- 405 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

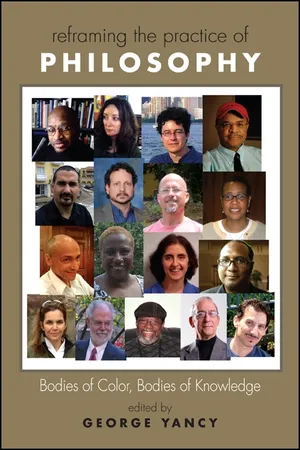

About this book

This daring and bold book is the first to create a textual space where African American and Latin American philosophers voice the complex range of their philosophical and meta-philosophical concerns, approaches, and visions. The voices within this book protest and theorize from their own standpoints, delineating the specific existential, philosophical, and professional problems they face as minority philosophical voices.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Reframing the Practice of Philosophy by George Yancy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Philosophy History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

COLONIZATION/DECOLONIZATION: PHILOSOPHY AND CANON FORMATION

CHAPTER ONE

ALIEN AND ALIENATED

I

Some years ago, while discussing with my continental philosophy class the famous claim by Walter Benjamin that the “hatred … nourished by the image of [one's] enslaved ancestors”1 provides the most powerful motivation possible for revolutionary action, I allowed myself to imagine (out loud) tying a rope around the well-known local statue of Christopher Columbus, pulling the statue over, and dragging it to the ground. The students sitting in the classroom, only one of whom was a Latina, stared at me with blank perplexity, their foreheads creased with the effort to understand. Some of them literally had their mouths open. How could I possibly make an analogy between the “discoverer” Christopher Columbus and the statues of tyrants that have been torn down in recent memory, from Saddam Hussein to Stalin? Have I lost my marbles?

As a Latina in the academic world of North American philosophy, I regularly feel that, indeed, I have lost, or am in the process of losing, my marbles. Neither my general lived experience, nor my reference points in argumentation, nor my routine affective responses to events, nor my philosophical intuitions are shared with most people in my immediate milieu. Miranda Fricker calls this situation “hermeneutic marginalization” to name the effects of inequality on the domain of socially available meanings.2 Like Roquentin, Sartre's anti-hero in his early novel Nausea, Latinas in philosophy often live without the sort of cultural and social recognition that would provide an uptake or confirmation of our interior lives, a fact that might indeed cause one to hallucinate, as he did, grotesque images when looking into the mirror.

In this chapter, I explore the problem of alienation for Latinos/as in academic philosophy in north America (a problem that is obviously analogous to the alienation of many other groups). Given our alienation, one might reasonably come to believe that assimilation is the natural and even just solution, since assimilation would decrease the experience of dislocation and enhance effective communication. But it remains open to question whether assimilation is either possible or desirable, or whether assimilation is even an alternative to alienation rather than in reality a form of alienation itself. If assimilation requires self-alienation from one's own hermeneutic horizon, for whom is it a solution? I suggest there are philosophical reasons, as well as political ones, to resist assimilation, given that coercive one-way assimilation forecloses what we might choose to read, teach, cite, and argue.

Yet on the other side, one might argue that if we militantly reject assimilation we will undoubtedly exacerbate our alienation from the Anglo majority in the profession. And anyway, what if assimilation simply involves an acclimation to majority conventions: Is that so unjust? Without assimilating, we cannot formulate arguments that will be meaningful or intelligible within the dominant domain of discourse, and thus we will not be able to expand or alter that domain. And one might argue further that the quest to resist assimilation embroils us in assumptions about neat Latino/Anglo divisions and “authentic” Latina/o dispositions. Can't a Latino just study Davidson if he or she wants to without having to engage in political self-examination?

II

These are the sorts of internal debates I suspect many of us have in our heads, especially as we enter the profession in graduate school and have to make decisions about dissertation topics, language-proficiency exams, and the cultivation of areas of competence and specialization. And our philosophical and political evaluations of these choices are always circumscribed by the pressing goal of academic success, which in our profession usually is measured simply by a tenure-track job at any institution anywhere for whatever pay is offered (as a former chair once told me, entering philosophy is like entering the priesthood; it requires a vow of poverty).

In order to even begin answering such questions about the harmfulness, legitimacy, or advisability of assimilation, we need to begin with an exploration of alienation. The particular level of alienation that I experienced may well be due to the sort of private, expensive, largely white-Anglo institution at which I was teaching at the time of the unfortunate Columbus statue-defacement example; I do not experience such alienation today teaching at the City University of New York (CUNY; now I just have the usual sorts of generational alienation from students who know more about reggaeton than about reggae). But outside of CUNY and a few other places, Latino students are scarce in U.S. higher education, no doubt affected by the fact that Latinos also are the group most likely to drop out of high school (I didn't know I was simply manifesting a statistical likelihood when I dropped out). Only 12% of Latinos in the United States graduate from college, as compared with 30% of whites and 17% of blacks (and all of these numbers—whites included—are of course much lower than they should be).3 Although we currently represent about 15% of the U.S. population (and rising), we make up less than 3% of the philosophy profession. Is there a relationship between Latino difficulties in educational institutions and our social and cultural alienation? Duh?

Africa and Latin America are alone among the continents of the globe that engender an alarming level of disrespect, ignorance, and contempt in north America.4 Military dictatorships, corruption, poverty, disease, and regularly occurring revolutions are the stuff of comedy when white North Americans land unhappily in one of these backward parts of the world, from Woody Allen cavorting with the revolutionary guerillas in Bananas, to Richard Dreyfuss haplessly forced to imitate a crazed dictator in Moon Over Parador—astoundingly in brown face. It is all good for a laugh. When Chinua Achebe's manuscript of his masterful novel, Things Fall Apart, was first reviewed by a publisher in 1958, Alan Hill, one of the editors, recalled the initial response: “Would anyone possibly buy a novel by an African?” Western reviewers later praised the book for its portrait of rural Igbo life, as if it was a piece of anthropological documentation. Its literary qualities were ignored.5

Can there be any coincidence about the fact that Latin America and Africa are viewed either contemptuously or paternalistically in the United States, and the fact that Latin American and African philosophy is invisible in Anglo-American philosophy curricula? Malcolm X motivated his pan-Africanism by the claim that the ways in which your nations of origin are viewed will determine the status of minority communities in the diaspora. African and Latin American intellectual cultures have not yet been accorded what Arturo Arias calls “the privilege of recognition” in the United States.6 This is to say that our philosophical traditions are not even represented badly in the mainstream U.S. philosophy curriculum: They are not represented at all. No wonder we hardly feel at home in institutions of learning, or that we are so often tempted to downplay our backgrounds, if not join in the derision of them.

For many Latinos/as I know who teach in colleges and universities, daily social alienation is so normal that they begin to see it as normative. One thing many of us have in common is that we have come a long distance to be where we are today—a social and cultural distance as well as a geographical one. The distance we have come is in fact rarely a mere matter of geography but more often a combination of geography, race and ethnicity, culture, nationality, first language, and class, some or all of which mark us as different from the majority. Given this distance, the alienation we experience might be interpreted—by others as well as by ourselves—as simply the expected price of travel.

Yet our very experiences of alienation can be quite useful at times in developing, and motivating, philosophical analysis, as well as in our pedagogy. When I teach the Marxist theory of alienation, I always use the example of the shirt factory where I worked as a piecerate seamstress (after I dropped out of college, another statistical regularity!). I was assigned to sew the top stitch on collars for a rate per piece that required me to produce one perfect collar every seven seconds of my eight-hour shift in order to make minimum wage. I use this experience to provide a vibrant picture of the four forms of alienation Marx describes in Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844: the alienation from the product I produced, from the process of producing it, from other workers, and from my own “species-being.” And yet I know that the use of this example, while vivifying the analysis and giving students something that helps them to both understand and remember Marx's ideas, risks alienating me from my students even further (and in ways Marx himself did not theoretically elaborate). The alienating aspects of working conditions that I describe for my students sometimes resonate with their own experiences of manual or otherwise proletarianized jobs. But there are other experiences of alienation that could prove similarly useful and illuminating although they may be less commonly shared, such as linguistic, religious, sexual, and cultural alienation. For example, the peculiar challenges of bicultural and cross-racial negotiations within one's own immediate family provide much interesting fodder for considerations of the effects of hermeneutic and phenomenological differences in baseline knowledge.

As philosophically useful as it may be, however, the experience of alienation has many negative ramifications both for one's personal well-being as well as for one's ability to perform one's job in the academy. If students do not understand what I am talking about, or perceive me as biased, “too” political, or an unlikely prospect to be a qualified professor of philosophy, my teaching evaluations might show signs of strain. My ability to work with colleagues may show similar strain if my point of view on matters of departmental concern cannot be made intelligible because of my hermeneutic marginalization. Fricker defines the “hermeneutically marginalized” as those who “participate unequally in the practices through which social meanings are generated” with the result that the experiences of the members of such groups “are left inadequately conceptualized and so ill-understood, perhaps even by the subjects themselves.”7 Hermeneutic marginalization disables participation in the construction of new meanings and new languages, which results in an interpretive incapacity to render one's experiences intelligible to others. To be marginalized from the construction of meanings and terms can produce what Fricker calls a “hermeneutic gap” of intelligibility, and she notes that this can affect content—the absence of available terms—as well as style, the manner in which we communicate. The adverse effects here tend to amalgamate and feed on each other, such as in the case she discusses of a woman who is sexually harassed before the second wave of the feminist movement invented this concept. Because the woman is unable to name her problem or its source in a way that will be understood correctly and taken seriously, she is then further cut off from social participation: She quits her job, cannot obtain unemployment benefits because she quit rather than was fired and cannot name the cause, and continues to fall in a spiraling effect. The end result of such amalgamating effects is a deflation of the very hermeneutic community that might be engaged in the work of developing new meanings and terms as well as more effective manners of redress.

III

These are the kinds of problems that create a motivation to assimilate. One is assimilated if one is absorbed or incorporated and thus comes to resemble the larger body, as when a food is assimilated when eaten. In this sense, assimilation is often distinguished from integration, which is a way of making room for a new entity, or of unifying a set of parts into a coherent whole. The term assimilao can connote a process of hybridization and bilateral influence, as Paula Moya argued using the famous lines of Tato Laviera's poem: “assimilated? Que assimilated, brother, soy asimilao.”8 But the dominant North American understanding of assimilation signifies a one-way accommodation, a process in which a minority adopts the majority mode of thinking, acting, even being. Given the receding percentages of the white Anglo majority, however, that “majority point of view” is losing its stability and meaningfulness; increasingly, the culture of U.S. urban life constitutes a pluritopic, rather than monotopic, hermeneutic horizon, inclusive of multiple and conflicting points of view, narratives of history, and opinions about the salience of race and the value of such things as markets, religious practice, and multiculturalism. These substantive differences sometimes result in differences in philosophical intuitions on topics as esoteric as intrinsic properties or the nature of ideal justice or the flexibility of linguistic contexts. I recently attended a talk on philosophy of language where Gricean concepts of implicature were being debated with the example of police interrogation techniques, and the philosophical differences in the room were interestingly correlated to those who referred to the subjects of police interrogation as “criminals” and those who referred to them as “the accused.”

What is clear is that the question of assimilation and alienation are not simply of concern to the minorities who must adapt, but also to the majority whose cultural and political dominance may be at risk. If we continue to assume that assimilation is the natural and rightful solution to alienation, and the justifiable price for traveling the distance from Latin America to the United States or from factory to college classroom, then we will foreclose the possibility of having a discussion about hermeneutic inequality and its effects on the norms of current practices in all areas of social life, including academic philosophy. I am suggesting, in short, that we shift away from debating the psychic cost of assimilation, and whether its benefit for individuals outweighs its costs to the collective. Rather, we need to be asking whether philosophy itself suffers when we accept assimilation as, to quote Baldwin, the “price of the ticket.”

Thus, the issues of alienation and assimilation are not only relevant to the daily grievances of our working conditions, such as those that concern social interaction, chilly climates, and one's ability for effective pedagogical communication. There also are philosophical issues at stake. I suggest that this claim is less antithetical to the traditions of Latin American philosophy. Such thinkers as Sarmiento, Bolivar, Martí, Mariátegui, Vasconcelos, Ramos, and others threw doubt on the assumption that the sphere of ideas operates above and beyond the fray of cultural imbrication. For Bolivar, for example, one cannot answer the question “What is the best or most just form of government?” in the abstract, without carefully assessing the local, historical conditions. Well before the American pragmatists, he argues that an idealized approach to political theory would be empty and useless. Similarly for Ramos, the nature of the self and mind cannot be approached as generic universals, but should rather be understood as constitutively related to the social conditions in which they emerge. Martí claimed that philosophy itself can be alienated.9 What this tradition suggests is that the cultural identity of philosophers will not be irrelevant to the philosophies they develop, a belief that is implicitly accepted in Anglo-American circles, as we teach about the “Scottish Enlightenment,” “British Empiricism,” and “German Idealism.” And yet rarely are the implications of this connection between philosophy and culture overtly explored.

In what follows, I explore both the philosophical and the everyday experiential issues involved in alienation and assimilation, as well as the interactions between these levels. In the conclusion, I suggest some remedies.

IV

When we consider the condition of Latinos in north American philosophy departments, we need to disaggregate between those from Latin America and those who were born and raised in the United States. We also might disaggregate further along region, race/ethnicity, and nationality, but this first distinction is highly significant.10 Latinos are among the most under-represented groups in philosophy, and if one eliminates from this group those who were raised and educated in Latin America, the numbers vastly drop. This has something to do with the likely class background this distinction tracks, but also may well be because Latin Americans, as opposed to U.S. Latinos, are likely to experience less culturally based alienation, of the sort that can deprive one of the conceptual repertoire necessary for a minimal understanding of one's own experience. That is, Latin Americans who grew up in Latin America will likely learn something of their own political, intellectual, and cultural history, will likely come into contact with some articulations of what it means to be Bolivian or Nicaraguan, or to be Quechua or mestizo. Despite the gender and racial hierarchies and exclusions, national narratives of latinidad assume that Latin American countries are sites of cultural and intellectual production.11

If Hegel is to be believed, all knowledge requires some level of self-knowledge given the ineliminable historical and cultural positioning of the knower. Knowing is a relational category, and one needs to train our critical analysis on both sides of the relation. It is just common sense that some self-examination is necessary in order to ensure that one's argumentative responses to philosophical ideas are not based on irrational prejudice, ideolo...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Inappropriate Philosophical Subjects?

- Part I: Colonization/Decolonization: Philosophy and Canon Formation

- Part II: Racism, the Academy, and the Practice of Philosophy

- Part III: Gender, Ethnicity, and Race

- Part IV: Philosophy and the Geopolitics of Knowledge Production

- Part V: Philosophy, Language, and Hegemony

- Contributor Notes