![]()

PART ONE

Mountains as “daunting terrible”: Before 1830

MOUNTAIN climbing in the northeastern United States, pursued for pleasure, is relatively young. Prior to the 1830s, few people tried to reach the summits of the region’s highest hills. Those who did were there primarily for business reasons; they were adventurers after rumored precious stones; military men seeking a lookout; land surveyors obliged to run town or property lines across high terrain; or hunters or lumbermen whose work led them up ridges. Not until after the American Revolution (1776–83) is there record of anyone climbing a significant peak for anything like recreational reasons. For the first fifty years of the nation’s existence, these instances remain rare.

The nearly complete absence of a mountain recreation impulse was not unique to Americans of that era. Although some cultures have appreciated and even revered mountain scenery for many centuries, most did not.a Europeans avoided mountains or regarded them with fear and superstition until modern times. Appreciation of mountain landscape, as well as purely recreational climbing, whether of the Alps or of lesser hills like those of England’s Lake District, were rarely heard of until the eighteenth century. The first ascent of Mont Blanc, often cited as the starting point of modern mountaineering, came in 1786, but European climbs remained isolated, almost eccentric events until the next century.

People didn’t climb because they didn’t perceive mountains in the same way we do today. Mountains were, at best, difficult and unpleasant places to get to; at worst, ugly or terrifying or the rumored abode of evil spirits or horrid creatures. One knew little about mountains, and the unfamiliar is always a little scary. “Here bee dragons,” the old maps say. Seventeenth-century geographers disputed whether the Caucasus were 115 or only 59 miles high—that’s not in the dim Dark Ages of Beowulf but in the 1600s of Galileo and Milton. A minor British poet writing in 1679 referred to the Lake District hills, later so romanticized by Wordsworth’s generation, as “Hillocks, Mole Hills, Warts, and Pibbles.”

This European attitude was the cultural heritage of the American colonists. When they first came to the New World, the earliest European explorers saw mountains in the nearby interior, but there was no campaign to go climb them. The Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazano mentions in 1524 “high mountains back inland,” which were probably the White Mountains. French explorer Samuel de Champlain saw and named the Isle de Monts Desert in 1604. Englishman John Smith drew a map in 1614 depicting Mount Agamenticus on the coast of Maine as “Snadoun Hill,” and recorded sightings of Maine’s Camden Hills and Boston’s Blue Hills. Even those ranges farther inland, out of sight of the sea, were sighted relatively early: the Adirondacks in 1535 by a French missionary near Montreal; the Green Mountains in 1609 by Champlain on a voyage down the long lake that now bears his name; the Catskills by the Dutchman Henry Hudson, also in 1609.

When the Pilgrims landed near Plymouth in 1620, and other settlements began to dot the New England coast thereafter, the mountains did not immediately assume a significant role in the settlers’ lives. Sheer survival was their preoccupation. As one historian described the first days in the New World:

At the start, all the colonizing enterprises were tentative. The little troops landed at the edge of the dark forest, the ships withdrew beyond the eastern horizon. Now was the time for survival…. The people of Charlestown, on Massachusetts Bay, in 1630 took shelter in empty casks before the first rude huts went up. In Jamestown the palisade and magazine for stores took precedence over individual convenience.

For these first settlers, clinging to life in a new harsh and hostile environment, occasional glimpses of high peaks to the north and west must have seemed uninviting in the extreme. Mountains aside, the unyielding wilderness of thick forest alone was daunting:

A waste and howling wilderness,

Where none inhabited

But hellish fiends, and brutish men

That devils worshipped.

When the earliest pioneers pushed westward to the Berkshires, they called them “horrid hills.” Even as late as 1760, soldiers approaching the Vermont hills south of Lake Memphremagog saw “even higher mountains, crammed together helter skelter, so that the land was overcrowded with them,” and their fictional narrator (in Kenneth Roberts’s Northwest Passage) can only despair: “We were coming to a terrible country: no doubt of that.”

The Native Americans who were in this region before the European settlers reportedly had little to do with the higher mountains. No trace of trails to summits, no cairns, or any other evidence of climbing the bigger peaks was found. For the Indians these mountains had no practical uses. They could not be farmed. The upper elevations were rarely frequented by game. Routes of travel naturally avoided ups and downs where possible and clearly kept away from the thick, stunted, coniferous forests of the higher reaches. In the lower, less intimidating hills—the Catskills, Hudson Highlands, Shawangunks, the miniature mountains of southern New England—Indians hunted and even made seasonal use of natural rock shelters. On these more accessible heights, Indians may even have built trails; the Indian origins of the Housatonic Range Trail seem uniquely suggested by an item in the trail description in the Connecticut Walk Book— that is, the crossing of a small stream by the name of Naromiyochknowhusunkotank-shunk Brook. But the Indians shunned the higher peaks of the northern ranges because of religious beliefs: they felt those heights were the abode of great spirits who resented intrusion. Katahdin, for example, was said to be the stronghold of a terrifying storm god, Pamola, part man and part eagle and several times larger than life. The sole report of an Indian attempt on a major peak concerns Katahdin, and that imprudent brave turned back before reaching the top.b

Under these circumstances, one could expect that no mountain climbing took place in the New World for several generations after the Pilgrims landed in 1620. In fact, both Katahdin and the Adirondacks went unexplored for well over a century, nor can any record of anyone’s visiting the higher Green Mountains be found.

This background makes Darby Field’s ascent of Mount Washington in 1642 an astonishing achievement. Just twenty-two years after the first tenuous foothold at Plymouth, the highest peak in the entire region was climbed. Field’s ascent indeed touched off a minor flurry of expeditions to Mount Washington, all in the same summer.

Then, that spasm spent, colonial America reverted to ignoring mountains, while turning full attention to taming the wilderness at hand. Relatively few ascents of any mountains were recorded during the remaining colonial years. Some of these reports concern rangers hunting for hostile Indians, such as the party led by Capt. Samuel Willard to the top of Monadnock in 1725 for its first recorded ascent. Other reports involved land speculators such as Ira Allen, who ran a town line up Mount Mansfield in 1772. A hunter named Chase Whitcher is credited with the first ascent of Moosilauke sometime during the 1770s, allegedly in pursuit of a moose. Any knowledge of the extent of such pre-Revolution climbing is, of course, limited by the scant evidence. We can never know how many adventurous individuals scrambled to mountaintops. We do know that no one who wrote of those years hints of much interest in climbing; and since those ascents of 1642 were described by early chronicles in some detail, other ascents might have received attention as well.

Besides, the northern sections of New England were sparsely populated until fewer than fifteen years before the American Revolution, so few people were physically near the mountains for most of that period. For a couple of generations prior to 1760, the northeastern United States was the scene of a struggle between English and French imperial aspirations. The French government encouraged its Indian allies to harass any English pioneers who attempted to settle northern New England. It became hazardous to be the first settler anywhere much beyond the coasts of New Hampshire and Maine. As a result, northern New Hampshire, inland Maine, and virtually all of Vermont remained without permanent settlement until the threat of French-inspired Indian raids was reduced by British victory over the French at Quebec in 1761. This is why so many northern New England towns were settled in the 1760s—and none before.

If New England’s higher mountains remained largely unexplored until after the Revolution, the Adirondacks were even less known and visited. The leading historian of that range, Alfred L. Donaldson, writes:

Stanley had found Dr. Livingstone and familiarized the world with the depths of Africa before the average New Yorker knew anything definite about the wonderful wilderness lying almost at his back door.

As late as 1756, the standard map of New York showed no details of the whole northern mountainous region, simply labeling it “Cauchsachrage an Indian Beaver Hunting Country.” “This country, by reason of mountains, swamps, and drowned lands, is impassable and uninhabited.”Cauchsachrage, a name essentially retained in one of the region’s peaks today, was variously translated “dismal wilderness” and “beaver-hunting grounds.”

Far off in the north woods of Maine, lonely Katahdin also stood remote from European settlement. In 1763 the General Court of Massachusetts (which then controlled Maine) directed a thorough investigation of the Penobscot River watershed. Capt. Joseph Chadwick, a leading surveyor of the time, was appointed to explore and describe the country and to determine the feasibility of a road from Fort Pownal (now Fort Point) to Quebec. He came back with a detailed journal, a rough map, and a negative conclusion about the Pownal-Quebec road scheme. Chadwick also turned in the first description of Katahdin, which he called Satinhungemoss Hill, in these terms:

Being a remarkable Hill for highteth & figr the Indines say that this Hill is the hightest in the Country. That thay can ascend so high as any Greens Grow & no higher. That one Indine attempted to go higher but he never returned.

The hight of Vegetation is as a Horizontal Line about halfe the perpendiciler hight of the Hill a & intersects the tops of Sundrey other mountines. The hight of this Hill was very apperent to ous as we had a Sight of it at Sundre places Easterly

Westerly at 60 or 70 Miles Distance—It is Curious to See—Elevated above a rude mass of Rocke large Mountins—So Lofty a Pyramid.

Chadwick’s map gives the first pictorial representation we have of Katahdin, along with various other peaks. But like many government reports and maps before and since, Chadwick’s papers were filed away and do not seem to have touched off any great rush to climb the mountains of Maine. It was forty years before the next recorded effort to reach lordly Katahdin. Like the Adirondacks, it remained unseen and unexplored, far off in the “dismal wilderness”—”impassable and uninhabited.”

After the Revolution, American life became more settled, and opportunities for exploration and mountain climbing opened up. Beginning with a widely reported expedition to Mount Washington in 1784, scattered instances of climbing appeared. Soon after the turn of the nineteenth century, even remote Katahdin was climbed. Sometime after 1820—later than in Europe—new perceptions of mountain landscape began to catch hold, leading to considerable interest in mountain recreation and even mountain top buildings.

But until then mountains were seen, in the words of a seventeenth-century British traveler writing about New Hampshire’s Northern Presidentials, as “daunting terrible, being full of rocky Hills, as thick as Molehills in a Meadow, and cloathed with infinite thick Woods.” No place for a sensible person, obviously.

![]()

Chapter 1

Darby Field on Mount Washington

Considering the time and circumstances, Darby Field’s ascent of what we now call Mount Washington is as noteworthy a mountaineering achievement as any other in this history.

Imagine how the first settlers perceived “the White Hills” (as the White Mountains were first known). The earliest maps of New England offer a primitive representation of the coastline and the location of settlements along it. Beyond the coast, though, are large blank areas marked as wilderness, with the general course of major rivers drawn in, sometimes by guesswork, and at their sources a vague indication of high mountains. One is reminded of the map in The Hobbit, where J. R. R. Tolkein shows the friendly settled regions of hobbits, elves, and men—and then an arrow pointing up beyond the northern wastes with the notation “Far to the North are the Grey Mountains & the Withered Heath whence came the Great Worms.” To the New Englander of the 1640s, the White Mountains must have been equally shrouded in mystery, dread, and inaccessibility. Here bee dragons indeed.

Yet, with but a toehold of colonial settlement scarcely established, Field set off on his great adventure.

Darby Field was born in Boston, England, around 1610, and came to what is now the United States apparently to escape religious persecution, probably in 1636. He moved to New Hampshire in 1638, settling first in Exeter. Early records of Exeter’s settlement include Field among those who “could not write.” By 1642 he had moved again to the area around what is now Durham, New Hampshire.

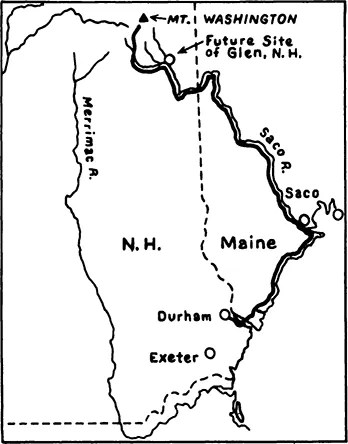

In that year, accompanied by several Indians, he set out along the coast to the mouth of the Saco and thence up the river until he reached a settlement of Indians where the river forked, in the foothills south of Mount Washington (see figure 1.1). From there he picked up local guides to take his party farther north toward the big peak. When the locals refused to go up the mountain itself, Field and his original companions made the ascent alone. The whole journey took eighteen days, probably during the month of June.

Figure 1.1. Darby Field’s itinerary, 1642 Darby Field lived in Durham, New Hampshire, in 1642. In an eighteen-day trip, he journeyed along the coast to the Maine seaport of Saco, and up the Saco River to an Indian settlement, possibly in the vicinity of today’s town of Glen, New Hampshire. From there, with directions from local Indians, he climbed Mount Washington.

Mount Washington was in a moderately ...