great Depression’s unemployed. Irene is at the dump to claim him as a prize—as part of her high society’s absurd “scavenger hunt,” she is to find a homeless man to win the trophy. This scene contrasts Lombard’s character with her sister, Cornelia (Gail Patrick). Cornelia speaks to Powell’s Godfrey in a condescending inflection of voice, treating him as an object when she offers him five dollars to return to the hotel lobby as proof she has found the “forgotten man” necessary to win the scavenger hunt. Lombard’s Irene is there, at least initially, for the same purpose as her sister. Details of performance and costume, however, align our sympathies with Irene. For one, while Cornelia is wearing a dull black dress that absorbs the surrounding light rather than reflecting it, Lombard’s shimmering silver gown (like her scar, another of the details that draw our attention to the surface of her performing body) both accepts and reflects light, and is reflective of her more generous and humane attitude toward Godfrey (even as it continues to align her with the largesse of a more privileged social class). Powell’s movements toward Lombard parallel his earlier approach toward Gail Patrick, as he corners her to the edge of the frame just as he had cornered Cornelia into an ash pile. Here, the contrast between Powell’s face (cloaked in low-key shadow as he confronts Irene) and Lombard’s dress, sparkling and shimmering in the moonlight as she backs up to the right side of the frame, is vivid. As the scene goes on, Powell’s Godfrey, at first impatient with her to leave, changes his mind, and tells her to sit down. When Powell asks her if she is a member of the “hunting party,” Lombard says, quickly: “I was, but I’m not now.” Before she can give any reason justifying this sudden abandonment of the scavenger hunt, Irene moves swiftly onto her next observation, at her amusement of Godfrey’s cornering of Cornelia into the ash pile: “I couldn’t help but laugh. I’ve wanted to do that since I was six years old.” Recollecting the moment which has just passed, she bursts out laughing; but what makes the moment funny is not Irene’s recollection itself (Godfrey’s pushing of Cornelia into the ash pile was actually not that funny, to us), but the physical manifestation Irene’s giddiness, as incarnated by Lombard, takes: the staccato, high-pitched laugh; the convulsions of her head as she snickers, accompanied by the playful bob of her curly bangs, which float above her forehead (figure 1.3); and the covering of her face with her gloved right hand, as if to suggest that any facial expressions which Lombard/Irene might be revealing here (and which are temporarily masked by the hand) are less important than the sheer physical convulsion of a woman delighting in her own capacity to regard events in her world with good humor (figure 1.4). And despite the fact that Powell’s pushing of Gail Patrick into the ash pile is not particularly funny, Lombard’s delightful physical orchestration of her character’s own giddiness is. The performance guides us to the realization that what is delightful here is not what Lombard is laughing at but how Lombard is incarnating laughter, how her physical orchestration of laughter makes her viewer giddy in turn.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4. Carole Lombard floats and bobs with William Powell in My Man Godfrey (Universal, 1936).

Powell’s steady gaze and disapproving frown convey his character’s impatience with all this. Powell’s performance, in fact, confirms the use of the close-up as traditional revelation of psychological rationality and thoughtfulness, and stands in contrast to Lombard’s. Where Powell’s Godfrey wants to slow down and have, as he puts it, “an intelligent conversation,” Lombard giddily jumps into the next moment, the next observation, the next source of laughter and joy. Lombard’s character does not lack for inner life or thoughtfulness. Rather, she almost has too much inside her to express; she jumps breathlessly from one observation to the next, and through the art of this performance Lombard’s own ability to translate a bubbly, vibrant interiority immediately into external behavior, onto the surface of her skin, is conveyed with brilliance.

For those who would need proof of rather more traditional thought in Irene, however, that is present in the scene, too. At the very beginning of the scene, having witnessed Cornelia’s abhorrent behavior toward this homeless man, she has already made the decision to abandon the scavenger hunt. Later, she will confirm in dialogue that she is no longer willing to engage in such unethical behavior:

IRENE: I’ve decided I don’t want to play any more games with human beings as objects. It’s kind of sordid when you think of it, when you think it over.

GODFREY: Yeah, well, I don’t know, I haven’t thought it over.

Here Irene realizes Cornelia’s treatment of Godfrey is unethical. Throughout the film, as if to demonstrate the content of this revelation, Lombard will work to convey her character’s authentic love for Godfrey. But this burning inner desire and thoughtfulness is, in the context of My Man Godfrey, less important than the way Lombard takes her character’s inner revelation and translates it into the medium of screwball—a medium she helped invent. For Lombard’s characters, inner life matters, but what matters more is the way interiority manifests itself into external behavior, as if performance itself were a lesson in how to chiefly inhabit a way of life physically, not in place of thinking but in light of one’s thoughts.

What Lombard creates, then—and what she works to achieve alongside John Barrymore in Twentieth Century—is a demonstration that there is no necessary division between performer and form: where in most conventional films the close-up serves to enable the performer’s conveyance of inner life, in screwball—and in Lombard’s screwball films especially—the swiftly moving expressive surface of the actor (her gestures, her movements, her expressions) returns us repeatedly to the mise-en-scène around her, as if the very surface of her body were an inimitably creative intervention into the world as such, rather than merely an illustration of a scripted psychology. Lombard’s characters have ideas, but rather than taking ownership of them (say, through a close-up, in which the furrowing of eyebrows or the lowering of lips might convey an emotional state and thus a clear possession of an emotion or idea by the character), she throws them immediately out into the social world, through the medium of her body, to see if they stick or to witness what delightful and productive trouble they might cause. Joe McElhaney has noted that, in Classical Hollywood cinema, actors were often the “driving force” of films (“Howard Hawks: American Gesture” 32), and this is certainly true of Lombard in her screwiest moments. As one Lombard biographer writes, “If a movie is an orchestration of component parts, then Carole Lombard is the glamorous conductor of the screwball concerto … She defined the screwball comedy’s style and progression, and its character mirrored her own” (Swindell 304). In reading her performances for character, however, we fall into a potential trap; rather than guiding us inward toward the psychological traits it is in her (or her character’s) unique possession to grasp, Lombard throws us giddily back onto the surface of her films, and of herself, insisting that her goofy and charmingly screwy gestures, movements, and expressions be experienced as part of the film’s dynamic force, and of its force on us.

This idea returns us to Lombard’s scar, and Barrymore’s gentle caressing pinch of it: Barrymore’s gesture guides us to the “surprise enchantment” of the scar itself, and the star herself, who, when we open ourselves to her giddy movements across the surface of the screen, directs us to what it means to fully live like a screwball in light of one’s thoughts. This is not meant to devalue the thoughtful role dialogue and interiority elsewhere play in the genre, and the role thoughtfulness in screwball has played in Rothman’s (and Stanley Cavell’s) peerless interpretations of screwball form as philosophically significant. It is meant simply to remind us of the equally important point that those thoughts won’t matter much unless we first know how to inhabit them, that is, unless we know how to live like a screwball. Just as Barrymore/Jaffe teaches Lombard/Lily/Mildred how to position herself for the stage, Lombard tutors us not so much about what her films mean as how they feel, how the screwiest emotions first take shape and form on the surface of things before we can quite work through what they might mean for our inner lives or our social bearings.

There were few men in screwball comedy who could quite match Lombard in marrying the giddy surface of her gesturing and vibrations to the screwy surfaces of the films themselves. In My Man Godfrey William Powell’s character is never quite as delectably goofy as Lombard (and this is an odd aspect of Powell’s characterization in the film; his characters in The Thin Man films and Libeled Lady [1936], as the next chapter shows, can be thoroughly and giddily goofy). Nothing Sacred is another Lombard delight, too, but like Powell in Godfrey, Fredric March’s character in that film is not intended to inspire the same delights of viewing that Lombard does herself.

Indeed, the only time in Lombard’s career she would find a male match for her own delightfully comic performative style was with John Barrymore in Twentieth Century. This is because, unlike Powell in Godfrey, Barrymore responds to her movements with his own glorious, theatrical physicality, a physicality that renders immediately the thoughts and emotions of his character into joyous, bodily transcendence of whatever those around him, at any given moment, are prosaic and dull enough to understand or organize as “reality.” And his caress of the scar, in the aforementioned moment, is his tacit approval of Lombard as a worthy onscreen match. The scar bears the mark of the sheer contingency of their coming-together in this film, the lucky chance by which this filmed moment in Twentieth Century even came to exist; for the scar on Lombard’s left cheek reminds us of biographical events that might have precluded her from ever discovering, opposite Barrymore or anyone else, what giddiness her body discovers on the screen. Lombard suffered the injury leading to this scar ...