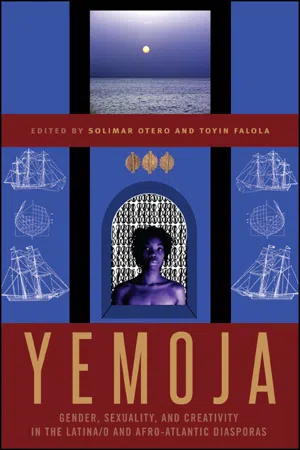

Yemoja

Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas

- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Yemoja

Gender, Sexuality, and Creativity in the Latina/o and Afro-Atlantic Diasporas

About this book

Finalist for the 2014 Albert J. Raboteau Prize for the Best Book in Africana Religions presented by the Journal of Africana Religions This is the first collection of essays to analyze intersectional religious and cultural practices surrounding the deity Yemoja. In Afro-Atlantic traditions, Yemoja is associated with motherhood, women, the arts, and the family. This book reveals how Yemoja traditions are negotiating gender, sexuality, and cultural identities in bold ways that emphasize the shifting beliefs and cultural practices of contemporary times. Contributors come from a wide range of fields—religious studies, art history, literature, and anthropology—and focus on the central concern of how different religious communities explore issues of race, gender, and sexuality through religious practice and discourse. The volume adds the voices of religious practitioners and artists to those of scholars to engage in conversations about how Latino/a and African diaspora religions respond creatively to a history of colonization.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Part 1

Yemoja, Gender, and Sexuality

Invocación

En busca de un amante desempleado

con su aire contaminado de turistas y disidentes insólitos

donde la joven oferta de un vestido ajustado

a las circunstancias de la última moda

cabalga de ironías por el malecón

entre aparentes cócteles exóticos

y la perenne indiferencia de un comisario

confuso también a la hora de persuadir.

La Habana estaba ahí,

mía y más sensual que de costumbre

asomada como siempre a sus balcones

mirando sin cansancio

hacia el mar de muchachas y muchachos en pretérito

sobre monturas de vinyl

y el reflejo de una discoteca prohibida

con aquella vertiginosa silueta oscilando la pelvis

frente a un rostro pálido improvisado y desconocido,

por supuesto, con ropas de ultramar.

no hay tiempo qué perder para el pobre mendigo

que busca la ocasión propicia para el manoseo y el juego entre lenguas.

estamos en presencia de una época atormentada por tantas dolencias.

porque mañana por la tarde ya sería esta noche

y también otra madrugada tranquila

gratificada con una cena suntuosa

o sencillamente una cena sin atuendos importados

durante el tiempo que reine la austeridad

o una simple invitación atrevida.

el dilogún solitario que presagia malos agüeros

ronda travieso por la tierra sedienta de tantas bondades desaprovechadas

incoherentes ofrendas y rogaciones mancilladas.

como aquella destinada a socorrer al desvalido

y tal parece que este lunes de hoy derrocha cierta soberbia

que nunca antes fue del todo racional.

O mío Reina del Mar!

Tú que te atreves de espumas a cabalgar sobre Taurus

entre ricas turquesas que adornan tu amable corona.

Tú que siempre desoyes el grito cómplice del iniciado

antes del crepúsculo y sigues de largo entre mis brazos

acompañada solamente por el sonido de cocos secos

que siempre permanecieron secos.

y hablabas contigo misma

procurando satisfacer la frescura de la miel

en la punta de los senos

revolcando tu cuerpo fresco de aguas limpias

allí donde el pudor se detiene asustado.

y silenciosamente similares.

Invocation

Searching for an unemployed lover1

with its air contaminated by tourists

and uncommon dissidents

where the young offer of a dress tightly fitting

the circumstances of the latest fashion trots ironically

along the sea front

among seemingly exotic cocktails

and the perennial indifference of a commissar

also confused when it comes to persuasion.

Havana was there mine and more sensual than usual

leaning out as always from her balconies

gazing tirelessly towards the sea of girls and boys of the past

dressed in lycra and the reflection of a forbidden disco

with that dizzy silhouette

facing a pale face unexpected and unknown

wearing foreign clothes, of course.

there is no time to lose for the poor beggar

searching for the right moment for a quick feel

and the game between tongues.

After all

we are in the presence of an age tormented by so many ailments.

because tomorrow afternoon would already be tonight

and also another peaceful dawn

rewarded with a sumptuous supper of simply a supper

with no imported frills

for as long as the reign of austerity lasts

or just a daring invitation.

the solitary African conch who predicts ill omens

restlessly roams the earth thirsting for so many kind acts

wasted

incoherent offerings and sullied pleas

something is wanting in the look

like that aimed at assisting the needy

so much that today Monday seems to exude a certain arrogance

which was never before entirely rational.

O mío Queen of the Sea

You who dare to ride the waves mounted on Taurus

among precious turquoise gems which adorn gentle crown

You who are always ignore the secretly agreed cry of the initiate

before dusk and you keep going in my arms

accompanied only by the sound of dry coconuts

which have always been dry.

You did not return from the grand feast

and were speaking with yourself

endeavoring to satisfy the freshness of honey

on the tips of yours breasts

your body writhing fresh with clean waters

there where shame halts frightened.

were innocent and silently similar.

Note

Chapter 1

Nobody’s Mammy

Yemayá as Fierce Foremother in Afro-Cuban Religions

Yemayá and Regla in Afro-Cuban Tradition

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations and Other Media

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Terminology and Orthography

- Introduction: Introducing Yemoja

- Part 1: Yemoja, Gender, and Sexuality

- Part 2: Yemoja’s Aesthetics: Creative Expression in Diaspora

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- Back Cover