![]()

1

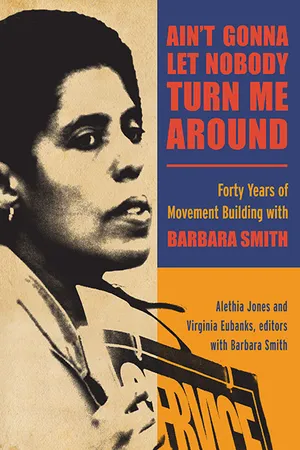

Chronicling an Activist Life

Virginia Eubanks and Alethia Jones

We started Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around: Forty Years of Movement Building with Barbara Smith in 2008, at the height of the sub-prime mortgage crisis and in the midst of the ongoing economic collapse. The devastation to communities and families in the United States called into question freemarket capitalism and representative democracy. By 2013, a flowering of social justice organizing and an upswell of courageous and principled action appeared around the world: the Arab Spring and other anti-totalitarian struggles in the Middle East and North Africa; the Puerta del Sol Square occupation of “Los Indignados” in Madrid, Spain; protests by tens of thousands of people in Britain and Greece against draconian austerity measures; and Occupy Wall Street, which inspired hundreds of occupations in cities across the United States and the globe.

Occupy Wall Street, one of the most hopeful recent efforts in the United States, was nevertheless beset with issues of classism, sexism, racism, and homophobia. It is not the first movement to earnestly struggle with these issues, and it won’t be the last. But how do the organizations, coalitions, and movements we are building attend to issues of hierarchy, leadership, and transparency? How do we build new ways of being with each other that incorporate fairness, respect, and accountability across our differences? How can we pursue strategies and construct organizations that embody the futures we wish to create? Attention to these matters is at the heart of Martin Luther King Jr.’s call to create “beloved community” and of Barbara Smith’s efforts to work with political movements to create a more just world.

This book is not a memoir, a biography, or a reader. It is a reflection and a conversation. Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around samples a lifetime of political work and commitment to liberation struggles, providing a mixed-media collage of voices and experiences from a variety of movements that, we hope, conveys useful lessons about the gritty work of pursuing social justice. The book uses Barbara Smith’s life and work to dissect, analyze, and derive lessons from the freedom struggles she experienced, shaped, and supported. Often, we critique the hierarchies “out there” while ignoring how we internalize them and reproduce them “in here,” in our movements and institutions. This has real consequences for organizing. One result is that the most privileged among us—those closest to the white, middle-class, heterosexual, male, able-bodied ideal—often reap most of the social status, political rights, and economic benefits fought for by people’s movements. Barbara Smith’s membership in multiple oppressed groups—Black, female, lesbian, working class—combined with her anti-racist and anti-imperialist stance led her to operate from an approach that refused to see any group as disposable and to insist that all of her identities be respected. Then and now, she challenges movement organizers to pursue innovative strategies that promote inclusion and accountability, forging patterns different from the hierarchical and exploitative models that we have inherited. We have drawn from her movement-building work and her participation as a scholar, organizer, writer, publisher, elected official, and activist. The documents and interviews juxtaposed in this book illustrate direct resonances between the current historical moment and the fervent movements for Civil Rights, Black feminism, women’s liberation, peace/anti-war, and gay and lesbian liberation that shaped the 1960s and 1970s.

Activist Grace Lee Boggs argues that the next revolution is not only about massive, visible protest in the streets—though some of the largest demonstrations the world has ever seen have taken place in the last decade—but about cultural change that allows us to combine spiritual growth, healing, and practical actions to reinvent the material and political reality of our daily lives. In The Next American Revolution: Sustainable Activism for the Twenty-First Century, she writes,

All over the world, local groups are struggling, as we are in Detroit, to keep our communities, our environment, and our humanity from being destroyed by corporate globalization…. Most of them are small and barely visible, but together they are creating the largest movement the world has ever known…. This movement has no central leadership and is not bound together by any ism…. But they are joined at the heart by their commitment to achieving social justice, establishing new forms of more democratic governance, and creating new ways of living at the local level that will reconnect us with the Earth and with one another. (Boggs and Kurashige, 2011: 42)

In her four decades of activism, teaching, and publishing, Barbara has grappled with some of the most difficult dilemmas faced by broad-based diverse movements for social change. Her faith in sweeping political change—the belief that massive shifts in consciousness, institutions, and power can occur at any moment—is founded in her own experience where again and again, so-called ordinary people make history. This book offers lessons from that experience intended to help us all work more deeply to secure liberation for everyone in the next American revolution.

In some ways, this book is “typical” Barbara. You will learn about her, but the book is really about the freedom struggles to which she has devoted her life. So many sisters, mothers, aunts, godmothers, grandmothers, sista friends, girlfriends, and others have inspired us because they stood up for our dignity and gave voice to our humanity and dreams. When they weren’t allowed in the front door, they used back doors, side doors, windows, alleys, and every which way to make change for our communities. Like other dedicated grassroots activists, Barbara attends too many meetings, forges ties across many players, strategizes and analyzes to identify points of leverage, creates new initiatives and programs, and when needed, puts herself on the front line to bring about meaningful social and political change. She traces her activist lineage to Black women—like Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, and countless others—who spoke truth to power in order to free their people and to bring all humanity closer to creating a just world. She roots herself in the legacy of Black female movement activism and its distinctive mode of action, which is tenaciously committed, constantly present, and fundamentally humane. The Black feminist movement that Barbara helped to build in the 1970s grew from a tradition that existed for centuries and will continue into the future as long as injustice exists.

So many of these glorious women are unnamed in our history books and their stories are not told. Barbara sees this grassroots movement-building work as historically significant. As a scholar, writer, and publisher, she sought to preserve movement history whenever and wherever she could, and her devotion to leaving a historical record makes this book possible. Over the past four decades, Barbara’s work on the front lines of a diverse array of movements has produced over two hundred books and articles. We selected the best and hardest to find pieces and combined them with a dozen new interviews commissioned exclusively for this project. In bringing together these otherwise scattered remnants of struggles and strategies into one place, we seek to facilitate a new generation of learning and leadership.

The decades Barbara spent insisting on full inclusion hold lessons others will find useful. The resulting truths may be uncomfortable, but, as Barbara says elsewhere, they are ultimately “truths that never hurt” (Smith 1998). The anxiety and discomfort these truths may provoke are simply growing pains that come from a deepened understanding and awareness of the world around us. We hope the book inspires your quest to fight for social justice in a world that is both riven with inequalities yet filled with endless possibilities for freedom.

Lessons in Movement Building

After mining the archives, talking to Barbara’s contemporaries, and listening in on the interviews conducted for this project, we identified core themes that operate as key touchstones for the entire book. We share them explicitly here. We offer them not as a “how to” primer that lays out a blueprint for growing social movements but as a “what to ask” guidebook to fundamental questions and ideas that social justice practitioners should grapple with to pursue their work with heightened integrity, accountability, courage, and humor.

We do not claim originality. The eight points we identify are grounded in the principles and practices of Black feminism that Barbara and her colleagues spent decades articulating. Black feminism originates with Black women’s experiences. The commitment to eradicate the injustices committed against Black female bodies and psyches creates a unique political analysis and practice. But this approach is not essentialist; it does not assume that membership in a biological or demographic category automatically confers an oppositional consciousness. Instead, Black feminist analytical methods pay close attention to the particularity of lived experiences. Consequently, we learn by analyzing our relationship to, or membership in, oppressed and degraded social groups. We also learn through our collective efforts and struggles to transform our experiences with injustice into sources of liberation, freedom, respect, dignity, joy and love. By highlighting them here, they serve as guideposts to help readers navigate through the rich array of perspectives and experiences shared in this book.

The eight points consist of four conceptual pillars—identity politics, coalition building, intersectionality, and multi-issue politics—and four core practices—awareness, integrity, courage, and redefining your own success. We see the pillars and practices as matched pairs where a key political principle is joined with an individual behavior that strengthens one’s ability to operate effectively in constructing each pillar. These eight points allow us to deepen movement building and enrich political consciousness.

Identity politics insists that the most insightful analysis of power often arises from a deep knowledge of the material circumstances of oppressed people’s lives. That means understanding where we come from, our identities, and the forces that shape us. To do so requires cultivating awareness by deepening our capacity to examine our own identities. Awareness helps us gain consciousness of the structures of privilege and oppression that permeate our lives. We experience our humanity through our distinct embodiment—the time, place, gender, race, nation, class, sexuality, physical body, age, languages, and political and social culture that we inhabit. It is imperative to know, understand, and respect that all people have unique social locations from which they experience the world. With awareness we become more responsible in our actions.

The dominant culture holds that to name our specific social location is to be exclusionary, to be narrow, to limit what is possible. Black feminists demonstrate the opposite, that naming can be liberatory. Instead of colorblindness, Black feminists pursue universal human rights grounded in the distinct histories of actual people. As argued by members of the Combahee River Collective, for example, a society that respects Black women is a society with institutions and people who have the capacity to be just, inclusive, and fair to everyone without compelling conformity to a single standard. Creating such a society requires a most thorough revolution of the institutions and cultural practices that assign worth and privilege.

The second pillar, coalition building, connects the hard work of knowing ourselves to the even more difficult task of working with others across difference. Coalition building asks us to reach outward from our individual and local experiences to create connections and shared agendas with others nationally and globally. As Barbara says in “Where Has Gay Liberation Gone?”: “How limited would my politics be if I was only concerned about people like me!” (p. 186). Battles for social justice are long hauls that require the combined efforts of a variety of movements to succeed. Because reaching out is complicated, dangerous work, it requires integrity. It entails the genuine pursuit of something other than self-interest and personal advantage, and acting in ways that are consistent with your internal values. Coalition work calls upon us to be honorable, sincere, and principled in our dealings, even when others are not. It requires us to approach others with a spirit of revolutionary optimism, despite past disappointments, because diverse connections are the only way to win in light of our enormous, shared, global challenges.

Intersectionality demands that we each account for our specific social location within interlocking webs of power and privilege and understand that different strands of injustice—racism, sexism, heterosexism, classism, xenophobia, trans-hatred, ageism, and others—are complexly interwoven. The concept of intersectionality*—which finds one of its origins in the Combahee River Collective Statement of 1977 (p. 45) as the phrase “interlocking oppressions”—holds that those who inhabit multiple categories of disadvantage cannot be served by single-issue politics or analysis. Because oppressions are experienced simultaneously, our political analyses and strategies must also be multidimensional. Intersectionality also suggests that each of us embodies a complex mix of disadvantage as well as advantage. Each of us must recognize and contend with the oppressor within, as well as value and nurture the aspects of ourselves that yearn for liberation. The recognition of this complexity can yield more nuanced organizing strategies than simplistic formulations that are rhetorically appealing but furnish little guidance to the complex inner dynamics of movement building. All of us have the capacity to reinforce oppression or to further liberation. Our choices and our analysis deeply matter.

Choosing to speak about identity can unmask many taken-for-granted social, economic and political conventions that affix categories of worth. Thus, this pillar takes enormous courage, a determination to look at difficult subjects and to speak the truths that you see. Truth telling means identifying root causes of problems; speaking the reality of our experiences in the service of justice and freedom, even when it’s inconvenient; and not being afraid to be challenging when necessary. Barbara has repeatedly chosen to speak uncomfortable truths. These truths are the foundation on which institutions and attitudes that respect those who are too often disrespected, neglected, and exploited can be built. The costs of telling the truth in the face of a status quo based on falsehood are real, and the intellectual and political work necessary to create broadly representative, multi-issue coalitions for social justice should not be underestimated. But earnest engagement is fundamental. These truths are often unwelcome and can inspire backlash and social recrimination. We chronicle some of the costs that Barbara has borne as a result of her courage in the chapters that follow.

“Each of us must develop the capacity to recognize and contend with the oppressor within, as well as to value and nurture the aspects of ourselves that yearn for liberation.”

Finally, multi-issue politics insist that we not prioritize the liberation of one group of people over any other and that we deliberately work together to dismantle overarching systems of oppression, not just to seek rights and benefits for a single group or victories on a single issue. All justice-seeking interventions must simultaneously attempt to eliminate economic exploitation, racism, sexism, homophobia, and violence in society at large. If our aim is to bring transformative changes in society, then we must be willing to redefine success away from narrow, temporary, or qualified gains. We must move beyond a focus on winning a law, election, or court case here and there and pursue instead the genuinely inclusive, democratic politics that we seek to build. In fighting for social justice, we pursue liberation for everyone. To do so, we need to see conditions for what they really are and also to forge different ways of being and acting. As the Black Radical Congress Principles of Unity state, “Our discussions should be informed not only by a critique of what now exists, but by serious efforts to forge a creative vision of a new society” (p. 205).

Black feminism challenges us all to forge effective alliances for social justice across difference because our futures are bound up in each other. Black feminism is grounded in an identity and operates as a political practice. It is an active commitment to fighting an exploitative and dehumanizing power structure. In order to achieve full humanity for all people, dominant cultural messages of inferiority imposed upon those marginalized from the mainstream for being the “wrong” race, gender, ethnicity, sexuality, or class must be combatted; for those who derive power from conforming to the status quo, dominant cultural messages of superiority must be excised. Liberation for everyone or liberation for no one is a statement of strategic and moral fact.

Why We Did It and What We Learned

Alethia

When Barbara invited me to edit this book, I welcomed the opportunity to trace her journey from activist to elected official. I met Barbara when she was a member of Albany’s Common Council, the legislative body of New York State’s capital city. She soon guest-lectured in my graduate class, Inequality and Public Policy. “How,” I wondered, “did a member of the legendary Combahee River Collective and a pioneer of identity politics find her way to public office?” As an urban politics scholar and practitioner, I am always delighted when grassroots activists deploy the principles, practices, and skills forged in a life of movement building toward the conventional political arena. Major progressive shifts in politics and policy can result. I invited colleague and friend Virginia Eubanks to join this project because her background in women’s studies and her work on welfare rights and economic justice organizing complemented my strengths in race, ethnicity, and urban politics.

I was ra...