![]()

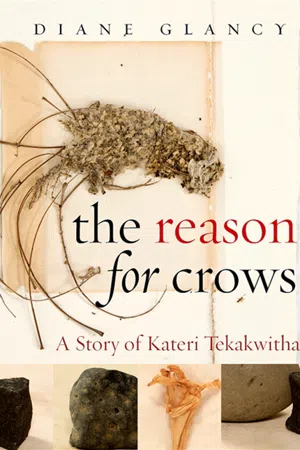

The Reason for Crows: KATERI TEKAKWITHA

1656–1680

MOHAWK / ALGONQUIN

KATERI TEKAKWITHA

—Unto thee O Lord I commendeth my soule.

KATERI: The moaning was my first memory. I think it was them—my mother and father. They died in the smallpox epidemic with my infant brother. I was five years old. Black birds gathered waiting for our death. I felt the birds peck my face. In my fever dream, I was floating in a stream. A Spirit lowered its basket to gather water. I was in the water that spilled into the basket. For a while, I was inside God. I floated like a crow.

My mother was Algonquin. My father, a Mohawk chief. I was born in a village called Ossernenon on the south bank of the Mohawk River. My mother was a Christian. My father was not.

The smallpox left its encampment. My parents and brother were gone, though I still had relatives. Children laughed when I passed. Boys turned away from my face. I am not a saint. I am a girl seeking sanctuary. I am scarred. I feel the pits on my face with my fingers. My eyesight is bad—I can look into the woods and see snow that is not there. The shapes of the trees are blurred. This toxic God. This Fire who burns away everything.

I see lions when I sleep. I did not know what a lion was until I saw one in a book in the mission. They have eaten Christians. They are magnificent in their roaring. Jesus is a lion. I often see him with a mane of light.

Smallpox is a crow. Its black wings like the night. Its beak eats my face. If black were an object, it would be water. The way it shapes the rocks in its path.

My name, Tekakwitha, means the one-who-walks-groping-her-way. Or moving-all-things-before-her. It means one-who-puts-things-in-order. Or one-who-bumps-into-things. It is a name that can go several ways. It can have several meanings. But they all have to do with seeing what is before me. Smallpox nearly took my eyesight. I trip my way through the village. Especially in bright light. I see snow— I have said that. But it repeats itself also.

I hardly remember the earth before it blurred.

Is it the same for all who hear the Lord’s voice? Mine came with smallpox. The fever of fire. My mother heard the Jesuit’s words. She knew the wings. She was given as a wife to a chief who did not believe. She kept her belief. It was a story she carried. A direction she followed. A map she kept through this crow-dark woods.

She taught me faith in Jesus. She belonged to the Maker the Jesuits called God. He sent his son, Jesus, to become a crow on the cross. He became darkness for us. I made crosses with sticks and left them in the woods—tying them at the cross-arms with animal hair or sinew. I tell the rabbits and muskrats about Jesus. Suffering is for a benefit— We come to knowledge of You, O Lord. The animals listen.

My chest is burning. I am nearly blind in the sun. I am pocked.

Lead us through this wilderness of crows. I cry out to you—You are my way. Under your wings I make my refuge until these calamities pass—Psalm 57:1–2. I am drawn to that Psalm. It is a tree standing by itself. It is a copse. It is the voices of the forest shouting.

My mother was an Algonquin Christian of the Weskarini or turtle band. She was taken prisoner by the Mohawk—married to the chief of a tribe different than hers. I do not think she minded being with my father. She seemed happy. But I was young when she died. It might have been different than I knew. My father died in the epidemic with her. Also my brother.

Then my uncle, Iowerano, was chief. I was adopted by his wife, Karitha, and his sister, Aronsen. The women were Christians also.

I was scarred with smallpox, yet I made ribbons from strips of eel skin and painted them red. I tied them in my hair.

I picked corn with my uncle’s wife and sister, sometimes holding one hand over my eyes when the light of the sun hurt them. I listened to the forest. The noise of birds as they called to one another. I listened to the wind through the leaves, the water in the rivulets and the river. It was sound I saw.

I carried small bundles of firewood from the forest with the tumpline—the burden strap on my head—I wove the strap with threads from bark strips, threaded and woven together until the stay was strong enough to haul the load of twigs.

I carried water in a small bark bucket. I pounded corn. I could not do the work of other girls and women. I trembled. I sweated. I felt the smallpox again. Or the remains of it. I lay shivering on my mat in the dark of the longhouse until I could get up again.

Anastasia Tegonhatsiongo and Enit stayed with me. They were older sisters, friends. Anastasia was a widow. Enit knew she would marry Onas. She talked of him as we worked. I did not think I would ever talk of marriage. I beaded with them, feeling my way with the bone needle and sinew. I remembered the patterns of the beads with my fingers. I felt I could see when I beaded. We had as many beads as the stars.

We made baskets, boxes, buckets, and large bark casks rimmed with hickory splints to store corn, berries, beans.

We treated the wounded when the Machicans attacked our men who were hunting. Often, not many were left alive. We listened to their moans. I think sometimes the spirits suffocated them, helping them leave their wounds in this world. Once, in the dark, I put my hand on something wet and sticky. I felt it again and knew it was hair. It was the scalp of someone dying, not fully severed from his head.

We wove belts to trade for thimbles, glass beads, iron awls, pewter spoons, bells, muskets, lead shots, knives, and nails.

It was the thimbles and glass beads I wanted. The thimbles more than the glass beads.

The smallpox continued. It moved among tribes. We heard of it from a distance. We saw it in our own village. It began with fatigue. Someone could not climb a tree for bird eggs. Then there was nothing they wanted to do. Or could do. Then fever. Headache. Backache. Vomiting. Red spots appeared on the tongue like berries. Then the spots moved to the mouth and throat. The spots turned to blisters. The blisters covered the face. The arms. Legs. Palms of hands. Soles of feet. They were under the eyelids. Joints swelled. There was bleeding. Terrible dreams. Delirium. Pustules crusted over the whole body. Death.

Now I wear a blanket over my head to hide my eyes from the light. But mostly I wear it to cover my pocked face.

I am not able to help those who are sick with smallpox. I am not yet strong enough to turn them on their mats. But I can wipe their sores. Sit beside them. Fan them. The forest holds us in its teeth.

The forest is a lion.

After a few years, the tribe moved upstream, to a hill above the north bank of the Mohawk River to get away from the place of the moaning disease that killed my parents and brother. I hear the forest moan also. I think sometimes it has the disease. I hold the leaves with my fingers. They feel pocked. Maybe the forest suffers what we suffer. Maybe it becomes like us. It is marked like we are marked. It feels what we feel. We are one with it.

I held the hands of Karitha and Aronsen, the wife and sister of my uncle, Iowerano, the chief, as we descended the hill from the old village. They helped me step into the canoe that would take us across the Mohawk River.

We climbed the hill on the other side of the water with our bundles. The sachems blessed the place of the new village. We built longhouses and plant crops. We named the new village Caughnawaga. We marked hiding places in the woods in case of attack.

Sometimes I tremble in the forest. It is the aftermath of the disease. Why do some of us stay on earth, while some of us sit in heaven where the falling stars whiz past?

Sometimes I wake sweating. I wake from the forest dreams when the evil one lurks. I see the trees move where he passes. I hear his roar that lifts through the trees. He is not a lion, but he thinks he is. I often think how the forest is like our Christ. It is stronger than the evil that passes.

I hurt my foot when I tripped over a stump at the edge of the forest. I had a bundle of twigs in my bundle strap. I fell and turned my ankle. My twigs scattered. When I got up, I could not stand. I could not walk. I crawled back to the village. For a long time, I lay on my mat. When I could get up, I limped. I am nearly blind. The light is sharp in my eyes. Sometimes the air swirls before my eyes. I watch it turn over. My face is scarred with smallpox. Yet there is a ribbon of red eel skin in my hair.

There is a commotion outside the longhouse.

I hear the voice of Onas, whom Enit thinks she will marry. He is warning us—Run to the woods. What is happening? I cannot see. I do not know anything until it is upon me. Who is coming? The Machicans? Our enemy tribe? No, this time it is the French soldiers. Often we fear them.

I hear them coming, rattling their guns over the land. I run with others into the woods, Anastasia and Enit now holding my hands, pulling me along because I cannot see the way in my fear. We hide in places the soldiers do not know. We hear shots from their guns. Enit cries out for Onas. Anastasia tells her to be quiet. We hear the crackle of fire. The smell of smoke. I grow dizzy—trees lean over—the sky is slanted. I hear the moan of the flames in our crops. I hear the cries of the corn and beans as they burn.

When Onas calls, Enit runs to him, leaving a hollow place at my side. Maybe the Maker was there, and I just could not feel him. I returned with Anastasia to the village in rubble. The blur I see is the smoke still rising from the ruins of the bark longhouses. The crow wings I see are our burned fields.

The soldiers have destroyed our new village on the north bank of the Mohawk. They have burned all of the crops we planted. The new longhouses we built. Everything is burned. Our woven mats. Our moose-hair and quill work. Our burden straps. Our fish weirs for catching eel. The bow loom to weave wampum belts.

Later, we walk through the ashes. We find the melted glass beads and thimbles. I feel them with my feet. I keep a charred thimble warped from its shape.

Because there are no crops, we are hungry that winter. Anastasia, Enit, and I put on our snowshoes and go into the woods with our digging sticks. We gather roots. We boil bark. We pound acorns mixed with a few dried berries. Once, there was an animal to eat, half dead itself before we killed it. Sometimes there was nothing.

It was in the winter that Enit married Onas Sangorkaskan. My Uncle Iowerano spoke the ceremony. A wooden bench was placed in the center of the longhouse where Enit and Onas sat, each holding their wedding basket they would exchange. I heard my uncle’s voice to Enit and her family. What is her name? What clan? Do you accept your daughter’s choice? Will you prepare food? Then he directed questions to Onas. Will you provide food? Afterward they exchanged the wampum.

But even when Enit married, we still had little to eat. The hunters returned discouraged. I think it was shame they felt. We had known hunger, but this hunger seemed more severe. We were up against something new. There was a shift in the land. Its voice was troubled. We heard it in the trees. We heard it in the night, the underside of day, when the hunters and night stalkers were out. We used to hear the larger animals that killed the smaller ones. Now it was the cries of the stalked we heard. We felt their fear. The night was embroidered with worms, bugs, burrowers. It was stained with blood. The overside was day. But the trouble of the night stayed with us.

Priests came to the village, but left. Were they the ones that had converted my mother? They sounded like her—they told stories I had heard from her. There was the same feeling—the same spirit. We had seen the traders and trappers. Our dreams were a village where they passed. Now we heard about the settlers. They came from other lands. They came to live where we did. Why had this happened? Why had they left their land and walked across the water in a boat? But did Indian tribes not migrate and drive out other tribes?

Karitha, my uncle’s wife, and Aronsen, his sister, grieved.

We will be given to the crows, they s...