eBook - ePub

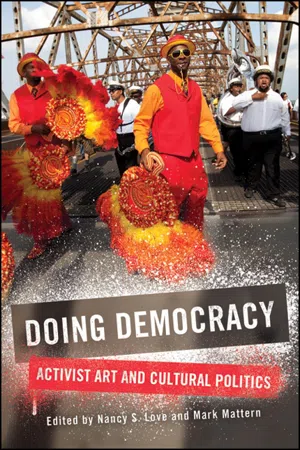

Doing Democracy

Activist Art and Cultural Politics

- 396 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Doing Democracy

Activist Art and Cultural Politics

About this book

Doing Democracy examines the potential of the arts and popular culture to extend and deepen the experience of democracy. Its contributors address the use of photography, cartooning, memorials, monuments, poetry, literature, music, theater, festivals, and parades to open political spaces, awaken critical consciousness, engage marginalized groups in political activism, and create new, more democratic societies. This volume demonstrates how ordinary people use the creative and visionary capacity of the arts and popular culture to shape alternative futures. It is unique in its insistence that democratic theorists and activists should acknowledge and employ affective as well as rational faculties in the ongoing struggle for democracy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Doing Democracy by Nancy S. Love, Mark Mattern, Nancy S. Love,Mark Mattern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Kunst & Kunst & Politik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Introduction

Chapter 1

Introduction

Art, Culture, Democracy

Along with the political speeches and the oath of office, the historic inauguration of Barack Obama as the first African American president of the United States featured music, poetry, and prayer. We believe that this signaled a propitious moment to inquire whether these alternative and aesthetic modes of public discourse prefigure a more democratic future. In various ways, contributors to this volume ask: What arts and cultural forms present in the world today provide grounds for optimism about moving toward a more democratic society? What is the promise of the arts and popular culture as partial bases for political activism to move us toward a new political economy and a more democratic politics? How does this promise engage with existing economic and political realities? In what concrete ways are contemporary arts and popular culture forms used to increase the capacities of individuals and groups to act effectively in the world? In particular, how do historically marginalized groups employ the arts and popular culture to advance their political claims and exemplify democratic practices? In sum, how might the arts and popular culture help us do democracy?

These questions arise in a context of rapidly expanding global communications networks. Access to the arts and popular culture has increased commensurately with access to smart phones and the internet experienced across the globe. Musicians, photographers, graffiti artists, painters, dancers, performance artists, filmmakers, writers, and many others now take advantage of internet platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube to disseminate their work. Many do so with explicit political intent. One result is a rapidly changing and expanding terrain for political thought and action using arts and culture. The internet has blurred borders between local and global communities as well as traditional and modern cultures. However, the result has not been a world without borders. The digital divide between rich and poor, north and south, persists. Internet technology has also supported the creation of new borders, such as virtual diasporic communities, global hybrid movements, and even internet-based cybernations.1

Another important element of this changing context is the rise of so-called culture wars that link the traditional politics of nation-states with globalization and multiculturalism. At stake is control of the hearts and minds of citizens around the world. Various forms of expression, including and especially those related to the arts and popular culture, carry profound significance for this challenge of engaging reflectively and critically with diverse citizens. While much of popular culture undermines the development of critical consciousness and globalization often homogenizes or even Americanizes, the arts and popular culture also have been used extensively and successfully to nurture critical consciousness and diverse perspectives. The central questions remain: To what degree will political and economic elites continue to fashion the world, both materially and symbolically, in their own interests, and to what degree can activists harness the arts and popular culture to shatter this hegemony and challenge elite power? Although most contributors here focus on how activist art supports progressive causes, some consider how the arts and popular culture are used to resist democratic change and restore traditional hierarchies of class, gender, and race, though perhaps in new forms. These different emphases work together to show how the creation of a democratic society is an ongoing process and that democracy can also unfortunately be undone by some of the popular forces often thought to foster it.

The Arts and Popular Culture

What do we mean by the arts and popular culture? Many have found it tempting to define a separation between so-called high art and low art.2 Art hanging on museum walls and performed in magnificent concert halls is deemed high art, while art sprayed-painted on railroad underpasses and performed in anarchists' squat houses qualifies as low art or, presumably, popular culture. We intend to avoid this temptation, because it is ultimately an untenable distinction. Institutional definitions such as these focus on artworks as beautiful objects created for an art world, especially art critics. The effect of this approach is to perpetuate established artistic traditions, including the concept of autonomous art, and to exclude innovative and nonwestern art forms.3 According to Marshall McLuhan, new art forms are routinely regarded as corrupting or degrading the standards of high art. However, these new art forms often simultaneously serve to legitimate the elevated status of the “great” artworks that preceded them and many new forms are eventually granted the status of high art.4 At the very least, these interrelationships suggest that historical context shapes our definitions of what constitutes high and low art. However, more than historical context is at stake here. The arts associated with popular culture are also often dismissed as mere entertainment, as commercialized art produced for mass markets.5 Yet the arts and popular culture also serve a variety of important functions in everyday life. These functions involve more than the artistic beauty that is often found in the ordinary objects that enhance our daily lives. They also include the role of the arts in catalyzing the imagination, expressing creativity, integrating aspects of the self, providing meaningful symbols, sustaining a sense of beauty and harmony, and, most important here, resisting conformity and even subverting the status quo.6 In these ways, especially the last one, the popular quality of the art forms included here potentially increases their importance for democratic and undemocratic politics.

Although all of our contributors demonstrate the significance of the arts and popular culture for “doing democracy,” they differ in their approaches to defining and analyzing the art forms they discuss. For this reason, we have chosen not to focus on the aforementioned debates over how to define art in general, or even on how to define the individual art forms included in this volume.7 We would instead emphasize the aesthetic experience of the arts and popular culture, a theme the authors here share. The term “aesthetics” comes from the Greek aesthesis, and refers to “the whole region of human perception and sensation” or “the whole of our sensate life together.”8 Aesthetic experience extends beyond the arts proper to include everyday life, the natural world, and the spiritual realm. Although aesthetic experience is conceptually distinct from artistic experience, it is often closely related in practice. John Dewey, who laments the lack of a single term that unites artistic and aesthetic experience, famously joins them. He writes: “the conception of conscious experience as a perceived relation between doing and undergoing enables us to understand the connection that art as production and [aesthetic] perception and appreciation as enjoyment sustain to each other.”9 Dewey's concept of aesthetic experience expands our experience of “the arts.” It can recognize innovations in content, form, or both as “art”; it also includes the artistic expressions of popular and nonwestern cultures. For Dewey, the arts and popular culture draw on non- and extra-rational dimensions of human identity and experience, while also potentially stimulating critical reflection and shaping political interactions. Like the arts and popular culture, these affective and corporeal dimensions of human experience, which some claim may even constitute an alternative and aesthetic rationality, have arguably received too little attention.10

The distinction between high art and popular culture overlaps with another distinction between formal (or technical) and performative aesthetics.11 A formal aesthetic focuses primarily on the abstract systems, structures, and techniques of artworks. For example, a formal analysis of a classical music composition would emphasize its harmonic development, melodic lines, and rhythmic meter. Abstract forms can and sometimes do provide models and metaphors for sociopolitical arrangements. The musical counterpoint of a fugue may mirror the distinct voices in a political dialogue; likewise, perspective lines in an artist's portrait may reveal complex social hierarchies.12 As we have seen, more popular art forms often fail to qualify as “art” when measured by the standards of formal aesthetics. We would expand the notion of artistic form beyond the requirements of high art to a variety of popular forms including, for example, military monuments, political cartoons, popular festivals, and public parades. Contributors to this volume also offer more dynamic and democratic understandings of what have traditionally been regarded as forms of high art, including literature, music, poetry, and theater. The capacity of musical form—classical and popular—to “speak” without words plays a role in multiple chapters. Digital forms that incorporate multiple earlier media—television, radio, and newspaper—also increase the power of art for politics. In these and many other cases, to use Marshall McLuhan's famous phrase, “the medium is the message,” and the various art forms can carry democratic or undemocratic content.13

A performative aesthetic better incorporates this more dynamic and inclusive concept of aesthetic form(s). It also places greater emphasis on the affective, corporeal effects of art, especially its capacity to shape the identities and express the needs of groups excluded and marginalized by mainstream politics. Rap music, for example, involves much more than a musical style. It is part of a wider hip hop scene that includes break dancing, dee-jaying, and remixing, as well as “authentic” dress, paraphernalia, fanzines, and websites, all part of the larger Do-It-Yourself (DIY) movement.14 Most important, a performative aesthetic construes audiences as participants in artistic experiences and stresses the artist's engagement with a wider community. Unlike formal aesthetics that elevate art, in part, by making it an object of detached observation in designated spaces, a performative aesthetic explores how people enter into artistic experiences. In doing so, it challenges the assumption that art is somehow autonomous and embraces its role in processes of socioeconomic and political change. Although the arts and popular culture carry and convey content in written form, such as cartoon captions, song lyrics, and theater scripts, they often seek to erode the very distinction between form and content. Many contributors here show how the arts and popular culture ultimately present “form as content” by modeling new ways of doing and sometimes undoing democracy.15

This understanding of the arts and popular culture as integral to political and, more specifically, democratic processes calls into question the liberal-democratic idea that society has distinct public and private spheres, and that art belongs in the latter realm of personal experience. According to John Locke, liberal individuals demonstrate their capacity to bear the full rights and responsibilities of citizenship through their rationality, industry, and property.16 For the rational citizens of a liberal democracy, aesthetic sensibilities are largely private matters of personal taste and individual choice. The liberal state tolerates differences in artistic preferences, as well as a variety of political views and religious beliefs, as long as those differences do not violate the rights of other citizens.17 Of course, one way a rising middle class can display its excellent and quasi-aristocratic taste is by enjoying and acquiring critically acclaimed or high art and emphasizing high art's superiority over all lower art forms. Wider access to high art through concerts, museums, and theaters open to the public only became possible in Europe very gradually over a period of several centuries. The liberal tendency to locate the arts in the private sphere contributed to perceptions of the artist as an individual, even solitary, creative genius, rather than part of a community. This also reinforced the concept of art as autonomous, as somehow transcending the pressures of economic and political reality.18 Locating art in the private sphere also served to reinforce the “rationality” of liberal democratic politics. The affective, corporeal experiences associated with the arts became personal matters that were most appropriately confined to the inner worlds of liberal subjects.19 Members of marginalized groups, such as women and children, laborers, and other races, were also thought to be more vulnerable to these less-than-rational forms of experience. This greater vulnerability served to further justify their exclusion from full political rights.20 Although some aesthetic sensibilities, like imagination and sympathy, remained important factors that informed the political judgment of liberal subjects, these qualities needed to be carefully cultivated and controlled. An aesthetic concept of the sublime might indirectly guide political judgments, but it was not an adequate or appropriate foundation for political institutions and processes.21 From this larger perspective, the liberal privatizing of the aesthetic can itself be seen as a cultural-political project with significant implications for how citizens understand and practice democracy.22

There is no question that aesthetic experiences often prompt visceral responses that can prove dangerous to political orders, including purportedly democratic ones.23 The arts and popular culture are often romanticized as sites of popular resistance, as inherently democratic terrains of struggle against hopeless odds, as authentic expressions of the people, and as naturally effective counterweights to power exercised in the interests of domination. Aesthetic experience sometimes does counter hegemonic powers, and the popular expressions of the arts considered here serve a variety of functions for progressive social movements. These include: “survival/identity, resistance/opposition, consciousness-raising/education, agitation/mobilization.”24 Yet a balanced look at the arts and popular culture will quickly reveal that they are also sites of domination and oppression where citizens are misled and their interests distorted; where various undemocratic ends are pursued, often successfully; where the possibility of resistance is systematically erased; and where the notion of authenticity is hopelessly obfuscated. Antonio Gramsci uses the term “hegemony” to describe how a ruling class can establish political control by shaping the dominant cultural institutions of civil society. For Gramsci, cultural projects are a primary field of political struggle, a site where counterhegemonic artists and intellectuals can also prefigure a new society and join with others to create it.25 The liberal depoliticization of the aesthetic p...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgments

- Part I. Introduction

- Part II. Photography and Cartoons

- Part III. Monuments and Memorials

- Part IV. Literature and Poetry

- Part V. Music

- Part VI. Theater

- Part VII. Festival and Spectacle

- Part VIII. Conclusion

- Contributors