![]()

chapter one

WHY A SCIENCE OF COMPLEXITY?

“Quarks are simple but jaguars are complex,” explained the Nobel laureate in physics and pioneer in complexity science Murray Gell-Mann (1994). So too, the inner workings of a cell in a worm are more complex than those of the sun. A survey of particle physics research finds that the “universe is a complex and intricate place” (Lincoln 2012).

Humans are even more complex than worms or jaguars—especially in world affairs as individuals and groups of humans deal with one another across borders of culture, language, politics, and geography. As Ralph Waldo Emerson put it 1847, “The last lesson of modern science is that the highest simplicity of structure is produced, not by few elements, but by the highest complexity. Man is the most composite of all creatures”—quite the opposite of the wheel insect, volvox glob.

The difference between complexity and complication was made clear in an essay by Daniel Barenboim on Richard Wagner (New York Review of Books, June 20, 2013). “Wagner’s music is often complex, sometimes simple, but never complicated.” Complication implies “the use of unnecessary mechanisms or techniques that could potentially obfuscate the meaning of the music. These are not present in Wagner’s work.” By contrast, complexity in Wagner’s music is represented by multidimensionality—“many layers that may be individually simple but that constitute a complex construction when taken together.” When Wagner transforms a theme, he does so by adding dimensions. “The individual transformations are sometimes simple but never primitive. …” Wagner’s “complexity is always a means and never a goal in itself.”

Human society and culture did not just drop from the sky but, like other human activities, arose from beings and processes shaped by millions of years of evolution (Wilson 2012). Humans and the estimated seven million other animals who now roam the planet, from the ocean floor to the highest mountains, evolved from single-celled ancestors who, some eight hundred million years ago, probably resembled today’s Capsapora owczarsaki, a tentacled, amoeba-like creature barely noticed by scientists until 2002. Animal bodies can total trillions of cells, able to develop into muscles, bones, and hundreds of other kinds of tissues and cell types. From single cells arose a vast kingdom of complexity and diversity (Zimmer 2012).

Humans, however, are not just “wet robots” (Dilbert’s term) and social science is not just biology or physics. Still, those who seek to understand political life need an approach to scientific inquiry with strong links to the life and other sciences. They must consider human affairs in the context of other animate and inanimate activities across a shrinking planet.

Scientists from many disciplines now mobilize to study the most complex object in the known universe, the human brain. The brain activity mapping project sponsored by the U.S. government, starting in 2013, and conducted at several universities will study how the brain is wired at all levels—from individual nerve cells to the neuronal superhighways between its various lobes and ganglia. The project will institutionalize the emerging science of connectomics. Brain mapping and the human connectome project should shed light not only on mental processes but also on mental disease, brain injuries, and psychopathologies.

THE COMPLEXITY OF INTERDEPENDENCE

The complexity of global interdependence demands a science of complexity to fathom it. The essence of life is interdependence—every element dependent on every other. Walt Whitman depicted this reality in his Salut au Monde:

Such gliding wonders! Such sights and sounds!

Such join’d unended links, each hook’d to the next,

Each answering all, each sharing the earth with all. …

I see the shaded part on one side where the sleepers are sleeping, and the sunlit part on the other side,

I see the curious rapid change of the light and shade,

I see distant lands, as real and near to the inhabitants of them as my land is to me.

A few years before Whitman composed his Leaves of Grass, Karl Marx in 1848 described how global economics intensified the planet’s “unended links, each hook’d to the next.” And long before Thomas L. Friedman (2007) argued that The World Is Flat, the Communist Manifesto declared: “In place of the old local and national seclusion and self-sufficiency, we have intercourse in every direction, universal interdependence of nations [eine allseitige Abhängigheit der Nationen voreinander]. And as in material, so also in intellectual production. The intellectual creations of individual nations become common property. National one-sidedness and narrow-mindedness become more and more impossible, and from the numerous national and local literatures, there arises a world literature.”

The Manifesto postulated that human history is the story of class struggle rooted in a materialist dialectic. More than two millennia before Marx, Thucydides described a struggle for political hegemony that nearly destroyed the glory that was Greece. The idea that politics is dominated by zero-sum competition was set out again by Machiavelli in Renaissance Florence and by Thomas Hobbes amid England’s seventeenth-century civil war. Hobbes postulated a “war of all against all” that can be quelled only by an almighty sovereign who imposes order over anarchy. Twisting Darwin’s theory of evolution to rationalize European dominion over Africa and Asia, nineteenth-century Social Darwinists proclaimed that life is a struggle for survival and that might makes right. Jack London in the early twentieth century described life in Alaska as dog-eat-dog. Nazi geopoliticians asserted that East Europeans must give way so the master race could expand.

Contrary to Marx, to Social Darwinists, and to disciples of Ayn Rand, we now see that evolution is complex—shaped by cooperation as well as competition—between and within species (Kropotkin 1904; Minelli and Fusco 2008; Flannery 2011). The red-toothed “survival of the fittest” interpretation of evolution is much too simplistic. Humans, like other living things, often collaborate to increase their survival prospects and other interests. Scientists debate whether cooperative tendencies result from a “selfish gene” or other factors. The Nobel Prize for Economics in 1986 went to James M. Buchanan, who warned that politicians and publics seeking their own self-interest could institutionalize irresponsibility as government outlays exceeded revenue. The Nobel Prize for Economics in 2012 went to an economist and a mathematician, Alvin Roth and Lloyd Shapley, who used cooperative game theory to show how goods could be shared to mutual advantage.1

As humans specialized, society became more complex and interdependence mounted. Adam Smith posited an “invisible hand” that served the common good. This was not the whole story, however, for interdependence can cut two ways. The term denotes mutual vulnerability—a relationship so close that the parties can help or hurt one another If an actor cannot deflect the changes made by another, it is “vulnerable.” If it can thwart the change, it is merely “sensitive” (Keohane and Nye 2011). The policy implication is that the invisible hand may need guidance and even regulation.

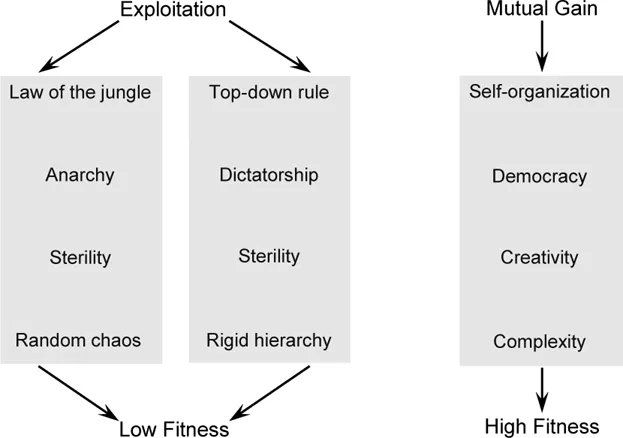

A fit society thrives on complexity and its capacity to create values from the challenges and opportunities arising from an ever-changing environment. Like a coral reef, participants in a fit society exist in a symbiosis that protects and nourishes both individuals and the wider community. Mutual gain and high fitness are the products of self-organization and creative responses to complexity. Diminished fitness, by contrast, is the consequence of a zero-sum, exploitative approach to life—the usual pattern when there is no law or rigid, top-down rule. These concepts are elaborated in later chapters, but the basic argument is summarized in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1. Exploitation, Mutual Gain, and Fitness: Likely Linkages

CHAOS OR COMPLEXITY?

The deep realities of life are difficult to discern and assess. As John Muir cautioned, “Touch one thing and you find it is linked to everything in the universe.” If a butterfly flaps her wings in China, how will this affect the next day’s weather in Kansas? As weather develops, it feeds back on itself and influences future weather. The butterfly effect underscores the interconnectedness of all things. Even if we could trace long chains of interaction, however, small errors in initial measurements would multiply and lead to erroneous conclusions. Chaos theorists conclude that the chains of cause and effect in many domains—weather, turbulent rivers, insect populations, stock markets, and others—cannot be accurately predicted. Some chaotic structures may be in principle deterministic, but in practice they are virtually unpredictable (Marshall and Zohar 1997, 81–86; Krasner 1990). A miniscule error in the initial measurement of just one variable will skew the entire calculation.

Complexity science agrees with chaos theory and worldviews such as Buddhism that all things are interdependent. But it avers—or hopes—that common patterns characterize the evolution of all things, and that, with hard work and some luck, we may identify them and begin to fathom their interactions. Thus, complexity scientists have discovered fractal properties within heartbeats as well as in stock market movements and air flow turbulence.2 They have investigated scalability. It appears that some of the same principles apply to animals of different sizes and species—even to cells. Thus, the metabolic rate is proportional to body mass in everything from a mouse to a goose to an elephant. Organisms reach a certain weight at a certain age. Or look at a forest. At first, it may seem to be a wild thicket, randomly organized, with no structure. But there is structure. A forest has trees of a certain type, size, and age—often spaced at a similar distance from each other, each consuming a similar amount of energy and growing at a similar pace. In bodies, as in entire ecosystems and in sprawling cities, networks provide basic functions that range from blood circulation to irrigation to electric transmission. The pace of life slows as size of organism increases. There are economies of scale. Cities, like organisms, seem to obey power laws of scaling. As cities expand, we see fewer gas stations per capita. With more people, the length of electric lines needed to serve each person decreases. The dynamics of life go beyond mere natural selection (West 2011).

It may appear that complexity can be reduced to regularity and simplicity. Thus, Acemoglu and Robinson (2012) studied many complex and seemingly quite different cases over time and concluded that “nations fail” because their leaders exploit the common good for private gain.3 Similarly, Emerson (1847) believed that Goethe possessed “a power to unite the detached atoms again by their own law.” Goethe contributed a key to many parts of nature through the rare turn for unity and simplicity in his mind.4

Following in the footsteps of Goethe and—before him—Leonardo Da Vinci, complexity scientists seek to identify and understand the patterns of behavior common to all forms of life.5 But many structures—from a beehive to the weather to the human brain—seem to defy any reductive approach. Isaac Newton appeared to have discovered the basic laws underlying the flux of physical motion, but Newtonian physics was later supplemented or supplanted by relativity and quantum mechanics.6 Reductionism does not work where reality breaks from linear sequencing—with outcomes not proportional to ostensible causes, and where wholes cannot be understood from analyzing their parts (Kauffman 2008).

Classical economics is also reductionist. It assumes that the real value of goods is determined by the price they fetch in the market place. Put into practice, however, this approach is unfair and conduces to huge disparities in income. Theoretically, it is untenable because one cannot know in advance what goods and what supply/demand conditions will exist. Nor, in biology, could we anticipate that from the lungs of lung fish would evolve the swim bladders that assure neutral buoyancy in the water column of certain fish—nor what kinds of creatures would find their niche within those bladders (Kauffman 2008; 2011).

THE EVOLUTION OF SOCIETAL FITNESS

A system of cooperative bands provides the social infrastructure that can nurture creativity. The social institutions and behaviors that differentiate humans from other primates developed in large part because they were enabled by biological and historical accidents. Cooperation is a key behavior that distinguishes humans from other primates. A system of cooperative bands provides the social infrastructure that nurtures human creativity. No individual can construct a rocket ship. To build and fly the International Space Station required the collaboration of thousands of persons, most of whom never met one another, and many of whom came from “tribes” with distinct languages and ways of life.

Social institutions and world affairs, like all evolution, have been decisively impacted by accidents. “Evolution is, fundamentally, a process of cumulative integration: Novel combinations of older material or otherwise ordinary features generate systems of new properties—emergent properties—which in turn promote further evolutionary change” (Chapais 2008, 303). Nothing appears to have been unidirectional or foreordained.

Biology is not physics.7 Very little in evolution was preset. Little could be prestated or anticipated. Living beings evolve in ways that defy prediction. Each step in evolution is a kind of preadaptation. Each innovation arises from and builds on what precedes it. Each creates an “enablement” or “adjacent possible” from which new adjacent possibles can emerge (Kauffman 2008). Mutant genes gave some individuals traits better adapted to survive and prosper in their environment.

The evolution of society and life itself is impossible to predict because of adjacent possibles. Each new adaptation opens the way to other innovations, as the laptop computer opened the way to iPhones and social networking—all undreamed of by those who, during World War II, sought a mechanical system to break German codes. Who could have predicted Facebook without first anticipating the invention of the Internet and then of miniature computers? We cannot prestate such innovations.

Both serendipity and synergy contribute to unforeseeable outcomes. Still, once a series of enabling conditions has conduced to a new set of conditions, one can look back and say that such-and-such factors seemed to have led to such-and-such effects. In retrospect, it seems clear that growing complexity has bred still more complexity.

Many features that make humans more adaptable than other primates and some human societies more fit than others have resulted from biological and historical accidents. Once humans learned to communicate and plan, some gained fitness by acts of cognition and volition—they made smart (or lucky) choices and tried to execute them. If we go far back in time, however, successful adaptation to a changing environment depended in large part on accident—an opportune conjunctions of self with other.

The distinctive qualities of human behavior derive from many factors. The genomes of humans and chimpanzees are 99 percent the same, but humans learned to cooperate in ways that gave them powers unknown to chimps and any other animals. How did humans—unlike other primates—learn to cooperate? The answer began four to six million years ago when the apelike creatures from which hominoids descended broke off from the ancestral line shared with chimpanzees. Some apelike creatures acquired a more human form approximately one hundred thou...