![]()

Part I

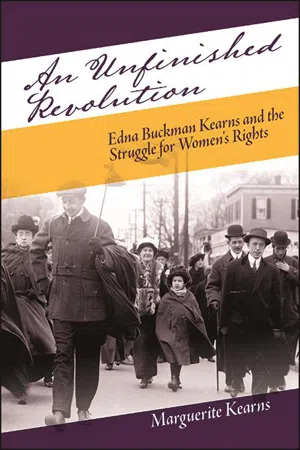

Parade memorabilia used by Edna Buckman Kearns.

![]()

Chapter 1

The March of the Women

No framed photographs of my maternal grandmother Edna Kearns hung on the walls of my childhood home. Family members spoke about her in soft tones or a murmur—and seldom. My mother told me that, as a child, she called her mother “Dearie.” This was scandalous, she said, because many people believed “Dearie” was a name associated with a “chorus girl.”

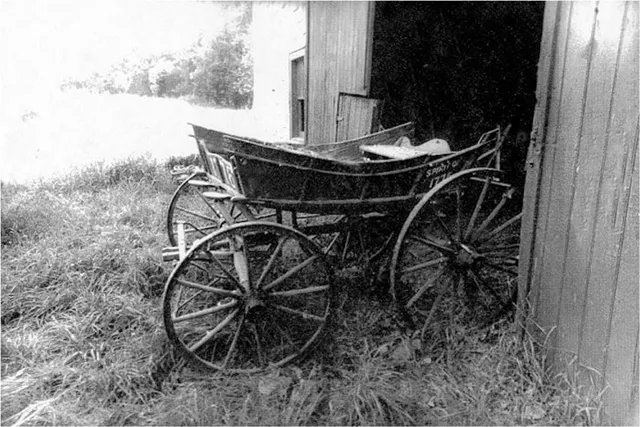

My grandmother’s names didn’t matter to me. Edna was a mystery, the grandmother I never knew who might have lifted me out of my isolation. Clues about Edna’s life were found in what she left behind. At age ten, I couldn’t wait to find out more about the horse-drawn suffrage wagon she used in women’s rights campaigning, known as the Spirit of 1776, stored in my grandfather’s garage. Edna’s archive of letters, speeches, and newspaper articles about women demanding the right to vote found a home in an old travel trunk, and my mother opened a box of Edna’s protest parade outfits for me to play dress up.

I dug into the assortment of musty-smelling fabric, lace, and long skirts packed away after my grandmother’s death. One summer afternoon I pulled a gauze ivory dress over my head to bond with my sweat, along with a purple, white, and gold sash fitting across my chest. I listened for Edna’s voice with my eyes closed and heard her faint voice in the distance.

“Hurry. They’re waiting for us to join the march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington,” she called to me from the mist. Hundreds of parade participants belted out a suffrage song to overpower taunts from the sidewalk. Edna fixed her eyes straight ahead while rough voices hollered: “Women shouldn’t vote. It’s not in their nature,” or “If they vote, they won’t have children,” and “Soon girls will be wearing long pants.”

The singing lowered to a whisper as I rubbed my eyes when my mother called me for a snack of celery sticks. I drooled over the possibility of lemonade and butter pecan cookies. On a day like this, though, nothing compared with wearing Edna’s dress—the same fabric that once touched her skin. I dragged her long skirts through the mud while marching with my knees lifted high.

“Here’s a photo of your grandmother,” my mother Wilma told me. Since I’d never seen a likeness of Edna, I lunged toward the image. It took me decades to find out that her photos were stored away because family members couldn’t process the grief of her death. They loved her. So did I. As my eyes caressed the waves of her hair, I stood before Edna in my pink halter and faded plaid shorts. In that moment, one word described her—stunning—even if her haunted eyes left me feeling unsettled. I sensed my grandmother was both frail and strong, engaging, and someone to be taken seriously.

Edna Buckman Kearns, “Dearie,” Rockville Centre, Long Island, circa 1915.

I picked up clues about Edna being determined and persistent, a sensible writer, and a quiet but forceful speaker. Her writing style was informed and direct. Few of her sentences, either spoken or written, were out of place. Her words moved without effort across a newspaper column. She could be both funny and perceptive in daily conversation. And according to my grandfather, she listened to others speak before contributing to a conversation.

“I didn’t make up the part about marching with Edna,” I said silently as a way of convincing myself of an authentic connection with my grandmother. I asked my grandfather, mother, and aunt the same question. “Do spirits of dead people return to earth?”

When I posed this and other unexpected questions, usually I got the same answer. “Why does it matter?”

“Just checking,” I said before disappearing into the shell where I resided as a child.

I pried out of Granddaddy that he considered Edna “borderline shy,” although he said this didn’t fairly describe her. “I’d also call her modest, thoughtful, someone who settled easily into silence and reflection. She liked socializing with others, but talking and sharing was mostly one to one.”

So Edna was reserved, like me, I said to myself. In my bedroom at home I pounded the palm of my right hand against the closet door in frustration. Words in my little-girl pink diary couldn’t bring my grandmother back. No matter what I did, the questions I asked, or the stories my grandfather told me, I couldn’t include Edna in my ordinary reality. I sensed her in a branch breaking on a dogwood tree outside my bedroom window. I counted my inhales and exhales when estimating how long it took her to march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, in 1913.

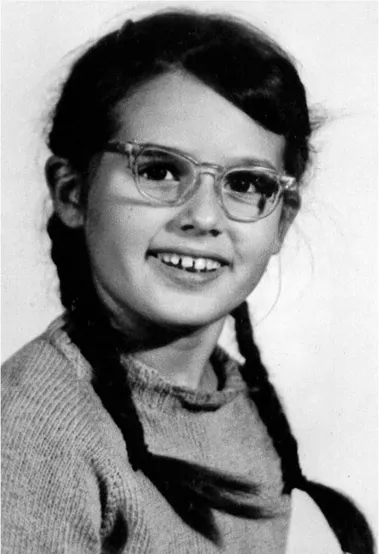

Marguerite Kearns, during the 1950s.

Shadowlike images of Edna standing on a soapbox on city streets followed me as patches of sunlight spread across my bedroom floor. I detected outlines of Edna’s face and hair falling lightly on her shoulders when a crescent moon came into view. I ran down the hill and up to my bedroom to visit with Edna under wool blankets after being dropped off daily by the school bus. It’s fair to say that my grandmother came to occupy much of my waking awareness as a child. I had to listen carefully to my mother and grandfather, though, if I ever expected to understand the complexity of Edna.

Because my grandmother died before my birth, I wondered if she ever suspected an unknown young person like me would take an interest in her someday. Perhaps I’d grow up and write like Edna. I’d tell the world about her, but I wasn’t sure if I could manage such a project. I wasn’t much of a storyteller, but I practiced on my sister. No one offered me a guidebook for how to survive to age ten and beyond. This translated to me taking everything my grandfather and mother said seriously.

Close family members like Edna’s mother, May Begley Buckman, might have predicted that Edna was headed in the direction of a job in a settlement house, a school, or library. May believed that if Edna found a husband with a serious interest in practicing equality in marriage, it would be possible for her to have a family, as well as make a contribution to history. Edna’s preference during her teens, however, was not to marry. She wanted to be free. When I heard this, I had no sense of myself or what marriage and freedom meant. Wilmer held the key to my understanding, or so I believed.

“Are your clothes clean enough to visit Granddaddy?” my mother asked when I was about to leave the house to hike the ten minutes to Wilmer’s.

“Absolutely,” I assured her.

After I arrived at Wilmer’s, he opened an overhead garage door to reveal the suffrage campaign wagon used in parades and as a speaker’s platform. Granddaddy repeated the story I’d already heard about the horse-drawn wagon Edna used in New York City and on Long Island in 1913. He called the wagon a “symbol” of freedom, a missing link between 1776 and the unfinished revolution of women’s rights.

“The wagon was groundbreaking for women,” he said, adding, “Sure, the votes for women movement wasn’t what it might have been if it had been centralized and well funded. It was mostly volunteer.” I had no idea what this meant. Granddaddy’s accounts of Edna and the wagon kept me spellbound during summer days when I wasn’t typing his novel and work in progress, Queen Bee, the Refugee, a tale of immigrants on a journey from the east to the west coast. I wondered if Edna kept certain things about herself a secret. Did she ever question whether Wilmer Kearns was right for her as a husband and partner? I wanted to find out.

On one of my visits, Granddaddy stared at me with one of his classic expressions with his lips closed tight. He swallowed hard, as if a golf ball were stuck in his throat. Occasionally he used a magnifying glass to read. When he did, his lips moved slowly. My grandfather didn’t always tell me what he was thinking, even though his chin and facial expressions sent a message of sadness. Wilmer missed Edna. I could tell this much. His relationship with her must have represented the deepest and most meaningful period of his life. How did I know? I figured this out from his sighs, the hints of tears gathering in the corners of his eyes. He didn’t marry again after Edna. And he definitely wanted to talk to me about her.

Spirit of 1776 suffrage wagon, circa 1980s.

I glanced over in my grandfather’s direction as he tipped back and forth in his rocking chair when telling me that, for Edna and himself, the women’s suffrage movement was no “snooty” affair with fancy ladies in low-cut gowns drinking tea, eating angel food cake, and engaging in old lady talk. Many activists took personal risks by marching in demonstrations and putting themselves on the line for women’s rights, just like Edna.

For many like my grandparents, entire families were involved in the agitation. “We were ordinary folks,” Granddaddy said. His worn reading glasses slid down on his nose. He might have changed lenses over the decades, but it seemed like he wore the same circular frames he purchased as a young man. He told me Edna spoke with her eyes—except when singing the English suffrage anthem, “The March of the Women”: “March, march, swing you along, / Wide blows our banner, and hope is waking.”

Women sang and marched together for good reason. There was a sensation of feeling strong and safe together when facing opposition. This thought caused my stomach to curl into a knot. I was shy, awkward, and felt like an outsider, a strange child in love with her invisible grandmother. I joined in with the marching songs, sat straighter in the chair in Granddaddy’s kitchen, and kept tune with the stanzas, the rhythms of feet tramping, and anxious hearts in thousands of throats.

“Edna and votes for women was the most glorious time in my life,” Granddaddy said. Then he became silent. He must have been picturing Edna in that moment, I decided, because he smiled.

![]()

Chapter 2

Wilmer Meets Edna

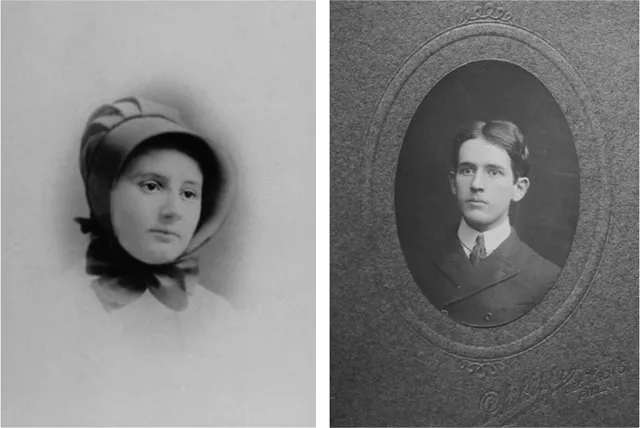

Edna Buckman met Wilmer Kearns on Logan Circle in the warm weather of 1902, not far from Center City in Philadelphia. I remember Granddaddy Wilmer telling me his breath collapsed in his throat when he noticed her. She more than caught his attention with a stream of sunbeams flooding her shoulders.

She carried a stack of line drawings of portraits and landscapes in her arms. And, he recalled, she wore a Quaker bonnet. After this radiant being dropped her drawings, they landed with a smack on the pavement and flew across the hard surface. On hands and knees, Wilmer retrieved every sketch and returned them to Edna, the opening he needed to introduce himself.

Edna May Buckman and Wilmer Rhamstine Kearns, circa 1903.

After Wilmer returned her drawings, Edna blushed and suggested something he never expected. “I’d love some company. I’m headed in the direction of Market Street.”

This was certainly an unusual woman, Wilmer decided, as the two walked along city streets, starting not far from where Wilmer shared lodgings with other business students at 235 East Logan Square. After classes, he and the other students played Parcheesi and rode bicycles in the direction of Independence Hall. They dressed in striped blazers and tight cycling pants.

Edna and Wilmer hiked toward the city’s center where a bronze statue of William Penn, Philadelphia’s Quaker founder, wearing a broad-brimmed hat, towered over them from the top of City Hall. As they walked, Edna and Wilmer spoke of their favorite authors. Edna liked newspaper reporter and columnist Margaret Fuller. Wilmer was fascinated with the naturalist Henry David Thoreau.

Wilmer kept his pace even with hers. He’d traveled this street before, but hadn’t fully experienced the coolness under trees lining the boulevard. As he glided along, he was aware of how Edna enjoyed leading as they covered the city blocks laid out by William Penn generations before. Walking together seemed natural. As Granddaddy related this to me, he said he didn’t feel his usual reserve. He presented himself as thoughtful and concerned. Edna came across to Wilmer as mature and aware.

She spoke in the Quaker plain speech to him—“thee” and “thy.” And she told him that this plain speech tradition started back in England when Quakers didn’t speak differently to those above them in social class, like kings and queens, or those below them. Quakers spoke to everyone in the same way. I was learning at my Quaker Meeting that all life forms on Earth were spiritually equal, including men and women as well as humans of all religions and backgrounds. To express in plain speech that everyone was equal was a radical practice in England during the 1600s. Granddaddy would learn to speak this way freely if he decided to spend more time with Edna.

“Philadelphia is an informal place where I don’t feel pressured,” Wilmer told her. Of the three big cities lined up in the East—New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC—a country boy like Wilmer Kearns found Philadelphia the least intimidating. At age sixteen, he had traveled from Beavertown, the town of his birth in Pennsylvania near Harrisburg, to Philadelphia, to study at Peirce, a business college.

I heard from Granddaddy that many historic buildings from the city’s earliest days were still standing on Market Street, a major thoroughfare in 1902. William Penn’s city plan fit between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, a grid laid out in 1682 when Edna’s Quaker ancestors arrived in Philadelphia from England with Penn on the ship Welcome. Their vision for a population center Penn called a Holy Experiment was rooted in ideals of religious freedom, an opposition to slavery, and peaceful relations with native peoples—all goals difficult to maintain over the long term in a city bursting with new residents from all over the world who didn’t necessarily share Quaker values. The Buckmans were the largest family group on the Welcome, and family descendants were determined to remember their roots by holding annual family reunions.

Statue of William Penn, 1894, before installation on the top of Philadelphia’s City Hall. Mechanical Curator Collection, Library of Congress.

Since moving to Philadelphia, Granddaddy said he noticed few Quaker women in traditional dress walking the streets. Unlike Edna in her bonnet and long gray dress, an increasing number of female descendants of early Quaker settlers wore conventional clothing. Quaker men also followed contemporary styles that gradually replaced their conservative dark coats and hats. Quaker plain speech was also on the decline. Because Edna wore her bonnet in public, it represented a gesture to convince her mother of her intent to live according to Quaker faith and values.

“Will thee stay here after finishing school?” Edna asked Wilmer after they reached Market Street.

“I’ll be off to New York where the pay’s better,” he told her.

Wilmer didn’t know much about Quakers, so he trained his ears to ...