JASON E. LANE

ABSTRACT

Multi-campus higher education systems in the U.S. developed during the 20th century. They began as a way for states to oversee their several public colleges and universities. By the middle of the last century, they started to develop prominent roles as coordinators, regulators, and allocators. However, the structures and roles of the past are not necessarily the best way to contend with current demands and environmental constraints on public higher education. Some systems have begun to explore ways to steer their constituent campuses to advance the needs of their state and to identify new ways to support and serve the campuses—that is, add value to internal and external stakeholders. This concept of adding value is a core dimension of higher education system 3.0. This chapter provides a broad overview of the development and current status of multi-campus higher education systems, briefly examines the literature on the topic, and provides readers with an orientation to the structure of the volume.

In November 2012 a very unusual weather pattern formed off the east coast of the United States. Superstorm Sandy, a super-charged hurricane, traveled up the eastern seaboard, making a sudden turn inland around New York City, bringing high-powered winds, dramatic water surges, and significant amounts of rain. It proved to be one of the most destructive natural disasters in the region's history, with estimates as high as $42 billion in damages for New York State alone. The widespread damage caused by the storm proved that New York's physical and administrative infrastructure needed significant investment to better mitigate the impact of similar catastrophic events in the future.

In the following weeks, New York governor Andrew Cuomo created the NYS 2100 Commission to assess the resilience and strength of the state's infrastructure and identify ways to enhance that infrastructure to deal with natural disasters and other emergencies. The commission was co-chaired by the head of the Rockefeller Foundation, which provided financial and administrative support to the commission. However, despite the wide range of expertise brought by the varied commissioners and the Rockefeller Foundation, the governor's staff recognized that for any effort of this nature to have a meaningful impact, the engagement of cutting-edge scientists and researchers would be required. Identifying the right individuals was a daunting task, because a natural disaster such as Sandy crossed many areas of study, including engineering, environmental studies, energy, finance, insurance, and public policy.

To find these experts, the governor's office turned to its state university system. The State University of New York's (SUNY) vice chancellor of research worked with administrators at the constituent campuses1 to identify experts across the system. Ultimately, they developed a team of experts of more than 20 scientists and researchers from five of the system's campuses. These experts worked collaboratively with the commission's subcommittees to provide information about cutting-edge research and helped to develop the recommendations that formed the final report that would guide New York's natural disaster preparedness.

The situation described here demonstrates the value that higher education systems can add to states, as well as to their constituent campuses and faculties. The state was in need of research-based expertise to help it devise a plan to secure the health, well-being, and prosperity of its citizens in the future. The state could have sent out a general call for assistance or reached out to one or two institutions in the hope that they could provide some assistance. However, those staffing the NYS 2100 Commission had limited time and knowledge, making it difficult for them to find the right people in the short time they had. Thus, they reached out to SUNY, which was able to quickly mobilize faculty members from across the system to provide the required assistance.

From a campus and faculty perspective, there is also value in this scenario to being a part of the system. If no system existed, or had the state reached out to individual campuses on its own, it is likely that some members of the team would have still been identified to engage in the work of the commission. However, assistance from the system office likely created a stronger team of experts as it drew on expertise across the entire system. Thus, individual campuses and faculty members were given the opportunity to use their knowledge and resources in a way that could have significant real-world impact. The exercise proved successful enough that the team of experts began looking for ways to continue their collaboration beyond their work for the commission.

This enhanced collaboration, or systemness as SUNY chancellor Nancy L. Zimpher refers to it in chapter 2, is the key aspect of version 3.0 of higher education systems. That is, to be successful in the future, higher education systems need to move beyond their roles as allocators, coordinators, and regulators. They need to exert leadership in moving higher education institutions toward greater impact in their societies. They need to identify and pursue ways that add value to the states they serve and the campuses of which they are comprised. In moving toward systemness, higher education systems need to find ways to (1) promote the vibrancy of individual institutions by supporting their unique missions; (2) focus on smart growth by coordinating the work of campuses to improve access, control costs, and enhance productivity across the system; and (3) leverage the collective strengths of institutions to benefit the states and communities served by the system.

However, it is also important to be realistic about the environment in which systems exist. They face several challenges to harnessing systemness. Tensions often exist between “flagship” institutions and other colleges and universities within the system. Systems need to balance the needs of disparate institution types and geographically dispersed campuses. System governing boards are charged with protecting the interests of the state and ensuring the financial stability and academic quality of the institutions in their care. Sustained reduction in public funding over the recent years has caused systems and their constituent campuses to identify other sources of revenue to maintain their quality. Finally, the Great Recession has forced systems to reconsider a host of operational issues as they have sought to address issues of access, cost, and productivity.

This chapter sets the stage for the rest of this volume. The chapter begins with a brief discussion of the environmental factors affecting higher education and why now is an opportune time for higher education systems to reform themselves in ways that will provide enhanced value to their states and constituent campuses. Subsequently, I examine the reach of higher education systems in the United States, including the fact that they exist in a majority of states and serve a large proportion of the nation's college students. Next, the inherent tensions of higher education systems are discussed, along with new ways in which systems can create value for their various stakeholders. The chapter concludes by outlining a research agenda for the future study of higher education systems.

IN SEARCH OF HIGHER EDUCATION SYSTEM 3.0

This volume focuses on the remaking of the governance, administration, and mission of higher education systems in an era of expectations for increased accountability, greater calls for productivity, and intensifying fiscal austerity. Higher education systems were first created as a means for facilitating state oversight of vastly decentralized public higher education sectors. In the 1960s and 1970s, systems began to focus also on ensuring effective use of state resources, such as controlling the duplication of academic programs. More recently, however, there has been a concerted effort by system heads to identify ways to harness the collective contributions of their various institutions to benefit the students, communities, and other stakeholders whom they serve. Higher Education Systems 3.0 explores some of the recent dynamics of higher education systems, focusing particularly on how systems are now working to improve their effectiveness in educating students and improving communities, while also identifying new means for operating more efficiently.

In the 21st century, public higher education is confronting a number of challenges. The funding provided by many states has stagnated or is diminishing. Demand for access to higher education is expanding, particularly among populations that have not typically pursued formal education beyond the high school diploma. Many students are now swirling through the postsecondary experience, taking courses from a wide variety of institutions (McCormick, 2003). Online educational provision has achieved widespread legitimacy, with even Ivy League institutions making significant investments in these endeavors and broadening their reach to thousands of new students (Lewin, 2012; Pappano, 2012). Finally, the world has flattened, necessitating that colleges and universities explore new ways to become internationally engaged and to prepare their students to be competitive in a global marketplace (Friedman, 2005).

Moreover, state governments are increasingly questioning the return on their investment in higher education. On one hand, they are having to find ways to balance state budgets—a difficult task given the skyrocketing costs for the health care and prison systems and, for most states, declining revenues following the Great Recession of 2008 (Zumeta & Kinne, 2011). On the other hand, states have had to respond to their constituents, who are decrying the rapidly rising cost of postsecondary education. Thus, higher education officials have had to be more active in evidencing the value that their institutions bring to their students and the communities in which they exist.

The environment in which higher education institutions now operate necessitates a reexamination of the structures that guide and govern their activities. For most public colleges and universities, this means focusing on the systems in which they operate. In the United States, responsibility for education falls to the state, meaning that there is no central education ministry or department that controls education across the nation.2 As such, each state needed to develop a way to govern and administer its public colleges and universities. At first, many states followed the model of private institutions and developed lay governing boards for each of their public institutions (Duryea, 2000). However, in the 20th century, concerns began to arise about the lack of coordination among public institutions, the undue political influence some elected officials were trying to exert over individual institutions, and the increasing competition for resources (i.e., requests for state appropriations) from individual institutions (see chapter 3).

To alleviate these concerns, many states created higher education systems, overseen by comprehensive governance and administrative structures that were situated between the institutions and the state government. To be clear, in this book the focus is mostly on the multi-campus system. One of the more common definitions has been developed by the National Association of System Heads (NASH, 2011):

A public higher education system [is] a group of two or more colleges or universities, each having substantial autonomy and headed by a chief executive or operating officer, all under a single governing board which is served by a system chief executive officer who is not also the chief executive officer of any of the system's institutions.

Such systems are different from a university structure wherein there is one flagship campus and a number of branch campuses.3 It also does not refer to a coordinating board structure, where there is a state agency with some authority over higher education, but each institution is governed by its own governing board.4 However, the tensions, visions, and new directions discussed in this volume are not limited to multi-campus systems. Many of the lessons from the varied contributions are relevant to other configurations where multiple campuses work together.

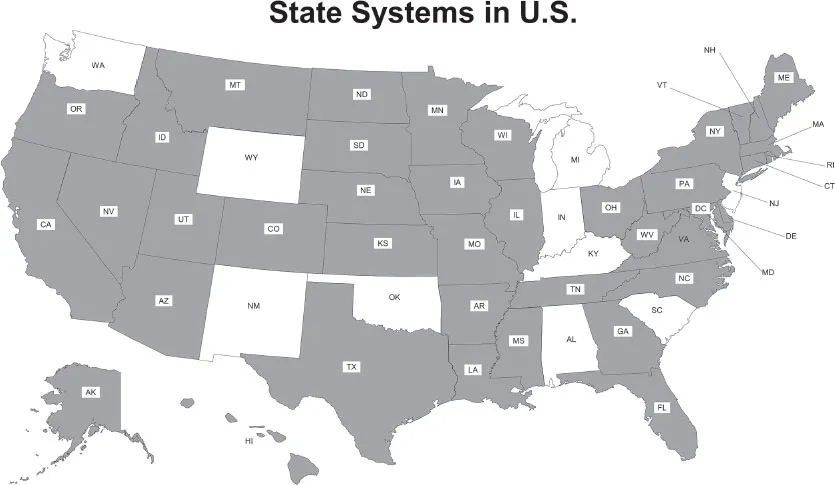

Multi-campus higher education systems are a primary component of the higher education landscape in the United States. At the time of this writing, the National Association of System Heads (2011) reported that there existed 51 multi-campus systems in the United States, spread across 38 states (see figure 1.1).5 In academic year 2011, they collectively served more than six million students–approximately 30% of all postsecondary students in the United States and more than 40% of all students studying in public higher education.6 Moreover, many of the leading public research universities are part of these higher education systems.

There are generally two types of multi-campus systems: segmented and comprehensive. The 23-campus California State University (CSU) system, created in 1961, is considered a segmented style system as all the campuses are similar in terms of mission and academic degrees offered (Gerth, 2010). The CSU system was created to provide broad access to higher education for the citizens of California and currently enrolls more than 400,000 students per year. The SUNY system, founded in 1948, is comprised of 64 campuses and serves more than 450,000 students annually (Leslie, Clark, & O'Brien, 2012. It is considered a comprehensive system, as it includes different institutional types, including community colleges, comprehensive colleges, research universities, and several special focus institutions.

Figure 1.1. States (in gray) with Public Multi-Campus Systems

Source: National Association of System Heads (2011)

The role of these systems has historically been to provide a level of coordination among the campuses, allocate funding from the state to the campuses, enact and enforce regulations, serve as a common voice for higher education to the state government, and communicate the needs of the state to the campuses (Lee & Bowen, 1971; Millett, 1984). However, while the existence of systems was acknowledged, many institutional leaders and scholars of higher education governance continued to emphasize the importance of individual institutions and the criticality of institutional autonomy (Corson, 1975; Millett, 1984).

This view was often reinforced as system structures evolved as a type of organization different from an in...