![]()

1

The Rural Ethnic as Political Projects

Development’s Storied Edges

The bus threaded through layers of terraced lands. The field was so lush and green that the color seemed to have condensed into liquid drops striving to press a permanent imprint on my body. Outside in the scorching sun, newly planted rice was growing long and strong. With occasional gusts of wind, the tall, thin sprouts were blown toward the roadside, as if gracious hosts craning their necks in anxious anticipation of guests. From time to time, an unwieldy eighteen-wheel truck would honk by in anxious haste, loaded with sand and gravel, churning up dust storms to blur my vision of the summer fields. It was early July of 2009. The construction of an inter-provincial railroad and a highway, which meandered through villages in Qiandongnan toward the coastline, was in full force. Patches of exposed earth were visible at a distance: they used to be farmlands and were now expropriated for the road construction. As the bus wound up and down the mountain road, it was interlaced with passing clusters of wooden abodes, thatched huts, and occasionally, brick houses; bent figures dotted the summer fields and blended into a distance of green.

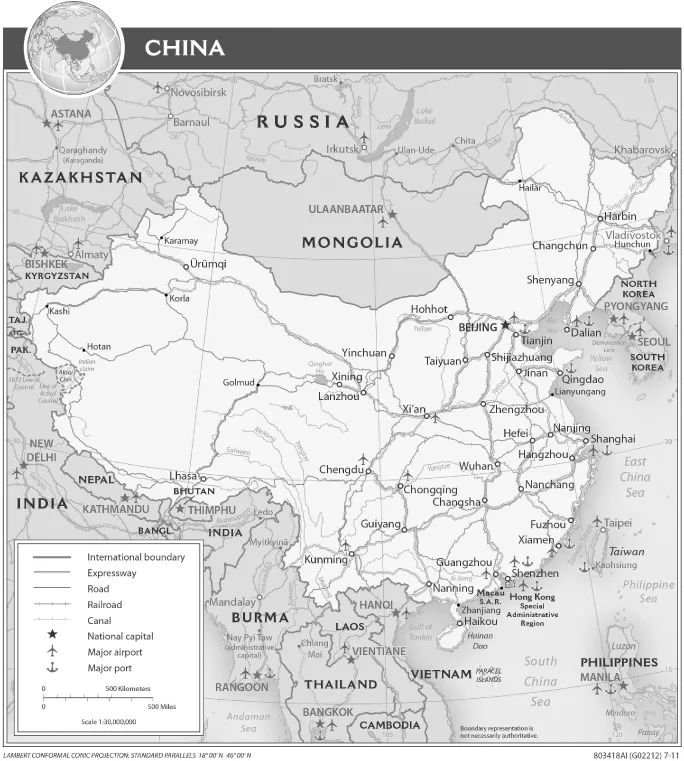

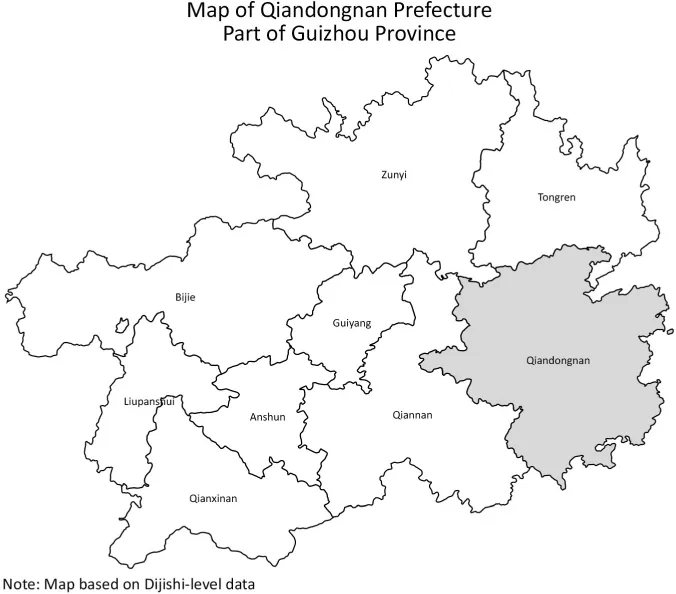

During my sixteen months of sojourn in Qiandongnan, the Miao and Dong Autonomous Prefecture in Southeast Guizhou Province (see figures 1.1 and 1.2), I shared numerous bus rides (short- or long-distance) with the mountain dwellers. The rides were usually chaotic yet vibrant, full of loud chatter and laughter, cigarette smoke, and blaring techno music. On this humid summer day, passengers were getting restless in the bus. The sticky, subtropical air assailed every inch of skin, leaving trails of perspiration on faces, backs, and palms. Men rolled up their pants and sleeves, women took off headscarves to wipe their faces, kids produced handfuls of sunflower seeds to crack off the boredom. Loaded with passengers who carried bags, buckets, reed-basins, shoulder poles, poultry, and babies, the bus made frequent stops in designated village-hamlets, or anywhere at the yell of caiyijiao (passengers’ request to “step on the brake”). Each stop generated a flurry of activities—women scurrying off with crying babies and flapping chickens, men loudly greeting those standing on the roadside, the driver climbing on the bus roof to excavate sacks and boxes, vendors peddling fruits, corn, or stinky tofu to hungry passengers, and eager faces digging for packages sent by relatives from other points along the way. Soon, the door would slide closed, and the bus would chug along with the weight of people, luggage, livestock, and delivery packages for the remainder of its journey.

FIGURE 1.1. Map of China. Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, the University of Texas at Austin.

FIGURE 1.2. Map of Guizhou, showing Qiandongnan Prefecture (shaded). Map by Yisu Zhou.

Traveling in Qiandongnan is indeed a sensory-laden experience. The landscape is at once breathtaking and precarious. Roads are roughly paved and full of potholes; landslides are frequent during rainy seasons. Many of the roads’ sharp twists and turns are littered with carcasses of wrecked vehicles—buses, trucks, motorcycles—which, for various reasons, had failed to negotiate the steep mountain grades. The sight of such deadly scenes often makes one’s heart miss a beat, adding to the popular perception that life in Guizhou, the province known as the “Kingdom of Mountains,” is fraught with danger, vertigo, and uncertainty.

Indeed, first-time travelers in Qiandongnan may find their experience colored by a variety of labels—“rugged,” “exotic,” “primitive”—that are associated with classic “out-of-the-way” places (Tsing 1993). Traveling in this region can be a highly unpredictable event, depending on weather, road conditions, and erratic bus schedules. Surrounded by a serene atmosphere, the Miao and Dong villages often exhibit a sense of timelessness to the tourists’ gaze: women sitting on narrow calf-high wooden benches doing embroidery, old men lounging on a roofed bridge smoking pipes to kill time, women beating indigo-dyed cloth with a wooden hammer to even out the color, steaming glutinous rice being beaten with long wooden hammers into fragrant baba (粑粑) (see figures 1.3, 1.4, and 1.5). Yet, while urban tourists bounce on the broken seats inside the packed bus along the potholed mountain roads, they are also overwhelmed by the bright, raucous, and pulsating world of everyday life: sensational music videos blaring from the mounted TV in the bus; printed advertisements on seatbacks for spas, massage salons, and nightclubs; satellite dishes sprouting on rooftops; ubiquitous mobile phones on the hands of young and old. As the multi-strand narratives and consumption ethos seep into daily life, a vision of Qiandongnan as bucolic, pristine, and unchanging is no longer (if ever) an accurate depiction.

FIGURE 1.3. Miao women gathered to embroider elaborate patterns on colorful cloth. Photograph by Jinting Wu.

FIGURE 1.4. An elderly woman beating a stack of cloth to even out the indigo dye. Photograph by Jinting Wu.

FIGURE 1.5. Villagers beating glutinous rice in a wooden basin to make a local dessert baba. Photograph by Jinting Wu.

On the other hand, Guizhou is depicted in a proverb as a province “without three li of flat land, three days of fine weather, or three cents to rub together.” The language of poverty, isolation, and stagnation prevails in popular narratives and social science reports and forms a set of normative representations through which places like Guizhou and Qiandongnan are imagined. Yet, even though Qiandongnan bears the earmark of “traditional” cultural practices, including subsistence farming, spirit worship, and gift giving; even though such practices have been repeated through generations, each repetition is a difference that haunts the straight line of the developmental ideology. With people, goods, and information traveling along the zigzag country roads, the dense network of communities and kinships in Qiandongnan are imbricated into the modalities of a translocal China.

The countryside symbolizes the society’s deepest aspirations, conundrums, and desires. Traveling in Qiandongnan, one is frequently greeted by roadside bulletin boards printed with enlarged messages, such as “Today’s education is tomorrow’s economy;” “Fewer and superior births bring a lifetime of happiness;” “Developing rural tourism, building a new socialist countryside.” These signs hint at the heightened salience of rural issues—including but not limited to education, birth planning, and tourism promotion—in the reimagining of the countryside and the remaking of the Chinese nation. The salience is bolstered by the popular image of the rural residents as having lower education attainment, greater inclination to have more children, and lacking market entrepreneurialism. Slogans written in such didactic vein are hyper-visible across the countryside, as a literal extension of the rural landscape shaping the materiality of the everyday. They work to incorporate the people in Qiandongnan into an assemblage of governmental discourses and under the virtual roof of the “modern.”

More than three decades after the implementation of the reform and open-door policy, China has transformed from an agricultural country to a primarily urban and industrial society. In 2014, almost 53.7 percent of Chinese are living in cities, a fast growing percentage compared to 9 percent at the beginning of the 1980s (see Roberts 2014; Deng et al. 2009). Rapid urbanization and urban-centered development churn up massive flows of rural-to-urban migration, turning the countryside into a backyard of surplus labor for China’s manufacturing boom. At the same time, ethnic and rural identities are continually (re)appropriated for economic imperatives such as tourism. The “rural” is, to borrow Phillips’s insight (2009, 17–18), not simply a marginality situated at the edge, but at the very heart of the national imaginary.

It is against such a background that this book sets out to examine the dilemmas of education at a crossroads of development and “emaciation of the rural” (Yan 2008, 25–52). In particular, the book seeks to situate rural education—upheld as the ticket out of poverty—at the center of the analysis and unravel its polemic relationships with state rural revitalization agendas, audit culture, tourism, and translocal labor migration in two village-towns of Qiandongnan. It illustrates how schooling is lived in everyday predicaments and maneuvers and is deeply entangled with other rural governing strategies. I explore the fraught experiences of village students, teachers, and residents as they juggle amorphous, disjointed, and contradictory processes that constitute the broader ecology of rural China.

The escalating educational obstacles, especially among rural population, have been widely recognized as a chief challenge facing the reform-era Chinese state (Lou 2010; Wang 2013; Maslak et al. 2010; Hannum and Park 2002; Davison and Adams 2013; Ross and Lou 2014). Education in tandem with other state modernization agendas constitutes a significant nexus of power that orchestrates social changes while engendering pedagogical, economic, and cultural debates in rural China. As China becomes the success story of education in the global arena, its rural education provides a physical and symbolic lens to examine the complex pedagogical struggles at the margin, and the making of new postsocialist rural subjects.

The central puzzle I seek to address is this: how do we understand the profound disenchantment and high attrition rates among rural ethnic youth, despites the nationwide educational desire for success, despite the state’s relentless efforts to enforce compulsory basic education, and despite the century-old folk belief in “jumping out of the village gate and into scholar-officialdom through academic success”? My study approaches this puzzle with a series of related questions: (1) What kinds of pedagogical battles are being waged on the site of the school, where the cultivation of the rural ethnic child is purported to take place? (2) How do government schools in rural ethnic settings continually fail to achieve their raison d’être yet maintain cultural legitimacy, despite the contradictions in their daily practices? (3) What overlapping processes coexist with the struggles within the schools and how disenchantment inside and outside the schools reflect and reinforce each other? (4) What are students’ life trajectories after they graduate or drop out, when the school walls crumble, to speak metaphorically?

Conceptual Issues: Theorizing Modernity, Subalternity, and Nation-State

The intersection of three major conceptual issues forms the basis of my inquiry: modernity, subalternity, and nation-state. Education, state-ordered schooling more precisely, sits at a crossroads of such conceptual matrix: it is often deployed by the nation-state as the impetus of modernity and the remover of subalternity (be it economic, social, or cultural), while simultaneously producing new forms of exclusion and marginality. The major analytical onus of this project is to tease out schooling’s entanglement in China’s modernist projects that bear upon its subaltern rural ethnic “other,” through which new forms of othering and alterity arise.

Modernity is a vague and tirelessly debated concept. Many scholars have grappled with its (dis)enchantment, challenged it for being static, ahistorical, and teleological (Gaonkar 2001; Schein 1999, Rofel 1999; Abu-Lughod 2005; Hirschkind 2006), and as the spurious child of Western capitalist domination. Regarded as a lure rather than a threat, modernity is said to have spread across the globe over the longue durée of transcontinental contacts, “transported through commerce, administered by empires, bearing colonial inscriptions, propelled by nationalism, and now increasingly steered by global media, migration, and capital” (Gaonkar 2001, 1). This echoes Ong’s indictment of the academic assumption that “the West invented modernity and other modernities are derivative and second-hand” (1996, 61).

Criticized as a crippled term, the concept of modernity is charged with reducing the differentiated, relational, and dynamic sociohistorical processes to pure instrumentality, for flattening multiplicities to a linear, historicist development trajectory. Postcolonial scholar Dipesh Chakrabarty (2000), for instance, in his study of Hindu Bengalese in northern India, provokes an intriguing sense of conundrum in the formation of Bengali modernity. On the one hand, he invites a reconsidering of whether it is possible to write any kind of history that does not index back to European modernity as the birthplace. On the other hand, Chakrabarty argues that the homogenizing claim of modernity is as much a yet-to-come as already embedded in local everyday experiences that both advance modernist values and perpetuate its antithesis.

Similarly, the unidirectional and univocal narrative of modernity is hardly sustainable in China, which has oscillated between the periphery and the center in its global influence and undergone multiple centers and peripheries within. The meaning of modernity in the Chinese context is intertwined with China as a geopolitical concept and a changing sociocultural landscape. From China’s first convulsive encounters with Western powers during the Opium Wars (1839–1842; 1856–1860) to the May Fourth Movement (1919)’s campaign for “science” and “democracy,” from the devastating years of the Great Leap Forward (1956–1958) and the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) to almost four decades of post-reform economic boom, the Chinese nation has always positioned itself within ongoing debates regarding tradition, reform, development, and modernization.

Specifically, the dramatic social changes over China’s long twentieth century have made modernity a recurring yet elusive figure. From isolationism to open-door policy, from communism to socialist-capitalism, from planned economy to market liberalization, China rehearses its idiosyncratic linear narrative of “backwardness” to “progress,” with each subsequent era approaching, but never quite arriving at what Lisa Rofel (1999) describes as a modernity perpetually deferred. If China’s embrace of modernization indicates reflexivity over its off-centered positioning on the global stage, its “holdout” population—the rural ethnic “other”—provides an internal anchor for its modernist aspiration.

The desire to uplift the “holdout” population on par with the putatively more modernized Mandarin-speaking Han Chinese, who are simultaneously looking toward the West as standard-bearers of the modern, produces a double current of Chinese modernization. This double current is mediated by wider forms of geo- and cultural politics both inside and outside China, and further complicated by China’s endeavor to steer clear of an “undifferentiated global modernity” by claiming unique Chinese characteristics, yet at times remain virtually unintelligible outside the China–West binary.

I arrived in Guizhou in early 2009 to begin my sixteen-month-long fieldwork. The worldwide financial crisis begun the previous year had damaged many national economies, but not the confidence of the Chinese lawmakers. The rest of the world, once again, watched China in its soft-landing and relatively speedy recovery from the global financial downturn. In both interviews and casual conversations, the Guizhounese seemed less bothered by the financial crisis but exhibited a decidedly future-oriented momentum of “getting ahead.” Development became a ubiquitous descriptor across the social landscape of Qiandongnan at the time of my stay, dehistoricizing and mystifying the uncertainties of local life by implying a condition of normalcy and predictability. Tourism programs were swiftly underway in many villag...