![]()

Part I

Alfred remembers

![]()

1

Fares Bozeid Moujaes

At the time of the emara

Alfred woke up in the early hours of the day, as was customary for him. He wore his dark gray striped suit and white shirt that bore his initials, and he sat on the porch on his caned wooden seat. He faced the garden and the Mamluk-style fountain, his back to the household through the entrance door, open as always. He sat there, as did the farm owners in his dear Louisiana on their rocking chairs on a hot day, passing the time and talking to the passersby. His wife, Najibeh, prepared coffee for him, a whole pot, which she placed in front of him with the small, cone-shaped cup that held small measures, enough for just one sip, or shaffeh as it is called. Of shaffehs he will have many, whether freshly brewed or cold, as he will sit there all day only moving to the dining table, the sufra, when called for lunch, which Najibeh dexterously prepares for her large family. Alfred never set foot in Najibeh’s kitchen, not that he couldn’t brew his own coffee, but she wouldn’t allow it. “Men should be served,” she would say and motion him off to his throne whenever he came close to suggesting he help himself. In the house, she laid down the law, to the extent that Alfred more than once suggested, “She should wear the pants.” Strong she was, yet she never deviated from the age-old social intricacies that reflected the conservative and patriarchal tendencies so prevalent in the Middle East.

When Alfred stood to shave his beard at the hat stand, the highest piece of furniture in the large sitting room, one of his daughters, Lodi usually, would hold the towel as he chipped off small flakes of soap and lathered them in a bronze cup. And this he did twice every day while humming the tunes of the Byzantine repertoire he had learned at the church next door. Out on the porch, he sipped coffee and smoked the locally manufactured bafras or tatlis, consuming no fewer than three packs of these cigarettes a day. He sat there every day and contemplated his success, a landowner now, a holder of large estates across the region. Saint Elias, the patron saint of the church next door, had looked over him well. The church had been standing for a long time, long enough to see the first of his Shwayri ancestors settle in the village in 1807.

Alfred knew little of his great grandfather, only that Fares Bozeid Moujaes had been a stonemason and had come from Shwayr and was named for his village of origin when he settled here in Hadath. The name Moujaes was dropped for the Shwayri of convenience. Alfred didn’t know that Fares represented a long line of stonemasons that traced its origins to the southern tip of the Arabian Peninsula. Stone cutting and building were crafts his ancestors had mastered, having engaged in large construction projects back in Yemen, the land of riches and abundance. The Dam of Ma’arib in Yemen, described in history books as a jewel of construction since the early sixth century BCE, was but one example of the ingeniousness of these engineers and builders. Then many tribes fled Yemen after the economy plummeted as a result of internecine wars and the meddling of mighty Rome in the trading of commodities, activities that had once made the fortunes of the original inhabitants. Of these commodities, frankincense was most important, but wealth also came from spices and other rare products of Africa and India, and even the distant Far East.

The migrating tribes trekked across the Arabian Peninsula, many settling in the Hauran area, southwest of Damascus, where they developed commercial ties with the Byzantines, then lords of the land. In this new region, the gifted builders developed their skills further and put them to use under the Byzantine emperors, who required many stonemasons and paid them lavishly, as did Justinian, who built fortress after fortress on his eastern flank, which faced the threat of the ruthless Persian Sassanid Empire. But not only fortresses did the ancestors of Fares Bozeid Moujaes build. They also lent their skills to grand realizations ordered by Emperor Justinian who built numerous churches across his empire, the cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople being unequivocally the most impressive. But empires decline and give way to newer ones, and the Byzantine Empire was no exception. When the Ottomans swept over Hauran in the early years of the sixteenth century, the Moujaes became refugees again and, after a difficult journey to Akkar in the northern mountains, took refuge in the heights of Shwayr.

Alfred knew the village of Shwayr very well. He was a regular visitor and had family and friends there. He even bought property there. Najibeh knew it equally well, as she had lived most of her life in its vicinity, the daughter of Abdallah Meshrek, a learned man who held high positions under the Ottoman governorship.

Founded on a small cliff (its name means “small cliff”), Shwayr faces inward to the east. It sits in a fabulous gorge, formed by the succession of foothills that run from Mount Sannine and drop sharply from five thousand feet to the blue Mediterranean Sea less than fifteen miles away. The sight of the Sannine from Shwayr, with its satin-white snow in spring, is awe inspiring. These are the everlasting snows that were praised in the Bible and by early travelers, but with global warming, changes in demography, and the intensive use of modern technology, the snows of Sannine have become rather seasonal. Despite that, Sannine is lovingly said by locals to “wear winter on its head, spring on its shoulders, autumn in its bosom, and to have summer sleep at its feet.” The peak is the sturdy guardian of time and the rearguard of Metn, the large region comprised of the valleys that climb eastward from the sea, cutting into the continuous chain of mountains that run along the longitudinal axis of Lebanon, with Kesrwan to the north and Shouf to the south.

At the time of their migration in the sixteenth century, the Moujaes must have looked at Shwayr as an impregnable fortress, rising three thousand feet above sea level, with a shallow gorge at its feet and facing the mighty Mount Sannine. Facing east, it had its back covered from the sea, invisible to the passing armies and those who sailed along the shores of Lebanon. In a nod to Cairo, it was called Shwayr Al-Qahira (“Cairo” in Arabic), “the Impregnable,” an acknowledgment that the town had never been invaded nor occupied by an army, a striking fact in a land that had been crisscrossed constantly by different civilizations since the dawn of time.

For the Moujaes, Shwayr was the perfect asylum. Coming from Hauran, they saw in the hospitable gorge a hideaway from the sacrilegious invaders who dared to profane Hagia Sofia. The righteous Islam of the early caliphs was done with, they thought, and recent events hinted that a new Islam was being ushered in, one that was ruthless and brutal. Shwayr offered a refuge where the Moujaes could practice their Greek Orthodox faith unafraid. They arrived in successive groups between 1517 and 1532, built a church next to a millenary oak, and settled down. (A detailed history of the Moujaes family is given in appendix 2.)

Of silk and stone

The great-grandfather of Alfred Nicola was born in Shwayr in 1788, a period of upheaval across the world. Europe was in turmoil and revolution was looming on the horizon. Royalty in France was on the brink of collapse: the Bourbons were soon to walk to the guillotine, leaving the Jacobins to plunge the country into the Reign of Terror. Had television existed in those days, the parents of Fares would have seen a triumphant Napoleon campaigning in Italy against the Austrians and the United States of America coming to life from the womb of a war for liberty and independence. They would have seen a live broadcast from Philadelphia the day the Declaration of Independence was ratified, and they might even have seen the grand drawings of Charles L’Enfant, whose plans for the new nation’s capital were just starting to be put into place when Fares turned five. Great moments in history, certainly, but who in Shwayr was to know? Life at the Moujaes household revolved around simple things, and when Fares turned five, his hands were put to use. He would spend most of his days picking mulberry leaves to feed the tiny worms that sat in container boxes and squeaked all night long in the sitting room where he also made his bed.

Silk growing and trading were common practices among village people in Mount Lebanon, the region in which Shwayr is located. The Moujaes, like many others in Shwayr, depended on this business. It was not their main occupation, as the seasonal sale of cocoons to silk spinners could not possibly feed a family, but it was a source of supplemental income they could rely upon when, come winter, Fares’s father returned from the faraway lands where he worked as a stonemason. A master stonemason, Fares’s father had built his own house in Shwayr, a simple two-room dwelling walled in stones that he cut himself along with others from the village who shared their labor to build each other’s homes. The inside walls were plastered with thick clay, which kept in the warmth in winter when five feet of snow covered the picturesque landscape. The roof was made of earth, piled on a thick mat of straw that rested on large beams and cross poles. It was thick, to keep out the rains, and was compacted with a heavy stone roller during the winter.

Winter months were probably the happiest times for Fares, who had the snow to thank for his father being at home, the only family time they had together. Life in those days was harsh, and nothing came easy. While Fares’s father was away most of summer and autumn, his mother spent her time replenishing food stocks for the winter, the mouneh, which she kept in the second room, next to the tools, firewood, and other necessities. She stored a large variety of cottage foods in this room: meats, which she diced and fried and kept in clay pots sealed with animal grease; tomato paste in jars; olives and olive oil; all sorts of marmalades; syrups made from blueberries and mulberries; dried fruits such as figs, apricots, and raisins; nuts and pine nuts; oats and wheat. She made her own flour from the wheat, grinding it with a pestle and then baking it in the mawqadeh, the fireplace that had so many functions in this same sitting room. The smoke-blackened ceiling contrasted with the chalky white-plastered walls and the floor of packed-down, iron-colored sand.

The whiteness of the walls was striking, repainted completely each summer after a season of silkworm nurturing. This season started in spring when the tiny worms were eager to start their metamorphosis, about the time when Fares’s father, like every other stonemason of Shwayr, left his family for work in “foreign lands,” or ard al-gherbeh. The life of the Bozeid Moujaes was orchestrated by the cycle of the seasons. A turning point in Shwayr came at Easter, when Orthodox Lent and its fifty-day fasting period came to an end and the Eid was proclaimed in great pomp. Families celebrated together the resurrection of Christ before the men packed their tools and headed out to a new season of construction work.

While his father was away, Fares’s mother filled the walls of her sitting room with a framework of poles made of mulberry tree branches, tying them into a grid in which the mulberry leaves were positioned. In this, the worms were placed, and they ate the leaves with an ogre-like appetite. Fares helped pick the large, thick, crunchy leaves and bring them to the framework every day, and the worms grew bigger by the hour. From tiny, squeaking bugs, the silkworms grew massive and then stopped eating to begin the pupal transformation into chrysalides. After forty days, the tiny insects yielded a forest of large silk cocoons that Fares’s mother sold by the bundle to spinners who crisscrossed the countryside on buying trips.

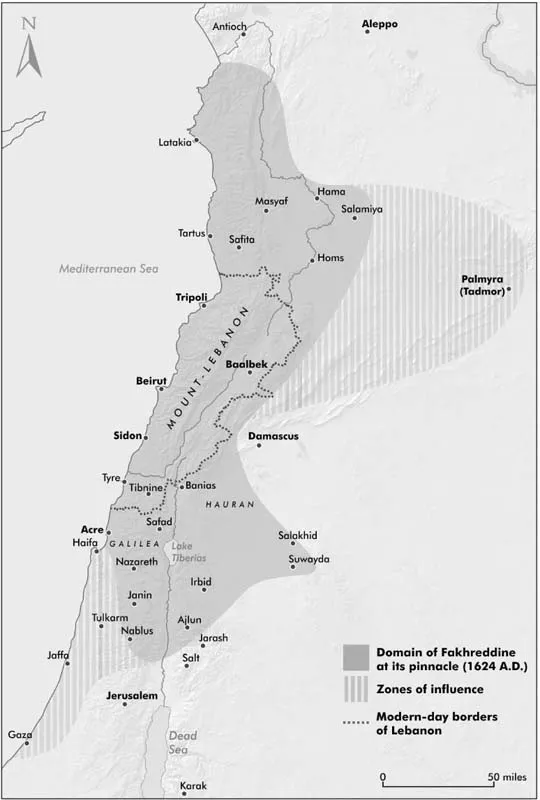

The silk industry was very prosperous then and would develop further in the coming century to become the main source of wealth in Mount Lebanon. Sericulture had existed there since the seventeenth century, thanks to the forward thinking of Amir Fakhreddine (1572–1635), the ruler of a large territory that extended in its heyday from Gaza in the south, to Latakia in the north, and deep into the Syrian hinterland as far as Palmyra in the east. He governed under the tutelage of the Ottomans, who confirmed him in his role of governor of the sanjak of Saida, a province that fell at that time under the auspices of the wali (the provincial governor) of Damascus and included all the mountains extending from Kesrwan to the Shouf. Saida, the biblical Sidon, was a harbor city that served these highlands, as did Tripoli, in the north, serve the Syrian hinterland.

Being so powerful, Fakhreddine managed to sign the tax-farming contract, the muamala, with the wali, which gave him the right to manage the territories to his benefit and, from the standpoint of the Ottomans, to enrich the imperial treasury in Istanbul from levies on the local populations. For the Ottomans, the rationale was clear: who other than a local and powerful dignitary could levy taxes across a rugged and inaccessible terrain and hold the populations in check? Fakhreddine was the obvious choice. The amir, however, had other plans, and taking advantage of the war that was raging between the Ottomans and the newly established Safavid dynasty in Persia, he turned his emara into a socioeconomic model that gave birth to a new system of governance. He collected less tax, improved the conditions of the working class, developed irrigation systems with the help of the Venetians (with whom he openly maintained relations), organized a standing army, and built fortresses across his ever-enlarging territories.

The Ottomans soon grew disenchanted with this exuberant and indomitable amir, and for a time Fakhreddine had to lay low, and so sailed for Tuscany. He remained in Florence for four years, where he learned from his friends, the Medici, the intricacies of governing a transforming society where art and architecture coexisted with modern economics and riches poured in from newly discovered continents. By extending their hospitality, the Medici befriended a potential ally who could be useful if, come the day, they mounted a new crusade to liberate the Holy Shrines of Jerusalem. Amir Fakhreddine also spent time in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in Napoli as a personal guest of the king of Spain. Exiled Fakhreddine may have been, but the four to five years he spent in the bustling lands of the Renaissance gave the amir alliances and food for thought.

Map 1. The territorial expansion of Fakhreddine the Great

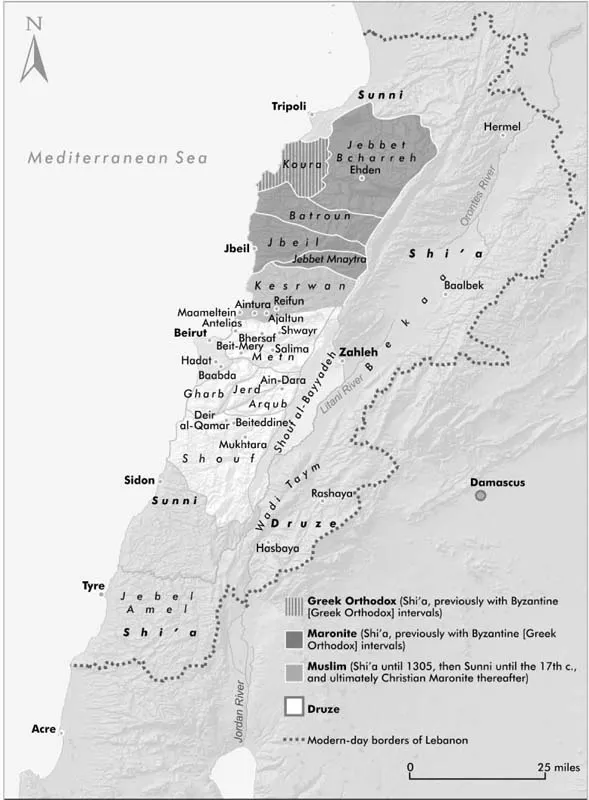

Map 2. The seven fiefdoms (emara) in the times of Amir Fakhreddine

After brokering a deal with the Ottomans to return home, in 1618, Fakhreddine spent time organizing his administration and rebuilding his village of Deir al-Qamar, turning it into the power center of his dominions. And when it came to construction, Fakhreddine knew where to get good stonemasons. If his architects and engineers were mostly Florentines, the stone workers were from Hauran and Shwayr, many of the Moujaes family, ancestors of Fares Bozeid Moujaes and Alfred Nicola.

At the time of Fakhreddine, the southern part of modern-day Mount Lebanon was inhabited by the Druze, a dissident sect that had splintered from Muslim Shi’a in the eleventh century in Fatimid Egypt and sought refuge in the hills that took their name. Until the nineteenth century, the part of Mount Lebanon extending from Kesrwan to the Shouf was called the Mountain of the Druze; at that time, “Mount Lebanon” only referred to the northern part that had come to be inhabited by Maronite Christians about the same time (see “Mount Lebanon in history,” appendix 1, for a discussion of the origins of the different communities of Lebanon). Communities lived separately and had very little interaction until Amir Fakhreddine, enlightened most probably by his years in exile, endeavored to build an agrarian economy based on crop and silk production. For this, labor was needed, and Fakhreddine saw the hard-working Christian Maronite community living in the north as a good source of workers. The Maronites had come to the region after having been persecuted by the Byzantines and were pushed into Mount Lebanon from their lands on the Orontes River, in western Syria near the northern frontier of modern-day Lebanon. In the mountains, where rains were plentiful, they mastered terrace agriculture, which made them experts at subduing the inhospitable, cold, and hilly terrain.

Manpower was not all Fakhreddine wanted, however; he also had political reasons to usher the Maronites into the lands of the Druze. The amir was himself a Druze, and although he lived and governed among his coreligionists, they did not enjoy unity. The Druze community was divided by power struggles among families, and also by tribal differences that s...