![]()

CHAPTER ONE

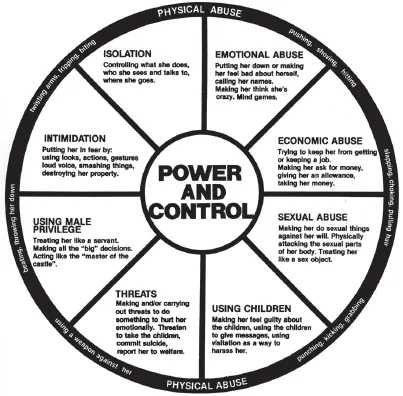

The Power and Control Wheel

From Critical Pedagogy to Homogenizing Model

In this chapter, I examine the social history of one of the most important tools used by the movement to stop violence against women. The tool, or model, is called the “Power and Control Wheel.” Activists and advocates at the Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project (hereafter the Duluth Project) devised the Power and Control Wheel as a tool for participatory education, but it was altered as it became popular throughout the United States and became institutionalized in many antidomestic violence programs.

From the beginning of the second wave of feminism in the early 1970s, feminist activists made the connection between violent relationships and the institutions that supported violence against women. Ellen Pence, a well-known activist associated with the Duluth Project, describes the unwillingness to yield a social and political analysis of violence against women.

The battered women's movement has, since its earliest days, identified battering not as an individual woman's problem, but as a societal problem linked to the oppression of all women in our society. Institutions in our communities were engaged in practices that blamed women for being beaten. Early organizers in the movement challenged mental health centers who claimed women were sick, police who charged that women were provocative, courts that refused to acknowledge that women's bruises were the result of criminal behavior … and an economic system and a community … over and over again reinforced a batterer's power over women. (Pence et al. 1987, 5)

The political project of Pence and others was to raise critical understanding among battered women of how institutional, structural, economic, and cultural forces are implicated in violence against women. The activists who invented the Wheel were trying to link private and public violence.

FIGURE 1. Power and Control Wheel.

At some point, however, part of their work became co-opted by oppressive economic and organizational forces. As one counselor in New York told me in an interview, “We follow the ‘Duluth Model’ of Ellen Pence. If you want funding in New York, you must use that model.” As it became institutionalized around the country, it was used in a way that masked the link between public and private violence. It was also used in a way that made diversity in the experiences of gendered violence harder to see. Success in one set of terms—public recognition, increased funding—has resulted in a failure to sustain its more ambitious political critiques. Though originally open to a diversity of understandings of violence, including the collusion of a range of social and cultural forces in violence towards women, it now seems generally to be used to provide a template to describe violence against women as if it followed a single pattern. Pence, one of its authors, seems to have congealed in her views. “The ones that are on there I think are core tactics that almost all abusers use” (quoted by Pheifer 2010).

The story of the Power and Control Wheel shows how grass-roots, democratic research can be used to analyze and fight against oppressive forces, in this case against a largely invisible and diffuse war against women. The other side of the story, however, is that one must be vigilant to insure that politically liberating practices remain so.1

The perils of institutionalization are not lost on the founders. In a training manual to combat domestic violence, Ellen Pence and Bonnie Mann express an unwillingness to surrender a collective and collectively renewed political, social, and cultural analysis of the circumstances of battered women. “Over the past ten years the nature of women's groups offered by shelters and battered women's programs has evolved from a cultural and social analysis of violence to a much more personal psychological approach. Our own experience fits this pattern” (1987, 47). How did their work move from social analysis to psychologizing individual women?

In the introduction to this work, I argued for the need to dismantle the fiction that women's experiences of violence are uniform. As one looks at institutional response to violence against women, one sees that these institutions tend not to see—in fact tend to erase the differences. In particular, the social, cultural, and structural forms of violence are often the most elusive. In this chapter I describe one place the differences are erased: in some strands of the movement to end violence against women. In a later chapter, I take up the role of the courts in this process.

One cannot presume to measure for all time the efficacy of a particular tactic or strategy independent of how it is practiced, by whom, and with what sort of institutional backing. Apparent confinement can be refuge. What looks like refuge is sometimes confinement. What something means, what it stands for, and how it is used changes through time and context. Stuart Hall:

The meaning of a cultural form and its place or position in the cultural field is not inscribed inside its form. Nor is its position fixed once and forever. This year's radical symbol or slogan will be neutralized into next year's fashion; the year after, it will become the object of a profound cultural nostalgia … The meaning of the cultural symbol is given in part by the social field into which it is incorporated, the practices with which it articulates and is made to resonate. What matters is not the intrinsic or historically fixed objects of culture, but the state of play in cultural relations. (Hall cited in Giroux 1992, 187)

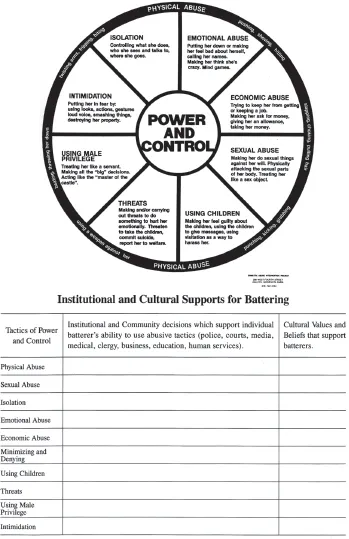

POWER AND CONTROL WHEEL: METHODOLOGY AND CRITICAL PEDAGOGY

To get a handle on some of the complexity of liberation and collaboration, radical action and conformism, the new and the old, I will first interrogate the critical pedagogy of the Power and Control Wheel. As the staff of the Duluth Project first conceived it, the Wheel has two parts (figure 2) (Pence et al. 1987, 31ff). I have seen the first part of the Power and Control Wheel in practically every program I have been to or heard about, including several versions in Spanish. It has been translated into forty languages worldwide, including Maori, Hungarian, and Icelandic. But generally speaking, the entire two-tiered approach, used as an educational tool, has been absent. The second part of the code, that part that seeks to uncover and describe institutional and cultural collaboration with the batterer, is often eliminated.

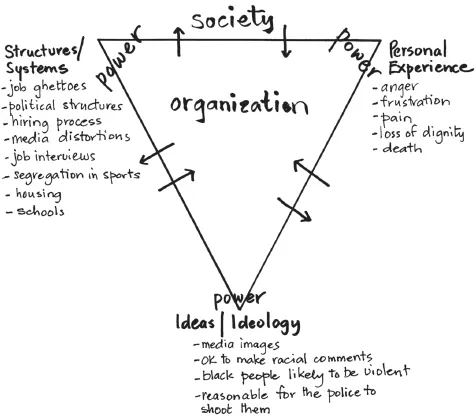

FIGURE 2. Institutional and Cultural Supports for Battering.

The Wheel was developed from a specific methodology that drew heavily from the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire.2 His contribution is a pedagogical theory to develop a “critical consciousness.” A critical consciousness of domestic violence, for example, would be one in which a battered woman can situate individual abuse within greater societal processes of oppression and domination. The Power and Control Wheel works as a pedagogical tool for the analysis of violence, an analysis that then passes into wider consideration of institutional and cultural supports for battering.

In reviewing the code and method, I will pay special attention to how it instigates a critical appraisal of domination. That is, I would like to look at its methodology for uncovering violence.

BACKGROUND AND HISTORY

The Duluth Domestic Abuse Intervention Project was begun in the late 1970s by a group of battered and formerly battered women, each of whom had survived battering in the absence of a formal shelter or hotline. They formed a women's group to begin to discuss and develop responses to the violence each had experienced. They also began an educational campaign to provide information to the community on violence against women. As they flourished as an organization, they perceived a need to develop new educational methods. “The neighborhood-based education groups were well attended and very successful. However, after several years, we felt increasing discomfort with the process we were using. Our lecture/discussion format provided information but did not truly involve women in the process of discovery. There was an imbalance of power in our ‘giving’ women information and their receiving it. We began to experiment with Freire's teaching methods” (Pence et al. 1987, 1–2). It was through Freire's methods that they moved away from simply providing information. The methodology as they practice it begins with surveys and interviews with battered or formerly battered women. “Each year since 1981 we have conducted a survey of women, asking what kinds of issues they want to discuss in groups. These surveys are crucial to the educational process. No matter how many women come to the doors of our programs, we cannot assume that we know what they want from groups unless we ask and listen to their responses” (1987, 7). The process of surveying women is ongoing and intrinsic to their method. Focusing on battered women, the project members solicit thoughts, questions, and concerns from women in bars, around a kitchen table at a shelter, on benches waiting for court hearings, in the hair salon. Through this process, they amass qualitative data for analysis. The thoughts and concerns voiced are not only descriptions of their experience, nor are they confined to specific instances of abusive behavior. They include questions, reflections, opinions, dilemmas. Some samples from their surveys follow (1987):

How do I deal with the fact that I don't like my son because he is like his father?

He doesn't hit me, but he break things, smashes walls, and says he isn't a batterer.

Sometimes emotional abuse is worse than physical abuse.

Does alcoholism cause battering?

Why do I feel guilty about staying with him?

Why do I feel guilty about leaving him?

He keeps accusing me of being a lesbian.

We've been to three different marriage counselors, and they all encourage us to do things I'm scared to do.

How do you deal with his threats to commit suicide?

The body of texts that they solicit serves as the material from which they abstract “themes.” Themes stand for the basic characteristics of one's situation put in terms of a general context of domination and oppression. Thus, the theme contains recognizable elements, since it was generated through interviews, but at the same time, it has been put in a larger social and political framework. Pence explains:

Themes broaden the base of a single issue. The facilitator looks for themes in the survey that allow her to pose a problem, the analysis of which will help the group make connections between seemingly isolated concerns. For example, specific abusive behaviors appear on the list twelve times. These behaviors are repeatedly mentioned in our surveys. This suggests that battering consists not only of physical abuse and threats, but also of abusive acts which reinforce the physical violence. If we examine each of the acts individually we may be misled as to its intent, cause, and impact. (Pence et al. 1987, 9)

Discovering recurrent motifs, the project members conceptualize themes that are intended to generate critical connections among moments of behavior that had seemed random, inexplicable, and hard to conceptualize as abuse. By this method, for example, the abuser who verbally degrades someone, denies her perceptions, breaks things, and punches the wall could be revealed as inflicting abuse. Themes provoke discussion and insight among women into what counts as abuse and how abuse is linked to other phenomena. The discussions also have the consequence of breaking isolation between women.

The project members select or devise codes that can be analyzed from three perspectives: “personal, institutional, and cultural.”

When the design team has decided that the theme is generative—that it allows for discussion on all three levels—the next step is to develop a code. A code is a teaching tool used to focus group discussion. It can be a picture, a role-play, a story, a guided meditation, a song, a chart or an exercise. The code provides a reference point for discussion and analysis … In designing a class the group facilitators prepare for their roles not by outlining a rigid structure that routes discussion from Point A to Point B, but by working to understand an issue more fully, so that as women we are able to make connections in our lives between our personal experiences and the world we live in. (1987, 10)

While the facilitator has determined the code, the character and direction of the process of analysis are open-ended. Within its original practice, then, the code is one step in an entire pedagogic and theoretico-political enterprise.

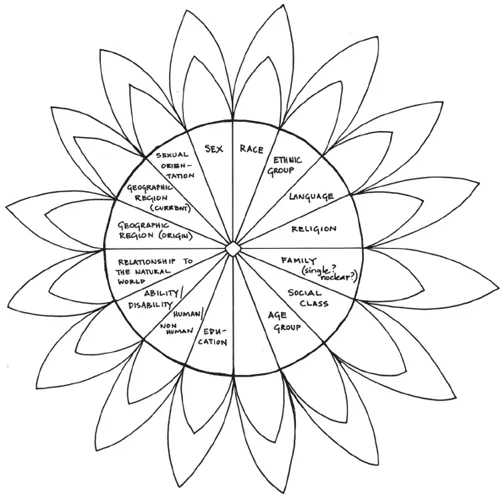

FIGURE 3. The Power Flower.

A facilitator commented on how the process of isolating codes made her change how she “reads” the world: “When I first started working on this curriculum I'd be hearing songs on the radio or seeing scenes in movies and on TV as possible codes. Suddenly everything had the potential to be a focus for discussion in a women's group” (Pence et al. 1987).

The Power and Control Wheel is an example of a code. Twenty years later, in 2010, Pence described the process: “So we went to all three of those groups over several months, and kept developing this thing over and over and we'd bring our little designs in, we had a lot of different designs to it and finally we came up with the one where we put the ‘violence’ around the outside and all the other tactics on the inside. We were trying to make it like a wheel where the violence held everything together. These tactics were … all part of a system” (Power and Control 2010). The Power and Control Wheel is one example of a code, one example among many (figures 3 and 4 show examples of other codes).

In the second part of the workshop, women furnish responses to a chart that asks them to think of instances in which social institutions and cultural mores support the violence. As it is conceived, women see how social institutions, such as the welfare office, housing officials, and cultural forces (such as traditional hierarchies within a community) collude in abuse. (Figure 2 shows the two charts in tandem.)

FIGURE 4. The Triangle Tool.

Here is a list of responses solicited from the part of the workshop that looks at institutional and cultural support for battering (1987).

Pastors tell women it is their role to be subservient to their husbands...