![]()

Chapter 1

Agency of Ornaments

Identity, Protection, and Auspiciousness

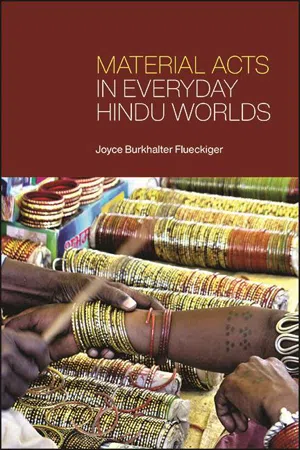

When I return to India, I normally replace the Chhattisgarhi silver bangles that I wear in the US with glass bangles. But several years ago, on a trip to Chhattisgarh that was to last only a few days, I hadn’t taken off the silver bangles. Although I knew that among my lower-caste and lower-class friends in Chhattisgarh, to wear silver only was not appropriate for a married woman, I thought that for this short trip when I wasn’t going to be conducting formal fieldwork, my silver would pass. However, I learned otherwise. I met a long-time Gond (adivasi, tribal) friend, Rupi Bai, in the town of Dhamtari for a very quick visit. After serving me tea and some preliminary conversation about how my children were, she began to finger my silver bangles, up and down my forearm, and then said in a resigned tone, “This isn’t good [yeh to accha nahin hai].” I knew immediately what she was referring to and stumbled around for a response. But she had a plan: “Let’s go to the temple and buy you some glass bangles [churis].” And soon my arm was graced with twelve auspicious red glass bangles, with bits of gold-color paint daubed in the cut indentations on each bangle (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Bangle seller breaking a woman’s old bangles and replacing with new ones, Chhattisgarh. Note ornamentation of Gond tattoos on the woman’s forearm. Photo by the author.

My bangle advisor, Rupi Bai, had been widowed for about fifteen years, at which time, according to custom, a female relative had broken Rupi Bai’s glass bangles. While, according to Gond custom, she would have been permitted to still wear silver ornaments, she had not owned silver before becoming a widow, so for many years her arms had remained empty except a single bent-aluminum bangle. In most Indian communities, glass bangles are appropriate only for unmarried girls (optional) or married women (traditionally required). In lower-caste Chhattisgarhi communities, glass bangles, rather than a wedding pendant (tali or mangalsutra), are the primary ornament of marriage. Among castes that permit divorced women or widows to get married again, the second wedding ritual is called “putting on churis” (churi pahinana, lit., to cause churis to be put on). As one of my elder friends asserted when showing me and naming her various ornaments, “Only a churi-walli [one who wears glass bangles] can wear all the other ornaments; the bangles are first.”

Rupi Bai’s intervention to replace my silver bangles with glass suggested that wearing silver only, without interspersed glass bangles—a sign of widowhood—may bring misfortune to my own married state. The silver bangles had their own agency, despite my human intentions. On this visit Rupi Bai was wearing white plastic bangles (the first time I had seen these), which suggested that it is not only ornamentation that helps to create a woman’s auspiciousness: the physical substance of the glass of those bangles has its own agency. Glass is both fragile (much as marriage itself) and tinkles, alerting the presence of an auspicious woman, whereas plastic is relatively permanent (like widowhood in this community, in which remarriage is rare) and gives no sound. However, Rupi Bai continued to wear other auspicious ornaments: tattoos. She is part of a Gond community among which there is a common saying, referring to tattoos: “A Gond woman will never die without her ornaments.” The saying became particularly poignant to me after Rupi Bai became a widow; even though her glass bangles had been broken, her tattoos remained.

While the materials and designs of ornaments vary widely in different regions in India, there is a shared assumption across regions that ornaments are not just decorative; they do something: they protect; they make whole; they create auspiciousness; they signal and help to create regional, caste, and class identities; they reflect and create relationships. To be ornamented is to be complete, fully human. “A person or thing apart from its appropriate ornaments,” art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy asserts, “is valid as an idea, but not a species” (1938, 252; cited in Waghorne 1994, 258). The term alankara literally means to make adequate, to make present, to strengthen. In India bare arms and necks, without some form of ornamentation, be it a simple thread or silver, gold, or glass ornaments—for babies, girls, and women, in particular—are inauspicious, incomplete, vulnerable, and invite the evil eye. As art historian Vidya Dehejia observes, “To be without ornament is to provoke the forces of inauspiciousness, to expose oneself to danger, even to court danger” (2009, 24).

While all ornaments are on some level protective, some are more consciously thought of as such than others, and some bodies need more protection in certain contexts than do others. Ornamental protection begins at birth. Babies are particularly vulnerable to the evil eye (nazar; drishti) of relatives, neighbors, and strangers who may look upon the baby wishing for one of their own, of others who may be envious of the good health and beauty of a baby, or even of the inadvertent evil eye drawn by well-wishers’ positive comments about a baby. (To avoid the latter, traditionally it is culturally inappropriate in India to comment on a baby’s beauty or cuteness.) And so many babies are protected with dots of kohl on the side of their forehead and at the bottom of their little feet and a simple protective string (which may hold an amulet) around their necks or waists. Some babies wear plain black glass bangles or little black bangles studded with pieces of reflective glass that are believed to literally deflect the evil eye.

Ornaments of Marriage

Ornaments become particularly important for women upon marriage. As girls they may wear threads around their necks, glass bangles, and perhaps small earrings (or often in villages, a small bamboo stick in their pierced ears), but when they get married, glass bangles and silver or gold ornaments of particular (regional and caste-associated) designs mark and help to make their new status as married women. We get a clue about the agency of ornaments through a Telugu ritual called pelli kuturuni cheyyadam (lit., making a bride). The bride is “made” in a ritual gifting of glass bangles by other married women, who individually put the bangles on the bride’s wrist. “Modern,” educated women often do not keep wearing these glass bangles on a daily basis, preferring one or two gold bangles, but for this Telugu ritual glass bangles are still essential. In some Chhattisgarhi communities, a similar ritual makes a bride when married women (most of whom attend this ritual highly adorned) take a small bit of sindur (vermilion) powder from the parts of their hair (only married women wear this sindur) and apply it to the part of the bride. When all the married women have done so, the groom appears briefly in the women-only ritual to apply the final pinch of sindur to his bride’s part; now she is fully “made.” In both rituals, the assumption is that the materiality of glass bangles and sindur is not only reflective of an intended marital status but also that such ornamentation has agency to both transform and thereafter maintain the marital status of a woman. Similarly, at a very different life stage, the poignant removal of auspicious ornaments (sindur, bangles, wedding pendant, and toe rings) make a woman a widow. Significantly, this ritual, as described to me by a Telugu Brahmin friend whose sister had just become a widow, does not occur in their families until the tenth day after the husband’s death. The woman without a living husband is not fully a widow until she takes off the ornaments that have earlier made her a bride.

A common term for ornamentation, shringar, means adornment and can also have connotations of erotic love (being one of the nine rasas, or aesthetic emotions.) This would be one reason it is not appropriate for widows to wear auspicious ornaments such as glass bangles, since traditionally widows would be exempt from participating in (or suggesting) eroticism. For brides and queens, the traditional number of ornaments is sixteen (Hindi, solah shringar)—from hair ornaments, earrings, armbands, necklaces, waist belt, ankle bracelets, to toe rings. (The specific ornaments may vary from region to region.) Shringar ornamentation is not limited to jewelry; it can also include (in the listing of sixteen) clothing, fragrance, hair styling, and henna (Dehejia 2009, 34–36). Many Sanskrit and vernacular-language literary texts, as well as folk songs, describe human or divine bodies as adorned from head to toe (sikha nakha) or toe to head (nakha sikha) (figure 1.2). Ideally, every part of an auspicious woman’s body is adorned—thereby protected—although, of course, many (even most) brides’ families cannot afford to adorn their daughters in full solah shringar.

Figure 1.2. Ornamented elder, Hyderabad. Photo by the author.

In most regions of India, married women wear some form of wedding chain or string around their necks. In many parts of North and Central India, the chain—mangalsutra (lit., thread of auspiciousness)—is composed of gold and black beads that may or may not hold a gold pendant; in Chhattisgarh, the mangalsutra of mid-level and upper castes is a row of gold leaf-shaped pendants hanging on a black thread. In South India, married women wear a gold tali either on a turmeric-rubbed string, or, if affordable, the thread may be replaced by a more durable gold chain after the wedding rituals. In the South, women say they should never take off their talis, even while bathing and sleeping, suggesting that even a few hours without the tali may threaten a woman’s marital status and auspiciousness; whereas in the North, many women either come from castes that do not wear mangalsutras or do not wear them on a daily basis. (Folklorist Pravina Shukla suggests that the equivalent “must-wear” sign of marriage in Benaras is sindur [2008, 372–75].) While many women may buy and sell their gold ornaments for needed cash flow, or may have them remade in new designs to keep up with fashion, a living woman’s tali is never sold or exchanged. Shukla observes that jewelers know this fact about talis and mangalsutras, so, ironically, the chance that the gold of these ornaments may be tainted is better than that of other ornaments, since the wedding pendant/chain “will never be sold and therefore never tested” (2008, 179).

The mangalsutra or tali is not worn for show or evaluation, in contrast to many other ornaments that are worn to be seen and may be evaluated for aesthetics, taste, style, monetary value, and so on. Traditionally, the South Indian tali should not be visible but should remain tucked inside a woman’s clothing, hanging between her breasts. (On occasion when my own tali has fallen outside my sari blouse or kurta, South Indian friends have often discreetly tucked it back in beneath my clothing.) The “work” of a tali is not visual. The pendant itself is not primarily a display of wealth, although one may deduce the economic class of its wearer, depending on whether a woman is wearing her tali on a turmeric thread or gold chain and by the thickness of such chain, which can be seen around the back of the neck. Nor are the designs of talis personal or aesthetic choices; a woman wears the traditional tali design of her husband’s family, caste (jati, kulam), and region.

With arranged marriages, of course, the bride’s and husband’s castes are traditionally the same. However, in cross-caste marriages (which remain a very small minority), the tali design is generally that of the husband’s family. When one of my Indian American Tamil graduate students married a Gujarati American man, the tali design was a topic of negotiation—although that there would be a tali was assumed. The compromise was that her husband tied a Gujarati-designed mangalsutra around her neck during the wedding ritual, and she chooses to wear daily a small version of the Tamil tali design of her own family. This tali had originally been made to offer to a small image of a goddess, hence its tiny size; it was more convenient, my student said, to wear with non-Indian clothes on a daily basis. While the design and materials of talis, mangalsutras, and other ornaments perform regional and caste identities and, as such, are of particular interest to the anthropologist, most women are not reflexive about this aspect of the agency of their ornaments.

I saw many of my friends’ talis for the first time only when I asked them to pull them out from beneath their saris so that I could photograph them. In the courtyard of a goddess temple in Tirupati, I learned that talis are either too powerful or too vulnerable (it wasn’t clear which) for two women to show me theirs at the same time; taking turns, the flower sellers pulled out (from under their saris) their talis, one by one. While the women couldn’t further explain the prohibition of two talis not being visible at the same time, they thought I might be right about my conjecture that the reason for the prohibition was the power (shakti) of the talis. Through their talis, I also learned the castes and regional identities of women, which was sometimes a surprise. For example, seeing the shape of her tali, I found out that the husband of one of my Tirupati friends was Tamil rather than Telugu, which I had always assumed. She explained that although her husband had been born in and had lived in Tirupati all of his life, his family still identified as Tamil and gave Tamil-designed talis to their daughters-in-law. The sectarian affiliation of some Brahmin women became apparent when I saw their tali designs—whether they were from a Shri Vaishnava Iyengar family (the tali designed with Vishnu’s namam) or a Shaiva Iyer family (the tali marked with a Shiva linga).

On the occasion of the wedding of a Kannada Brahmin graduate student from Emory University, I learned that in many families, a bride is given two talis: one from her mother and one from her husband. I observed a pre-wedding ritual during which the student’s mother tied a tali, hanging on a turmeric thread, around the neck of a ritual pot (a form of the goddess Lakshmi). At the end of the ritual, she tied the same tali around her daughter’s neck—before the wedding. In this family it was the custom for the bride to wear this maternal tali for fourteen or twenty-one days after the wedding, on a separate string from that of the tali tied by the husband during the wedding ritual itself. Many women thereafter wear the two talis tog...