![]()

SECTION 1

Agitate! Agitate! 1776–1890

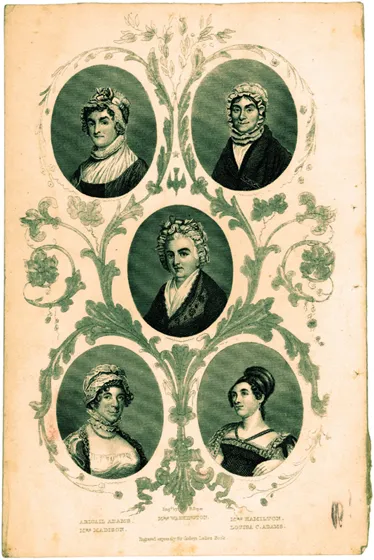

“Abigail Adams, Mrs. Washington, Mrs. Hamilton, Mrs. Madison, Louisa C. Adams,” engraving, R. Soper, in Godey’s Lady’s Book, date unknown.

This illustration, depicts the wives of some of the founding fathers, including Abigail Adams. Despite living in an era where they were generally seen as an accompaniment to their respective husbands, this group of women boasts a lengthy list of achievements. Courtesy of the New York State Museum, H-1940.17.1420.

The 1848 women’s rights convention, held in Seneca Falls, New York, is often referenced as a starting point of the women’s rights movement in the United States. Certainly, this event propelled the cause to a much more prominent place in the reform discussions of the nineteenth century. However, women and men had been talking, writing, and working for equality for a long time.

IN WRITING AND IN SPEECH

During the Revolutionary War, many American women closely followed the discussions of patriots, hoping for better rights for both women and men. Abigail Adams expressed this hope, to her husband, John Adams, as he served in the Continental Congress. Abigail made frequent entreaties that as the representatives worked to set up a new government, they should “remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors.”1 She also declared the need for greater education for women, writing to John,

If you complain of neglect of Education in sons, What shall I say with regard to daughters, who every day experience the want of it. With regard to the Education of my own children, I find myself soon out of my depth, and destitute and deficient in every part of Education. I most sincerely wish that some more liberal plan might be laid and executed for the Benefit of the rising Generation, and that our new constitution may be distinguished for Learning and Virtue. If we mean to have Heroes, Statesmen and Philosophers, we should have learned women.2

Abigail complained, “whilst you are proclaiming peace and goodwill to Men, Emancipating all Nations, you insist upon retaining an absolute power over Wives.”3

Following the war, there were new expectations for the education of men, for them to become self-reliant and productive citizens. While women were still barred from participating in government through voting, their role as the mothers who prepared future citizens was recognized. Through this concept of “republican motherhood,” women experienced some expansion of their educational opportunities, just as Adams had called for.

“Frances Wright,” engraving, ca. 1881.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage honored Frances Wright’s contributions to the women’s rights movement by featuring her portrait on the frontispiece of the first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage. They focused on Wright’s attacks on the lack of separation of church and state, the impact the relationship had on women, as well as the persecution Wright received for speaking out on these views. In History of Woman Suffrage, Vol. 1, frontispiece. Courtesy of the New York State Library, Manuscripts and Special Collections, 324.3 S79 V.1.

British author and educator Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797) published the treatise A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792. In it, she pointed to the lack of educational opportunities for middle-class women as the root of their oppression. Wollstonecraft’s essay was certainly on the minds of women reformers in America, since she was frequently cited in their writings through the mid-nineteenth century.

Born in Scotland, Frances “Fanny” Wright (1795–1852) traveled extensively in the United States in the early nineteenth century. Her observations about American life during her first visit to the states (1818–1820), especially concerning slavery and women, made their way back to Europe in her letters, and she later published her experiences in Views of Society and Manners in America.4 During her second visit, she began speaking on “theology, slavery, and the social degradation of woman,” gaining the opposition of the clergy and the moniker of “infidel.” She was the “first woman who gave lectures on political subjects in America.”5

In 1839, Margaret Fuller (1810–1850) began her first series of guided discussions in Boston, which she called “conversations.” Initially open only to women, the gatherings were intended as an intellectual outlet, since women could not attend Harvard like their male peers. Discussion often centered on women’s rights, through the lens of ancient philosophy.6 Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote later in life about attending a series during her time in Boston (likely the 1842–1843 season), and she later held her own weekly meetings “in imitation of Margaret Fuller’s Conversationals.”7

Fuller recorded some of her thoughts on women’s rights in an essay, “The Great Lawsuit,” published in The Dial in 1843. It was later reprinted as the book Woman in the Nineteenth Century in 1845. Fuller encouraged women to embrace self-fulfillment as individuals, rather than as men’s subordinates, and argued for equality for women in marriage and opportunities for women in education and employment.

Judge Elisha P. Hurlbut (1807–1889) published his Essay on Human Rights in 1845.8 Hurlbut, of Albany, was elected to the New York State Supreme Court the same year as Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s father, Daniel Cady. He argued that government existed to protect the rights of citizens, not take them away, and that all humans were entitled to a set of rights, determined by an individual’s ability to contribute to society, not by sex or race. Hurlbut’s book was cited in women’s rights circles, and as late as 1876, Stanton contacted him to obtain extra copies to give away.9

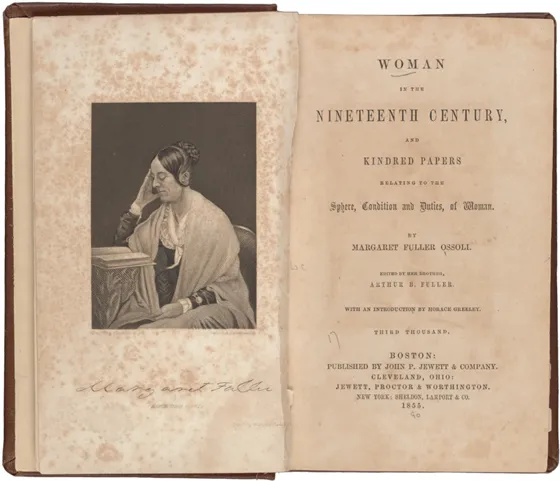

Woman in the Nineteenth Century, book, Margaret Fuller Ossoli (1810–1850), 1855.

This 1855 edition of Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published with the help of Fuller’s friends, after her untimely death in a shipwreck off Fire Island. It includes writings from Fuller’s papers, recovered after the shipwreck, which were not included in the 1845 edition. Courtesy of the General Research Division, the New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

PETITIONING THE NEW YORK STATE GOVERNMENT

Petitions to various government bodies were an important tool used by reform movements in the nineteenth century. Several petitions relating to women’s rights issues were sent to the New York State legislature prior to 1848, and they became even more frequent following the Seneca Falls Convention. The first of such petitions asking for married women’s property rights was compiled by Ernestine Rose in 1836.

In 1846, six women from Jefferson County wrote a petition that was sent to the New York State constitutional convention. Signed by Eleanor Vincent, Susan Ormsby, Lydia A. Williams, Amy Ormsby, Lydia Osborn, and Anna Bishop, the petition was presented to the convention by delegate Alpheus S. Greene. Its sentiments were in keeping with Hurlbut’s view that government existed to protect rights, not limit them. The petitioners declared that New York State had “widely departed from the true democratic principles upon which all just governments must be based by denying to the female portion of community the right of suffrage and any participation in forming the government and laws under which they live,” including imposing upon them taxation without representation. They requested that the government modify “the present Constitution of this State, so as to extend to women equal, and civil political rights with men.”10 Three other similar petitions were sent to the New York State Legislature in 1846 alone.11

Central to the discussions during the 1846 New York State constitutional convention was the idea of married women’s property rights. Modeled after English common law, New York State law stated that a woman’s property went to her husband at marriage. This was a concern to even wealthy conservatives, who could watch assets left to their daughters be squandered away by their daughters’ husbands. In fact, the law had not always worked this way in New York State: under Dutch rule, women could and did own and inherit property. A law to protect women’s property upon marriage was first proposed by Thomas Herttell in 1836, and again in 1837. The law finally passed in 1848, after twelve years of bills, petitions, and much debate, making New York the first state to secure equal property rights.12

ERNESTINE L. ROSE

Ernestine L. Rose (1810–1892) was born in the ghetto of Piotrków, Poland, the daughter of a rabbi. Following the death of her mother, a falling out with her father over a marriage he had arranged for her, and her successful defense in court of her own inheritance from the spurned suitor, Ernestine left home to ...