![]()

1

“If Men Should Be Wanted”

1907–1908

Early in 1908, Oswald Garrison Villard, the progressive editor and publisher of the Nation and the New York Evening Post, replied to a letter of invitation from the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, known as NAWSA, the Reverend Doctor Anna Howard Shaw. She asked him to speak at a suffrage convention in Buffalo, scheduled for October 15, a date, Villard replied, that was too far in the future for him to commit. On top of that, to “prepare an elaborate address” was out of the question, he said, as he was already “taxed to the limit of my strength.” But in the letter, Villard also proposed a fresh idea that had started to gain ground in Europe: the formation of a prosuffrage club composed exclusively of men.

These would be not just any men, Villard suggested, but those with the stature to rival his own as the wealthy scion of an illustrious American family of reformers and industrialists. Villard envisioned a group of at least one hundred members and many vice presidents meant to function mostly in name—those who could “impress the public and legislators.” That would mean men with influence in all the important avenues of thought and power, those self-assured enough to ignore the ridicule that public support for women’s suffrage was bound to draw. Such a membership, Villard said, could entice others in the same political, professional, social, and charitable circles to plunk down a dollar in annual dues and heighten their interest in the suffragists’ cause or at least lessen their derision, something much of the New York press did its best to foster. Villard initially reasoned that to do no more than announce the names of influential men willing to associate themselves with the women’s movement in such a direct and public way would attract good publicity and bring useful direct and subliminal support. “I have wanted to suggest this for a long while,” he wrote to Shaw, “but have feared that if I did suggest it the work of organizing would be placed upon my shoulders, and I cannot undertake a single additional responsibility, not even one that requires merely the signature of letters.”

In approaching Villard to address the convention, Shaw had been acting on word from Villard’s mother, the suffragist Helen Frances Garrison Villard, known always as “Fanny.” His mother had let it be known that her accomplished son was willing once again to stump for the cause. He had done so in his “maiden speech” in 1896 to the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association. Twenty-five at the time, three years after his graduation from Harvard, Villard was pursuing a master’s degree and served as a teaching assistant to “The Grand Old Man” of American History, Professor Albert Bushnell Hart. Villard used the occasion of his suffrage association speech to push for getting women the vote and to urge Harvard to start admitting women as a way to prepare them for their duties as citizens.

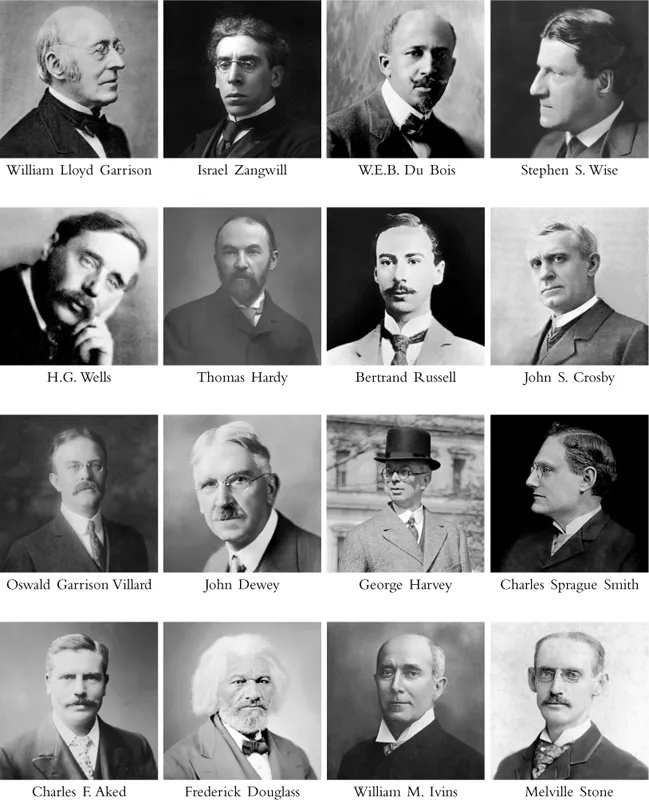

He was by no means the first American man to publicly support women’s suffrage. Frederick Douglass, the prominent abolitionist, had done so in a newspaper column as early as 1848, the week of the first Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, which he attended. His last public act the day of his death, February 20, 1895, was an appearance during a secret meeting in Washington, DC, of the Women’s Council. Anna Howard Shaw and his lifelong friend, Susan B. Anthony, had both escorted him to the platform, where he was roundly applauded And William Lloyd Garrison, Villard’s maternal grandfather, addressed the fourth women’s suffrage convention in Cleveland in 1853. A bold handful of other prominent men had also spoken out or written over the years.

In 1902, by which point Villard had succeeded his father, Henry Villard, as publisher of both the Post and the Nation, he joined other male supporters of suffrage in “An Evening with the New Man,” a Valentine’s Day–themed event at that year’s NAWSA national convention, in Washington, DC. Their appearance prompted some of the earliest headlines announcing men’s support for the women’s cause. In the Washington Post it was

MEN CHAMPION CAUSE:

WOMAN SUFFRAGISTS NOT ALONE IN THEIR BATTLE

And in the Washington Times:

NEW MAN’S VIEWS ON WOMAN SUFFRAGE

Shaw’s reply to Villard on February 6, 1908, made a point of reminding him of the great joy his remarks at that convention had given Anthony, who had died March 13, 1906, as had his “splendid stand for helpful reforms.” Yet in his earlier letter, Villard had already told her that it was not another convention speech that he had in mind. He was offering to use his considerable influence in “an appeal to the Legislature, if men should be wanted for that purpose.”

Such a proposal was not much of a reach for a man of Villard’s lineage. His father was a former reporter and war correspondent who made his money in railroads and bought the Post and its supplement, the Nation, in 1881. He also played a key role in the history of the railroad and the development of electricity in the United States. As owner of the Edison Lamp Company and the Edison Machine Works, which eventually became General Electric, the elder Villard subsidized Thomas Edison’s research for years. The younger Villard’s “close and binding” relationship with his mother was also clearly an influence. Fanny was a valued suffrage campaigner. “It gives me joy to remember,” she once said, “that not only my father, William Lloyd Garrison, but also my good German-born husband believed in equal rights for women.” It was a position her son had also embraced.

At the time of the younger Villard’s proposal to Shaw, the militant British suffragette Anne Cobden-Sanderson was winding up a much-publicized US speaking tour that took her to Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City between late October of 1907 and early January of 1908. Villard’s Evening Post, like all the major newspapers, gave her ample coverage. During those three busy months on the road, Cobden-Sanderson spent almost as much time insulting her American hosts as she did recounting her own harrowing saga of arrest and incarceration for demonstrating in front of the House of Commons a year earlier. Her conviction had put her away in the clothes of a jailbird in Holloway Prison, where for a month she scrubbed the floor of her eight-by-twelve cell and subsisted on weak tea in the morning, six ounces of bread throughout the day, and two baked potatoes with a cup of cocoa at night. She was quick to note to her American audiences that her prison record obliged her to slink over the Canadian border to enter the United States to avoid possible deportation had she been faced with the obligatory question of port officials: “Have you ever been arrested?”

Throughout her visit, in both public remarks and comments to reporters, Cobden-Sanderson scoffed at the comparatively slow pace of the US movement’s progress. Britain, she said, was “years ahead of American women in our fight for equal rights.” This she attributed in part to the new militancy of its women, an approach that her American counterparts had not yet embraced. American suffragists, she said, favored club life over action. Not the British. “We believe in doing real things not in talking about them,” she said, adding that her American sisters behaved in a manner far “too ultra-refined” to do the hard work that eventual victory demanded.

Cobden-Sanderson reserved her harshest critique for the American society dame who “steeps herself in the degradation of luxury. She adorns her person until I often am reminded of a Turkish harem. She measures all humanity by its clothes, as her husband measures all his fellow men by their wealth and their ability to acquire more wealth.” She scoffed at the poor judgment American women showed more generally, at the superficial way they evaluated leadership and thought about the world. (Months later, after her return to England, she would say that American women demonstrated “timid conventionality of thought” and the inability to grasp a profound idea.) She singled out the wealthy antisuffragist as one who “has no time to think of the vital questions of the hour, no civic pride, because she is too busy adorning her person and steeping herself in the luxury which deadens the soul to know what really is going on in the great pulsing world of the ‘under dog’—the stratum of humanity beneath her own.” To a reporter for the New York Times, she said, “I don’t want to be uncomplimentary, but really, I don’t believe the average American woman would know what to do with the ballot if she had it. She has had no political training whatever, and, as I have said, she doesn’t care for public affairs.”

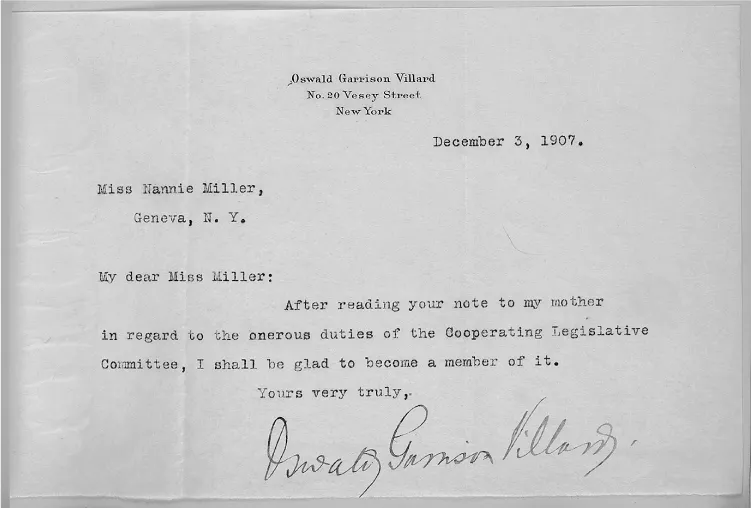

Villard, however, cared greatly about such matters, and on December 3, 1907, he had concretized a commitment to suffrage among his many causes. He joined the committee formed to lead the campaign to win support from the lawmakers in Albany. “After reading your note to my mother in regard to the onerous duties of the Cooperative Legislative Committee,” he wrote to its leader, Anne Fitzhugh Miller, who also headed one of the state’s largest political equality clubs in upstate Geneva, “I shall be glad to become a member of it.”

The major event of Cobden-Sanderson’s US tour came on December 12, 1907, when some four thousand people crowded Cooper Union to hear her speak at what was billed as the inauguration of “the greatest suffragist crusade in the history of New York.” The movement paragon Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had recently returned to the United States from England, where she had been working with her British suffrage sisters. Blatch introduced her British guest as “The Cobden” and proclaimed her a “martyr to the great cause of women.” In response, the Sun reported, “The house shook with applause.” From the podium, Cobden-Sanderson said the size and enthusiasm of the gathering had restored her hope for the American crusade. This time she denounced those women who did not want the ballot as “parasites at the top” and again railed against the superficiality of their “idle luxurious lives.” Press reports of the event devoted more column inches to repeating the British suffragette’s already well-reported insults than to her fresher remarks. They also devoted several paragraphs to expressions of disappointment that a widely rumored attempt to deport Cobden-Sanderson from the stage had not materialized.

Letter from Oswald Garrison Villard to Anne Fitzhugh Miller, December 3, 1907. (Miller NAWSA Suffrage Scrapbooks, 1897–1911; Scrapbook 6, 1907, p. 25; December 3, 1907; Library of Congress, Rare Book and Special Collections Division)

Two nights later, the New York Tribune covered her speech at a gathering of the Interurban Woman Suffrage Council at Memorial Hall in Brooklyn. The reporter chided the dozen men in attendance for their subservience, noting that two of their number had been reduced not only to walking the aisles for contributions but to strong-arming the other men present into offering up dollar bills along with the loose change in their pockets. The event’s female organizer had even sent them onto the platform to collect from the seated dignitaries, including the prominent Democrat John S. Crosby, who presided. Crosby “did not deign to make a speech,” the Tribune said, and “looked miserable indeed” after he misidentified the woman designated to second the resolutions. The headline:

EVE BACK IN THE GARDEN:

MERE MAN QUAILS AT INTERURBAN WOMAN SUFFRAGE MEETING.

As for Cobden-Sanderson’s remarks, the newest was a comment that she had never met so many timid people so afraid of consequences.

In a letter to Shaw, Villard put a positive spin on the British guest’s repeated barbs. “So far as Mrs. Sanderson is concerned,” he wrote, “while we regret her tactlessness, I cannot but feel that her visit has done some good, and that a certain amount of criticism of our American workers is justifiable.” More than that, something Cobden-Sanderson had emphasized throughout her speaking tour as another huge failing of the US movement seemed to have lodged itself in Villard’s eardrum. She spoke several times of the failure of American women “to enlist the sympathy of the men of America.” In Britain, she told the Boston Globe, “Nearly all of our most distinguished men are in favor of the emancipation of women.”

Cobden-Sanderson’s observations, along with the emergence of organized men’s groups in Britain early in 1907, were the foreground to the grand idea Villard presented in his letter to Shaw of January 7, 1908. “This leads me to one subject that has long been on my mind,” he wrote. “Why could not a Men’s Equal Suffrage Club be started here?” With the right secretary to recruit the membership and then charter and publicize the organization, he felt sure that such a group could be formed with “some excellent names on it.”

Soon after, a snide editorial in Villard’s New York Evening Post described as “rather startling” Cobden-Sanderson’s contention that the smug self-satisfaction of American women had complicated the work of the suffrage movement and added to its mission the need to first “create the very foundation of discontent on which all striving for reform is based.”

Shaw’s reply to Villard’s proposal came a good month after she received his letter. The idea for a men’s organization, she told him, was one the women’s movement had contemplated more than once over the years but had been wont to act upon. Hesitation, she said, always came down to the “undoubted fact” that the men who could do the most good for suffrage, those whose “influence and interest would enable them to draw to such a society others whose names would be really helpful,” were far too occupied with other matters to be of any real use. So many men, she explained, did not consider women’s suffrage a vital issue and those who did tended not to be in good standing with the men whose own positions would make them valuable as allies. Better not to attempt such a plan, she wrote, “unless the names secured would be in themselves helpful. Any others might constantly involve us in all sorts of isms, and we have more of them now than we can ward off with some of our over-zealous women.”

Another issue she did not mention was the ingrained opposition of serious, respected men like Woodrow Wilson, then the president of Princeton University with its all-male student body. Around this time, an interviewer paraphrased Wilson as having said t...