![]()

Part I

The Crime Lab

Gender and the Detective Genre

![]()

1

Introduction

The Case

In All about Eve (Mankiewicz, 1950), Margo Channing (Bette Davis) explains her dilemma as a woman with a career as a star of the stage:

Funny business—a woman's career. The things you drop on your way up the ladder so you can move faster; you forget you'll need them again when you get back to being a woman. It's the one career all females have in common whether we like it or not: being a woman. Sooner or later we've got to work at it, no matter how many other careers we've had or wanted. And in the last analysis, nothing's any good unless you can look up just before dinner or turn around in bed—and there he is! Without that you're not a woman. You're something with a French provincial office or a book full of clippings… but you are not a woman.

Although Margo is speaking for the woman in postwar America, she sums up the fears of all career women in Hollywood film—from the 1930s to today. According to Hollywood, a career and marriage do not mix and without the latter, “you are not a woman.” In order to succeed at a career, a woman must abandon many of her softer, “feminine” traits and embrace the more “masculine” ones of ambition, drive, and independence; however, being too masculine drives away male suitors and—as is implied in the majority of Hollywood films—life without marriage and a family cannot be considered a successful one. Thus, if a woman in a Hollywood film chooses to have a career, then she must at least demonstrate the willingness to abandon it at some point for a man. This is the product of the assumption that there is something “unnatural” (read: masculine or lesbian) about the woman who denies the socially prescribed—but perceived as natural—roles of wife and mother. The Hollywood heroine is ultimately faced with the “problem” of finding a balance between her professional ambitions and personal happiness and of how to avoid “dropping”—on her way up the career ladder—those feminine charms she will need later to catch a husband.

“Can a woman have it all—a husband, a family, and a career? The question is hardly new, but it was back then,” Mick LaSalle notes in regard to Depression-era Hollywood film (184). Films of the 1930s offered a space for the exploration of changing women's roles. Just as Ben Singer has reminded us of the existence and popularity of female heroines in the action serials of the 1910s that were since forgotten (“Female,” 91) and books on pre-Code film, like LaSalle's, that remind us that female stars dominated the box office in the 1930s, so too is one aim of Detecting Women to recover a decade of strong female protagonists and stars all but forgotten today. The proliferation of feminist film theory and gender studies has encouraged the re-examination of women's presence and contributions to classical Hollywood film, but only certain kinds of recovery work have been undertaken. Discussions of women in the 1930s and 40s tend to focus on the “bad girls” of pre-Code “fallen women” films or of film noir, or the “good girls” of the woman's film. I am interested, however, in exploring the “good girls”—women who were the center and driving force behind narratives and presented as positive models of womanhood—at the center of the traditionally male genre of the detective film.

From her first appearance in nineteenth-century fiction to the contemporary criminalist film, the female detective has struggled to be both a successful detective and a successful woman. As Kathleen Gregory Klein indicates, this was the practice from the earliest of the British detective stories and American dime novels: the female detective—whether American or British, working or upper class—was never allowed to blend effectively the two roles of woman and detective (35). The only female detectives who seem to have avoided this dilemma are those who are either too old—e.g., spinster Jane Marple and widow Jessica Fletcher—or too young—e.g., teenager Nancy Drew—for romantic relationships and thus elude the complications that arise when career and romance compete. The vast majority of fictional female detectives from 1864 to today, however, have been forced to make a decision to pursue either love or detection because the two are seen as mutually exclusive—the former requiring the detective to be feminine and the latter masculine. In terms of feminist criticism, this exclusivity has incited debate amongst scholars whether the female detective is merely an impossible fantasy as embodying both feminine and masculine traits or a realistic advancement of female empowerment. In terms of popular debate, it is often assumed that it took the Women's Movement beginning in the 1960s to spark empowered representations of women in Hollywood film and that classical Hollywood tended to construct female characters in keeping with old-fashioned (read: Victorian) values and gender roles. In the new millennium, we assume that we have made progress in terms of equal rights and opportunities across the lines of class, race, sexuality, and especially gender; however, contemporary mainstream film does not necessarily advance themes any more progressive than those touted in classical Hollywood films more than half a century ago. In fact, in Detecting Women, I will demonstrate how, before World War II, Hollywood did offer progressive and transgressive (proto-)feminist role models who resisted their socially prescribed roles. Ironically, in a decade characterized by the economic and social upheaval of the Great Depression, Hollywood presented surprisingly sophisticated and complex debates surrounding working women. My interest in Hollywood's working women is not in those women who engaged in only what were regarded as female occupations—e.g., secretary, teacher, and nurse—but those who also engaged in the assumed male profession of criminal investigation. The prolific female detective of 1930s Hollywood film was an independent woman who put her career ahead of the traditionally female pursuits of marriage and a family and who chased crime as actively as—and most often with greater success than—the official male investigators who populated the police department.

Most importantly, the female detective did so and was not punished for her transgressions of traditional female roles—as she would be in subsequent decades. Some films concluded with the female detective rejecting marriage in order to pursue her career; even though more concluded with her accepting a proposal in the final scene, the female detective was allowed—throughout the course of the story—a freedom and voice as the film's protagonist rarely offered to women in film—then and now. Indeed, the female detective was more concerned with proving her abilities as an intelligent and competent detective and “getting her man”—in terms of catching the criminal—rather than “getting a man”—in terms of matrimony. In other words, these heroines were possessed by what female detective author Mary Roberts Rinehart describes as “[a] sort of lust of investigation” (572). These women were not “something with a French provincial office or a book full of clippings;” they were strong, intelligent, exciting women who managed to balance what Margo Channing knew was impossible by 1950 and perhaps even in the new millennium—simultaneous success in their professional (“masculine”) and personal (“feminine”) lives. As such, these female detectives are exciting gender-benders that challenge the assumption that femininity and masculinity are fixed categories aligned with opposite sexes. In a decade when the Great Depression was undermining men's assumed natural place at the top of the patriarchal order through unemployment, these working women embodied an active defiance of their socially prescribed passive position and, in effect, pursued the American Dream as self-made women.

The Crime Scene Kit

For a group of films to constitute a genre they must share a common topic and a common structure (Altman, 23). The detective film has the common topic of the investigation of a crime and the common structure of the detective as protagonist driving the narrative forward to a resolution of the investigation. A genre is a body of films that have narratives, structures, settings, conventions and/or characters in common and that are readily recognizable to audiences and promotable by producers. For example, a film with a hardboiled hero sporting a fedora, trench coat, gun, and cigarette, operating in the shadows of city streets at night or in the rain, and faced with the temptation of a sultry but potentially dangerous woman is likely a film noir. A genre is the product of popularity: the box-office success of one type of film leads to imitators and, once a critical number of films sharing similar tropes and structures appears, a genre is declared. A film's popularity may, of course, be influenced by a variety of factors: a star's appeal, a director's name, an effective advertising campaign, positive word-of-mouth, or a specific release date, etc. I would assert, however, that films that offer protagonists, narratives, issues, or themes that seem outdated in terms of contemporary social attitudes will be unlikely to prove popular with audiences and inspire imitation. Correspondingly, while audiences like to see the same kind of film over and over again, they do not want to see the same film: innovation and change are as much a part of a genre film as its familiar conventions. As Rick Altman argues, change must occur within a genre otherwise it would go sterile (21). Genre hybridity (blending conventions) and parody (sending up established conventions) make genre films appear fresh to audiences.

The focus of Detecting Women is the detective film that offers a female protagonist at the center of the narrative and who actively—physically (i.e., as a crime-fighter) and/or mentally (i.e., as a sleuth)—investigates a mystery surrounding a crime or a criminal racket. Many mystery-comedy films and series focused on married detective couples—inspired by the popularity of MGM's Nick and Nora Charles (William Powell and Myrna Loy) in The Thin Man (Van Dyke, 1934). MGM made five additional “Thin Man” films (1936–47) and started a new series featuring Joel and Garda Sloane (1938–39).1 Columbia tried to compete with MGM's sparring couples with their own, William and Sally Reardon (1938).2 The couple-detective film sees the married twosome work together on a case with the male detective as the lead investigator and his wife as his assistant in a Sherlock Holmes/Dr. Watson dynamic. However, Detecting Women excludes the popular detective-couple film as it deviates from the core theme explored in films with a central female detective; namely the struggle of a single woman in pursuing a career in a male world. The female detective can be an amateur—a schoolteacher, nurse, or reporter who investigates the murders that occur in the course of her day job—or a professional of which there are far fewer until the 1990s—a policewoman or private investigator who investigates crime for a living.

I concede that for many people the term “detective” can evoke ideas of the classical sleuth rather than necessarily other kinds of investigative protagonists.3 In the broadest sense, there are two types of detective-hero (male or female): the criminologist (the popular term in the 1930s)/criminalist (the popular term today)—better known as the sleuth—and the undercover agent (professional)/crime-fighter (amateur).4 These two types are distinguished by their relationship to the community they investigate and their skill set as investigators of crime. In the case of the criminologist/criminalist, the criminal typically works alone and his or her crime is murder rather than a drugs or prostitution racket; the detective occupies a position as an outsider with specialized knowledge—whether deductive reasoning, behavioral profiling, forensics analysis, crime scene investigation, or personal familiarity—that can be utilized to investigate a crime. Rather than being on hand to witness criminal acts, the criminologist/criminalist arrives after the crime has been committed and must “read” the evidence to identify “whodunit.” This type of detective does not necessarily have to possess fighting or weaponry skills in order to defeat the criminal physically but, instead, requires a degree of intelligence and/or experience to unravel the mystery or outsmart the criminal. While the investigation of the criminologist/criminalist includes analyzing clues, questioning witnesses, and drawing conclusions from the information gathered, that of the undercover agent/crime-fighter involves being on hand to witness the criminal activities. The undercover agent/crime-fighter has specialized knowledge and/or skills that allow her to infiltrate a specific criminal community, pass effectively as one of them, and ultimately expose the ring from the inside. It is in this undercover mode that the female detective employs the masquerade of femininity to disguise her more “masculine” (i.e., crime-fighting) abilities from the criminal ring and the threat they imply. In other words, her femininity functions as a decoy—as the television series “Decoy” (1957–59) starring Beverly Garland as an undercover cop confirms. Lastly, in the case of the undercover investigator, rather than the identity of the criminal(s) being a mystery—i.e., whodunit?—the aim of the investigator and the conclusion of the investigation are to see the criminals brought to justice. While sleuthing is mainly a mental process that can be undertaken in absentia of the crime scene (thus the idea of the “armchair detective” who can solve the mystery without leaving her own living room), crime-fighting is a physical process involving both being present during the criminal activities and in terms of the method by which the criminals will be defeated.5

Whatever the ability of films to reflect social reality, it is imperative to bear in mind that Hollywood's is, using Richard Maltby's term, a “commercial aesthetic”: the primary function of a Hollywood film is to entertain in order to attract audiences and make a profit (Hollywood, 14–15). Therefore, Hollywood narratives and characters are likely to be more exciting and dramatic than the reality that generates them. The number of star “girl reporters” investigating headlining stories in Hollywood films of the 1930s was not representative of the reality of women's experiences in journalism with the vast majority of them relegated to the society column; however, Hollywood is quite accurate in its omission of female police officers and federal agents from its narratives until the 1990s as there were few in reality. Instead, the vast majority of Hollywood's female detectives are amateur sleuths or undercover crime-fighters who investigate out of personal interest rather than as a career detective. Whether or not the representation of female detectives is grounded in reality is less the issue than what those representations and their alteration over time indicate about changing social attitudes toward women and heroism.

The male detective has appeared consistently in Hollywood film since the coming of sound in the late 1920s, which made possible the cinematic rendering of the convoluted plots and dialogue-heavy explanations of the classical detective story. As I have explored previously in Detecting Men: Masculinity and the Hollywood Detective Film (2006), the British classical sleuth and the softboiled versions of American fiction's hardboiled detectives dominated the screen in the 1930s; the 1940s saw both replaced by the American hardboiled private eye in film noir; the private eye was replaced by the police detective who shifted from conservative and stable in the late 1940s, to neurotic and often corrupt during the 1950s, to almost absent from the screen in the 1960s, to a violent vigilante by the early 1970s. The hardboiled private eye returned in the late 1970s and early 80s but was overshadowed by the dominance of the cop as action-hero by the mid-80s. The 1990s and 2000s, however, saw the return of the sleuth in the educated, intelligent, middleclass criminalist. Although other kinds of detectives existed during each of these decades, these were the dominant trends within the genre of the detective film and each represents a shift in social attitudes toward law and order and the type of masculinity that society deems heroic. This is the history of the male detective, however, and I have been as remiss as other scholars for all but ignoring women in my research and writing about the detective film.

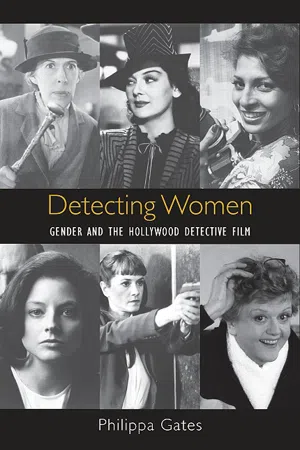

The aim of Detecting Women is to redress the exclusion of women from discussions of the genre as central heroes. As such, this study delineates the popular trends in terms of the female detective in film, the social issues that each trend explores, and the social attitudes toward women that each espouses. Surprisingly, the female detective appears alongside her male counterpart early in both detective fiction and film and, in the 1930s, tended to be an amateur sleuth, an undercover agent, or a girl reporter. The “masculinity” that defined the character in the 1930s gave way to her feminization in the early 1940s, and her pervasiveness during the Depression was succeeded by her gradual disappearance in the immediate post-World War II period. In marked contrast to her independence, fast-talk, and career success of the 1930s, the female detective—in her handful of outings in 1940s film noir—wanted to be a dutiful wife rather than an independent career woman, and her only motive to unravel the mystery was to save the man she loves. After 1950, the white female detective left the big screen, except for a couple of rare outings, until the 1980s. In the early 1970s, however, there was a cluster of black female investigators in blaxploitation films and, just as the white male detective had become a vigilante hero at the time, so too was this female detective a crime-fighting avenger. In the 1980s, the female detective exploded in popularity—on television with cops Cagney and Lacey and sleuth Jessica Fletcher; in fiction with hardboiled private eye V.I. Warshawski and FBI profiler Clarice Starling; and in film with the prolific female lawyer. The female detective continued in popularity in the 1990s and 2000s and, just as the male detective had become a criminalist, so too did the female detective become an expert in crime scene investigation, behavioral science, and forensics.

My interest in the figure of the female detective is manifold. Although there have been many studies produced in recent years exploring the role of...