![]()

Part I

Hasidism and Renewal

![]()

1

The Place of Piety

Piaseczno in the Landscape of Polish Hasidism

MARCIN WODZIŃSKI

Academic studies of Hasidism too often focus on the life, ideas, and doctrines of great personalities and assume a kind of natural correspondence between the intellectual achievements of Hasidic leaders (tsaddikim) and their social impact. This error is not unique to Jewish and Hasidic studies but may be exacerbated by the continuing influence of traditional yeshiva-style scholarship on academic research. At the same time, the rapid development of academic Jewish studies and its embrace of modern methodologies recapitulated the fascination with a privileged corpus of texts and their mostly elite male interpreters, at the expense of other concerns. The problem is especially egregious in Hasidic studies, which has not until recently paid much attention to the hundreds and thousands of rank-and-file Hasidic followers, focusing instead on the life and, especially, the ideas of the tsaddikim. Historians have all too often tended to forget about the vast majority of Hasidim, who lived outside of the Hasidic courts in countless townlets of eastern and east-central Europe.

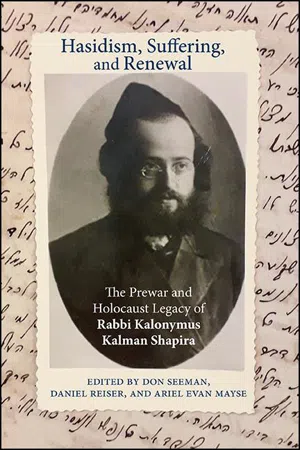

The case of the Piaseczner Rebbe, R. Kalonymus Kalman Shapira of Piaseczno, is no different in this regard. While there has been impressive progress in the study of the doctrine and teaching of the Piaseczner Rebbe, this very volume being the most impressive proof of this development, there has been no comparable progress in research on his social context and significance during his own lifetime. We know surprisingly little about the scale of this tsaddik’s social influence or the demographic characteristics and geographical distribution of his followers. How many followers did he have? Where did they live? What was their socioeconomic profile? How was the Hasidism of Piaseczno positioned with respect to other contemporary Hasidic or non-Hasidic groups? To what degree was Piaseczno representative—or atypical—of interwar Hasidism in Poland?

In this introductory essay, I have neither the intention nor the ability to respond to all of these major questions. Instead, I will focus on outlining the essential contextual characteristics of the Hasidic presence in Piaseczno and how it might have influenced R. Shapira’s activities, or, to put it another way, the extent to which R. Shapira’s activities can be understood as representative of wider trends characterizing the Jewish community of interwar Poland. We will need to understand something about the size and influence of Piaseczno Hasidism (i.e., the followers of the Piaseczner Rebbe) and what these features can tell us about the rebbe and his teaching. My observations will of necessity be somewhat preliminary, as we are only at the beginning of this type of research into Piaseczno and other Hasidic groups.

Hasidism in Piaseczno

The town of Piaseczno was established in the thirteenth century as a rural settlement. It received municipal charter in 1429 and started to develop as a minor commercial center. The process was relatively slow, as Piaseczno was, like many such settlements, repeatedly destroyed by wars and fires, including the Polish-Swedish war of the mid-seventeenth century and then the series of wars and uprisings that took place at the end of the eighteenth century. At that time, about five hundred people lived in the town.

It was only at the end of the eighteenth century that Jews appeared in Piaseczno, since the town had previously enjoyed the right to exclude Jewish residents. Of a population of 565 people in 1808, only 26 (5 percent) were Jews. In the years following, the proportion of Jews in the town grew rapidly, reaching 515 people, or 42 percent of the total population, in 1857. At that time, Piaseczno was not treated as an independent Jewish community but only as a filial branch of the kahal in nearby Nadarzyn. Despite its constant efforts to gain communal independence, the Jewish community of Piaseczno maintained its status as the filial extension of Nadarzyn until the end of the nineteenth century.

By the middle of the nineteenth century, Hasidim had become an increasingly visible segment of the Jewish community and influenced the flavor of religious life in the town. When the Polish government introduced a ban on “Jewish attire” in the 1840s, the Hasidim in Piaseczno expressed strong opposition to the new law. Piaseczno had the third-highest number of people seeking legal exemptions to the ban in the whole province of Mazovia; it was surpassed only by the Hasidic strongholds of Amshinov (Mszczonów) and Vorke (Warka). This is an indirect but suggestive indication of the relative strength of the town’s traditionalist community, including Hasidim. In addition, the ten kvitlekh (petitionary notes) delivered by Piaseczno Jews to rabbi and semi-tsaddik R. Eliyahu Guttmacher of Graydits (Grodzisk Wielkopolski; 1795–1874) indicate a relatively high interest in Hasidic forms of religious life in Piaseczno. Likewise, Jewish ethnological materials collected in Piaseczno at the beginning of the twentieth century testify to rich Hasidic traditions and bear witness to the strong cultural influence of popular Hasidic folk culture in the town.

The growth of Hasidism was not, of course, uncontested. One non-Hasidic Jew complained that “in the good old times, Jews would gather in the synagogue for Rosh Hashanah (the Jewish New Year) early in the day and stay there until the afternoon. Now, on such holy days, the Hasidim smoke their pipes till eight or nine in the morning, and when they finally arrive [at the synagogue], they are done with their prayers in an hour.” A report by missionaries from the London Society for Promoting Christianity amongst the Jews, which was active in Poland, reported on significant conflicts over the rise of Hasidism in the town:

In the town here, there exist two parties, the Hasidim and the so-called mitnagdim, that is, the opponents of the former, and they continually argue with each other. The former group has its own rabbi, and they want him to be recognized in his office by the rest of the Jews. Others brought a different rabbi, closer to their way of thinking, and they demanded that he be recognized as the town rabbi, while they persecute the other one. The anger between these two sides supposedly reached such a level of hostility that … the supporters of both parties had a regular fistfight in the synagogue on Rosh Hashanah, for when one party demanded that their rabbi deliver a sermon, the others shouted that their rabbi should do it instead.

This picture is fairly typical for a town in which, having already gained at least relative institutional and financial autonomy, the Hasidim sought to increase their social power by exercising decision-making authority over communal institutions.

It is true that Hasidim had been appointed to rabbinical positions since the earliest stages of the movement, but in earlier periods these appointments were more frequently made on the basis of other criteria, such as Talmudic knowledge, ties with influential families in a town, or willingness to accept a position in a small town with little remuneration. Appointments to the rabbinate became a subject of political controversy only when local Hasidic communities proposed their own candidates despite doubts regarding those candidates’ suitability for the post, or when they opposed the non-Hasidic candidate only because of his views on Hasidism. This only happened in situations in which the Hasidic group felt strong enough to impose its views despite the lack of community consensus, which was apparently the case in Piaseczno by the middle of the nineteenth century.

Hasidim had many reasons for showing interest in the appointment of communal rabbis, including, of course, the opportunity to spread Hasidic values and thereby influence community norms. A second reason was financial: rabbis received a salary from the communal budget, and even if this remuneration was modest, it would typically be supplemented by extra income for performing religious ceremonies. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many tsaddikim found that their income from donations by their immediate followers was insufficient, so they had to seek other sources of income. Several Hasidic leaders, such as R. Henokh Lewin of Aleksandrów (Alexander), became rabbis only in the wake of bankruptcy following a business failure. Financial need, decreasing numbers of followers due to secularization, and a sense of institutional crisis may all have been reasons that someone like R. Kalonymus Shapira would seek recognition as a communal rabbi during the first half of the twentieth century.

Tsaddikim in and of Piaseczno

Despite the significant development of its Hasidic community, nineteenth-century Piaseczno remained only a provincial center of the Hasidic movement. The strongest local group consisted of followers of the tsaddik of Grodzisk (father of the Piaseczner Rebbe), but despite significant local influence, the town’s Hasidic community never had the importance of those of neighboring towns such as Ger (Góra Kalwaria) and Amshinov (Mszczonów). It was only with the appearance of charismatic Hasidic leaders in the early twentieth century that this situation began to change.

It seems that the first Hasidic leader to settle in Piaseczno was R. Israel Yitzhak Kalisz, son of the tsaddik Simhah Bunim Kalisz of Otwock (Warka-Otwock dynasty). R. Kalisz came to Piaseczno around 1907 and became a local tsaddik there, combining this function with serving as tsaddik in Otwock. This was, however, only a short-lived leadership, as R. Kalisz does not seem to have spent World War I in Piaseczno, and he died in a typhus epidemic at the age of thirty-six, soon after the war.

Another member of a prominent Polish Hasidic dynasty, R. Meir Israel Rabinowicz of the Przysucha dynasty, son of the tsaddik of Szydłowiec, Tsemah Rabinowicz, arrived in Piaseczno around 1909. After marrying a daughter of prominent Ger Hasid and communal Rabbi of Piaseczno Noah Sekewnik (1893–1913), R. Meir Israel also soon began to act as a tsaddik. While not much is known about his particular activities, we can assume that he acted like all other tsaddikim, leading a small group of followers, providing spiritual guidance, arranging festive gatherings, accepting petitions with requests for help, and so on. He continued in this vein until his death, in 1926, after which the dynasty was continued by his son, R. Ya’akov Rabinowicz. This brief dynasty was extinguished when R. Ya’akov was murdered, along with his whole family, during the Holocaust.

This is the crowded field in which R. Kalonymus Kalman Shapira (1889–1943) emerged as one of three tsaddikim simultaneously active in Piaseczno. He was the son of tsaddik Elimelekh Shapira of Grodzisk, an offshoot of the Mogielnica-Kozienice dynasty. R. Shapira began his activities as a tsaddik in 1909 and became communal rabbi in 1913, after the death of the previous occupant of the position, R. Noah Sekewnik. This may not have been a very prestigious position. Yekhiel Yeshaia Trunk writes that Piaseczno replaced Chełm in Polish-Jewish folklore as the embodiment of batlonut, or idleness. The previous rabbi had even been made a popular laughingstock as the new incarnation of the well-known joke about the fool...