![]()

1

ARCHAEOLOGY AND MENTALITY: THE MAKING OF CHINA

DAVID N. KEIGHTLEY

The great problem for a science of man is how to get from the objective world of materiality, with its infinite variability, to the subjective world of form as it exists in what, for lack of a better term, we must call the minds of our fellow men.

—Ward H. Goodenough1

COMPARATIVE STUDY of the differing ways in which major civilizations made the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age has, in recent times, generally emphasized such common factors as developing social stratification, emergence of complementary hierarchies in the political and religious spheres, and complex division of labor.2 In China, the transition from a kin-based, Neolithic society to an Early State, Bronze Age civilization—represented by the Late Shang cult center (ca. 1200–1045 B.C.E.) at Yinxu in northern Henan (see fig. 1)—may be characterized in such universal terms. Increasing sophistication in tool production in particular, and in lithic, ceramic, and construction technology in general, may be associated with increasingly sharp distinctions in economic and social status, concentration of wealth, declining status of women, development of human sacrifice, and the religious validation of exploitation and dependency. By the Late Shang an elite minority of administrators, warriors, and religious figures was controlling, and benefiting from, the labors of the rest of the population.3

Such analyses show us how Chinese civilization followed certain general patterns of social development, how the early Chinese were the same as other peoples. But if we are to understand more deeply the development of the Shang, and of the classical Chinese civilization that followed, we also need to consider the features that made the Shang different.

The features which characterize early Chinese civilization include millet and rice agriculture, piece-mold bronze casting, jade working, centralized, protobureaucratic control of large-scale labor resources, the strategic role of divination, a logographic writing system, a highly developed mortuary cult, and the development of social values, such as xiao (filiality), and of institutions, such as ancestor worship and the custom of accompanying-in-death, that stressed the hierarchical dependency of young on old, female on male, ruled upon ruler. The complex manner in which these elements coalesced, fed upon, and encouraged one another lies at the heart of our understanding of Shang civilization.

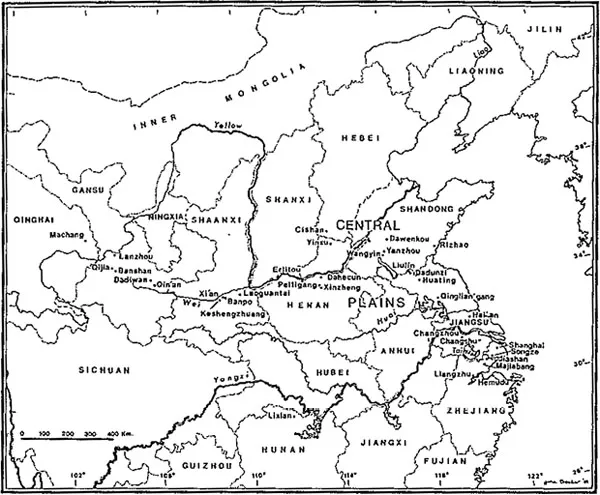

Figure 1 The major archaeological sites discussed in this essay.

All these and, no doubt, other features of early Chinese culture need to be studied comparatively and explained, that is, related genetically and structurally, to the other features of the natural and man-made environment if we are to understand what made China Chinese. The more modest intent of this article, however, is not to address such comparative questions directly but to suggest new ways of approaching the Chinese archaeological evidence as a preliminary to such comparative analysis.4 In what follows, I shall limit myself to the pre-Shang evidence, attempting to identify the particular features that reveal prehistoric habits of thought and behavior that were to play, I believe, a strategic role in the genesis of Shang culture.

I am aware that I occupy disputed ground in attempting to link artifacts to mentality. “New” archaeologists have declined to explain the past in mental terms, on the grounds that neither the thoughts nor the activities of individual actors are available to us.5 My own position is more traditional, in that I wish, so far as possible, to ask historical and cultural questions of the material data, directed to particular events and the meaning they had for their participants. This places me among the ranks of the cognitive anthropologists, as indicated, for example, by the epigraph at the head of this essay. As Ian Hodder has written:

All daily activities, from eating to the removal of refuse, are not the result of some absolute adaptive expedience. These various functions take place within a cultural framework, a set of ideas or norms, and we cannot adequately understand the various activities by denying any role to culture….

Behind functioning and doing there is a structure and content which has partly to be understood in its own terms, with its own logic and coherence.6

I believe that material culture expresses and also influences, often in complicated, idealized, and by no means exact ways, social activity and ways of thinking, and that the goal of archaeology must be comprendre as well as connaître. I do not use the word ideas in what follows, but I do attempt to infer, from pots and other artifacts, some of the structure and content of the mental activities that underlay the behavior of China’s Neolithic inhabitants. Readers must judge for themselves whether the risks taken in this exploratory essay are worth the insights gained.

The essence of my argument is twofold. First, I assume that the way people act influences the way people think and that habits of thought manifested in one area of life encourage similar mental approaches in others. I assume in particular that there is a relationship between the technology of a culture and its conception of the world and of man himself, that “artefacts are products of human categorization processes,”7 and that style and social process are linked.8 It is this assumed linkage that encourages me to think in terms of mentality, whose manifestations may be seen in various kinds of systematic activity. If it is true that “the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle [strongly] bear the imprint of the crafts of weaving and pottery, the imposition of form on matter, which flourished in ancient Greece,”9 and if pottery manufacture, in particular, can, in other cultures, be found to reflect social structure and cultural expectations,10 then we are justified in attempting to discern similar connections in the crafts of prehistoric China. Artifacts provide clues, incomplete and distorted by material constraints though they must be,11 to both the social structure and the mentality of those who made and appreciated them. To quote Hodder again, “the artefact is an active force in social change. The daily use of material items within different contexts recreates from moment to moment the framework of meaning within which people act.”12

Second, I assume that one of the essential features that distinguished Bronze Age from Neolithic mentality, in China as elsewhere, was the ability to differentiate customs that had hitherto been relatively undifferentiated, to articulate distinct values and institutional arrangements, to consciously manipulate both artifacts and human beings. This is not to claim that prehistoric man did not make distinctions or that he was not conscious of what he was doing. The difference is one of degree. In the prehistoric evidence, accordingly, I shall be looking for signs of enhanced differentiation, for signs of increasing order in both the material and mental realms, for signs of what Marcel Mauss called the “domination of the conscious over emotion and unconsciousness.”13

Two Cultural Complexes

With regard to the purposes of this paper, I believe that we can make considerable sense of the Chinese Neolithic without having to reconstruct, prematurely, the entire picture of its cultural development, desirable though the attainment of such a goal eventually will be. If we are not yet able to map the development of every Chinese cultural trait with assurance, and if, in particular, we are not yet able to determine whether similarity of traits in various Chinese sites and regions is homologous, implying genetic connection, or merely analogous, implying independent invention but convergent development, I nevertheless hope that this paper will demonstrate the importance of mapping certain, strategic traits by both space and time.

Even though it is important to think, both first and last, in terms of a mosaic of Neolithic cultures whose edges blur and overlap (see fig. 1),14 I believe that, for analytical purposes, one can—with all due allowance being taken for the crudity of the generalizations involved—still conceive of the Chinese Neolithic in terms of at least two major cultural complexes: that of Northwest China and the western part of the Central Plains, on the one hand, and that of the East Coast and the eastern part of the Central Plains, on the other.15 I shall, for simplicity, refer to these two complexes, which should be regarded as ideal types, as those of the Northwest and the East Coast (or, more simply, East). There were numerous regional cultures within these two complexes. In the sixth and fifth millennia, for example, cultures like Laoguantai, Dadiwan, and Banpo flourished in the Northwest; cultures like Hemudu, Qinglian’gang, and Majiabang arose in the area of the East Coast. The interaction between the two larger complexes is of great significance. By the fourth and third millennia, one sees East Coast traits beginning to intrude in both North China and the Northwest, so that the true Northwest tradition reaches its fruition during the third millennium in Gansu and Qinghai while fading away in the region of the Central Plains and even in the Wei River valley.16 As we shall see, the emergence of Shang culture in the Central Plains (ca. 2000 B.C.E.) owes much, though not all, to this infusion of elements from the East.

With assumptions and terminology thus established, I should now like to turn to the two central questions of this essay: what did the peoples of prehistoric China do? And what significant cultural conclusions can we draw from their activities?

Pottery Manufacture

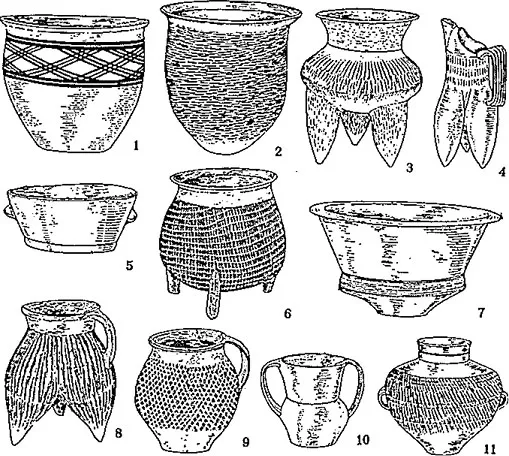

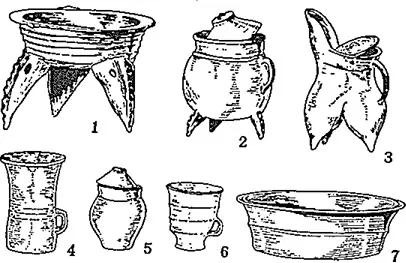

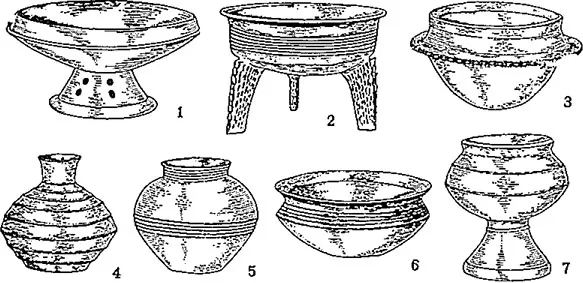

Broadly considered, the essential characteristics of the East Coast ceramic tradition (figs. 2–13) include the following features: 1) pots were unpainted; 2) angular, segmented, carinated profiles were common; 3) pots were frequently constructed componentially; and 4) pots were frequently elevated in some way.17 The ceramic tradition of the Northwest (figs. 14–15), by contrast, was characterized by a more limited repertoire of jars, amphoras, and round-bottomed bowls and basins, only a certain proportion of which were painted.18 What can these two ceramic traditions tell us about the mentality of, as well as the material constraints imposed upon, the potters who made the vessels and the people who used them?

Figure 2 East Coast pots, Longshan. Reproduced from Feng Xianming, et al., Zhong-guo laoci shi (A history of Chinese ceramics; Beijing, 1982), 15.

From the viewpoint of manufacture, the tectonic formality of sharp, angular silhouettes and the absence of rapidly painted surface decoration in the East (figs. 2–13) suggest deliberation and control, a taking of time to plan the shapes, to measure the parts, and to join them together. The interest in silhouette, frequently articulated or “unnaturally” straight-edged, rather than in surface decor, further suggests a willingness to do more than simply accept the natural, rounded contours of a pot.19 It suggests a willingness to impose design rather than merely accept it as given by the natural qualities of the clay. It suggests, as we shall see, that Eastern pots, by contrast with the “all-purpose” pots of the Northwest, were designed with specific functions in mind.

The existence of an East Coast disposition to manipulate and constrain is confirmed by a closer look at pot construction. Unlike the more practically shaped Northwest pots, most of which would have been built up holistically by coiling and shaping at one time, many of the characteristic East Coast pots—like the tall-stemmed bei drinking goblets (fig. 3, no. 6; fig. 6, nos. 1–6; fig. 10, nos. 12, 16, 17; figs. 11–13), the ding cauldrons (usually tripods; fig. 2, no. 6; fig. 4, nos. 1, 2; fig. 5, no. 2; fig. 6, nos. 10–20; figs. 8–9; fig. 10, no. 6), the dou offering stands (fig. 3, no. 1; fig. 5, no. 1; fig. 7, no. 4; fig. 10, nos. 3–5), and the hollow-legged gui pouring jugs (fig. 3, no. 7; fig. 4, no. 3; fig. 7, nos. 8–19; fig. 13) and xian steamers (fig. 6, nos. 7–9)—would have required the separate molding and piecing together of several elements—feet, stand, legs, spout, neck, handle, and so on, in a prescriptive method of manufacture. This distinction between holistic and prescriptive is of fundamental importance to my attempt to link artifacts to mentality.20

Figures 3–5 East Coast pots. Top: Dawenkou; center: Longshan; bottom: Majiabang. From ibid., 21, 22, 28.

The prescriptive, and thus componential, construction of pots21—which was inevitably involved whenever feet were prefabricated and added on to a vessel such as a ding cauldron, or whenever vessels were built up sectionally—appears to have developed as a significant method of manufacture in the Yangzi delta around the year 4000 B.C.E. In the fourth and third millennia, componential construction was frequently used in the Daxi and Liangzhu cultures of the Middle and Lower Yangzi and also in the Dawenkou culture area of Shandong and northern Anhui. It was present in the Late Neolithic Middle Yangzi culture of the third millennium, where, although the potter’s wheel was in use, most pots were still handmade, and where large ones were frequently built up by coiling, being produced in sections with appliqué bands being added where the parts were joined.22 It was also present, of course, in the Central Plains and Northwest as East Coast pot forms became more prevalent (see note 16).

A simple but elegant tripod from Songze (ca. 4000 B.C.E.) illustrates the nature of East Coast componential construction (fig. 8): 1) the bottom was shaped first; 2) the sides were then built up on a slow wheel; 3) the rim was luted on; 4) legs were fabricated separately and 5) appended to the body. It should be noted that whenever tripod legs or ring feet, which were both characteristic Eastern features, were added to a bowl, the body of the vessel would presumably have been turned upside down at that stage of manufacture. Such inversion would have involved what may be seen as more deliberate manipulation than the pott...