- 195 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

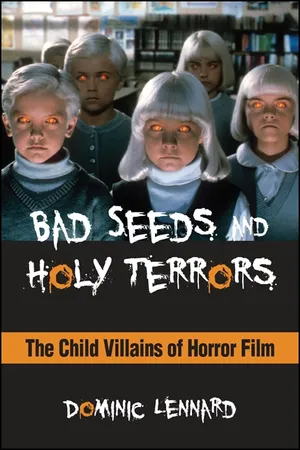

About this book

Since the 1950s, children have provided some of horror's most effective and enduring villains, from dainty psychopath Rhoda Penmark of The Bad Seed (1956) and spectacularly possessed Regan MacNeil of The Exorcist (1973) to psychic ghost-girl Samara of The Ring (2002) and adopted terror Esther of Orphan (2009). Using a variety of critical approaches, including those of cinema studies, cultural studies, gender studies, and psychoanalysis, Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors offers the first full-length study of these child monsters. In doing so, the book highlights horror as a topic of analysis that is especially pertinent socially and politically, exposing the genre as a site of deep ambivalence toward—and even hatred of—children.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors by Dominic Lennard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Reaching the Age of Anxiety

The 1950s and the Horror of Youth

THREATS TO THE IDEA OF THE innocent and vulnerable child were perceived and denounced at various points in the first half of the twentieth century. However, in the years following World War II childhood became increasingly visible as a distinct and potentially troubling category. Youth culture was permitted to flourish after the Great Depression disconnected young people from their traditional economic roles, and enrollment in high school became normalized. The popularization of automobiles also gave teenagers increased mobility and freedom to congregate outside of a supervisory adult gaze. Concerns were raised particularly in light of an unprecedented national concern over youth crime. The actual increase of juvenile crime in the years following the war is uncertain (see James Gilbert’s A Cycle of Outrage for detailed discussion of its uncertainties), but the public was easily drawn into the narrative of a dramatic increase with a number of cultural culprits. Centralized in the panic over wayward youth were the spread of mass media, namely television, an increasingly distinct youth culture (including rock and roll), and the popularity of comic books. Senator Estes Kefauver’s 1955–56 report on comic books and juvenile delinquency (which preceded a similar inquiry into television) nervously observed the new ubiquity of the mass media:

The child today in the process of growing up is constantly exposed to sights and sounds of a kind and quality undreamed of in previous generations. As these sights and sounds can be a powerful force for good, so too can they be a powerful counterpoise working evil. Their very quantity makes them a factor to be reckoned with in determining the total climate encountered by today’s children during their formative years. (“Comic Books and Juvenile Delinquency”)

Providing expert testimony on the relationship between comic books and juvenile crime before Kefauver’s Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency was Dr. Fredric Wertham, author of Seduction of the Innocent, an excoriating explanation of the effect of comics on the educational, social, criminal, and sexual trajectories of their young readers. In reference to the popular crime comics of the era, Wertham wrote that while “almost all good children’s reading has some educational value, crime comics by their very nature are anti-educational. They fail to teach anything that might be useful to a child; they do suggest many things that are harmful” (90). For Wertham, censorship of comics was urgently needed for children’s mental and social health and thus the health of society as a whole. For example, Wertham outlined what he called the comic-book syndrome, which occurs “in all children in all walks of life who are in no way psychologically predisposed” (114). The “syndrome” provided a direct narrative in which the process of reading and acquiring comics led to juvenile delinquency: the comic books’ antisocial subject matter aroused in the child antisocial impulses for which he or she felt guilty—consequently, as Wertham saw it, further comics were obtained clandestinely through dishonesty or theft.

Having infiltrated all the way into the “safe” domestic sphere, television was considered a threat through the sexual or violent content of its programs as well as through its ability to address children directly, bypassing the adult as caretaker of children’s “appropriate” knowledge. While the new medium was seen as a potentially useful domestic tool through its ability to promote family values, moral panic over its uncertainties achieved a powerful foothold in the cultural imagination. Joe Kincheloe observes that

[t]he popular press circulated stories about a six-year-old who asked his father for real bullets because his sister didn’t die when he shot her with his toy gun, a seven-year-old who put ground glass in the family’s lamb stew, a nine-year-old who proposed killing his teacher with a box of poison chocolates, an eleven-year-old who shot his television set with his B. B. gun, a thirteen-year-old who stabbed her mother with a kitchen knife, and a sixteen-year-old who strangled a sleeping child to death—all, of course, after witnessing similar murders on television. (117)

Following (and in many cases contributing to) the public concern with delinquency, cinematic representations of youth changed dramatically, providing for children’s passage into horror cinema as villains. Not that the horrifying child was entirely new; it is certainly true that prototypes of horror’s child villain predate this era. In William Blake’s poem “The Mental Traveller,” the narrator conveys an immense but elusive dread at the spectacle of a frowning baby who parallels the infant Jesus. In Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw, a well-meaning governess struggles with the veiled truth of her ward’s delinquency, a trait strikingly posed against his idealized appearance. Similarly, it would be a mistake to view pre–World War II cinematic representations of children as entirely one-note in their affirmation of innocence; as Timothy Shary points out, “[t]he very association of children with innocence had been challenged throughout many films of the 1930s and 1940s, especially as studios developed films about social problems during the Depression” (15). However, it was in the 1950s that the cinematic questioning of childhood innocence attained new force with a plethora of films of greater and lesser repute focusing on juvenile delinquency. It was in this period, and via these concerns, that child villainy achieved the currency and force that allowed it to solidify into an enduring horror theme. The year 1956 saw the release of the archetypal child villain film, The Bad Seed. While it clearly drew on the moral panic juvenile delinquency sparked, The Bad Seed also strikingly decontextualized the deviance it depicted, shifting the discourse that surrounded the troubled child: a social problem interwoven with complex cultural developments became a problem of inherent evil. This chapter traces horror’s child villains to the cycle of juvenile delinquent films of the 1950s, highlighting the cultural changes of the time that rocked categories of childhood. It also identifies The Bad Seed as a watershed film that transferred cinematic questioning of innocence from social commentary to horror, directing representations of transgressive children into new and more volatile forms.

Troubled Teens: The Juvenile Delinquent on Film

As Shary points out, “There was no moment when the [juvenile delinquent] fixation of the 1950s begins in earnest. Certainly movies like Knock on Any Door were harbingers, yet not many delinquency tales were made before the mid-1950s” (50). Yet by the decade’s close, a multitude of pictures of greater and lesser quality had been produced. Most influential and noteworthy in the cycle were certainly The Wild One (1953), Blackboard Jungle (1955), and Rebel Without a Cause (1955). In The Wild One, the delinquent was portrayed with fundamental sympathy, his rebellious appeal and redemptive possibilities combined in the leader of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club, Johnny Strabler (Marlon Brando in possibly his most iconic role, and in a performance of standoffish naturalism that sent waves of influence through the world of young male actors). Upon arriving with his goons in the town that will be subject to their mayhem, and despite his status as leader to whom club members consistently defer, Johnny swiftly and sulkily distances himself from his gang, taking refuge in the local tavern. He carries through the film like a fetish a trophy stolen from a motorcycle race, a token of his disaffection; Johnny claims to be the legitimate owner of the prize yet makes no attempt to conceal its stolen origin, flaunting it as a genuine token of his social worth as well as an obnoxious parody of his desire for acceptance. In The Wild One, we can see a number of changes to youth’s conceptualization that are characteristic of the era. Aggressively foregrounded is the visibility of a youth subculture (in the form of motorcycle gangs) as well as a young man’s ambivalent desire to be accepted by an increasingly self-absorbed adult culture, a self-absorption elaborated most memorably in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). More than mere anxiety over an increasingly autonomous youth culture, the gang’s thunderous arrival—swarming into the town like black leather hornets—also gestures to the mobility granted by a surge in youth consumer power. In Western Europe and the United States, the 1950s firmly established young people as a crucial consumer demographic. Shary writes that teenagers’ acquisition of cars “gave them new senses of independence and mobility. Now teens no longer had to stay within the confines of their hometown and congregate around a single hangout” (17). The new youth consumer power is troublingly articulated upon the gang’s arrival in town: in the tavern, they drink rowdily and to excess, their patronage encouraged by the bar owner, although we know very well what it will lead to. The paternalistic townsfolk’s moral panic eventually fixates on Johnny, who is engaged in shedding his tough-guy affectations through his relationship to doe-eyed bartender Kathy (Mary Murphy), who sees in Johnny’s mobility the chance to escape her dreary, small-town life.

Structuring the audience’s identification more closely around adult authority, one of the most significant films to engage with the unease and increasing visibility of juvenile delinquency was Richard Brooks’s adaptation of Evan Hunter’s novel Blackboard Jungle, which follows the struggle of soft-spoken English teacher Richard Dadier (Glenn Ford) to engage the volatile teenagers of North Manual, an inner-city boys’ school. The film opens with an intertitle that makes explicit reference to the public concern over juvenile delinquency, noting its disturbing extension into an otherwise admirably well-meaning school system. However, the film was also denounced from some quarters as part of the problem, partly because of MGM’s own marketing, which sensationalized its treatment of delinquency, capitalizing on its shock value (see Golub 25–26). Blackboard Jungle opened with Bill Haley and his Comets’ “Rock around the Clock,” propelling the track to popularity and signaling the cultural ascendance of rock and roll as emblematic of a distinctive and troubling youth culture, imbued with sexuality and rebellion. Comics, too, are part of the problem in the film: Dadier expresses his support for anything that will “get [the students’] minds out of comic books,” his role as an English teacher well positioned to counter this apparently toxic non-literature. Ultimately, Dadier is able to get through to his class—including such young talents as Sidney Poitier, Rafael Campos, and Paul Mazursky—after the isolation of bad apple Artie West (Vic Morrow), a villain who epitomizes the insidious influence of gang culture.

Despite its flattering appraisal of a school system that pays tribute to American communities and belief in its young people, Blackboard Jungle paints a rather bleaker picture of the state of the American education system in the postwar years. North Manual’s teachers are scared, careless, or aggressively cynical (the shop teacher [David Alpert] contemplates assembling a disguised electric chair with which he will immolate his whole class). Adam Golub writes that “Dadier is frustrated by unmotivated students, burned-out colleagues, an unsupportive administration, inadequate school facilities, and an ineffective teacher education program, which he feels did not prepare him to deal with low-achieving students or classroom discipline” (21). In an assembly at the start of the film, the students are barked at via microphone by Mr. Halloran (Emile Meyer), whose manner immediately signals North Manual’s pedagogical inferiority in having bred and supported an educator in whom the new teachers struggle to imagine any nurturing or pedagogical spirit: “What does he teach?” one questions. In his address, Halloran oscillates between the sarcastic humor of a penal officer and imperatives that clarify his power. Dadier’s uncomfortable recollection that Halloran teaches “public speaking or something” contrasts tellingly with the man’s frothily indecorous greeting: presumably Halloran has surveyed and quantified his audience and determined that they do not qualify for even a snippet of his elocutionary skill. Childhood, in Brooks’s film, is under cynical review. Golub has also persuasively demonstrated that Blackboard Jungle, rather than a film merely reflecting the terror of postwar juvenile delinquency, is also symptomatic of what was widely perceived to be a crisis in the education sector: “The idea that schools were in “crisis” first became conventional wisdom in the media in the late 1940s and continued throughout the 1950s” (22). As he points out, a large number of newspapers and magazines had taken to critiquing aspects of the nation’s public school system, including its outdated curricula, inadequate infrastructure, and underqualified teachers, along with a worrying surplus of unfilled positions and teachers with low morale (22).

Blackboard Jungle also communicates a cultural questioning of children’s value that accompanied the baby boom. This notion is perhaps most potently evoked by Richard Dadier’s as yet unborn child, carried by his wife, Anne (Anne Francis). Given a recent miscarriage, Anne and Richard are meticulously careful to avoid subjecting Anne to any undue stress. Ostensibly, Anne’s forever-endangered body evokes the preciousness and vulnerability of the child—their particular child and the figure of the child more generally. It also helps cements the villainy of problem child Artie, a gang youth who takes to phoning Anne anonymously in order to falsely inform her that her husband is having an affair, behavior that produces in her precisely the kind of mental unbalance that will endanger her child. However, in the context of a film about juvenile delinquency, Anne’s pregnancy also encourages us to speculate anxiously on how this precious child might actually turn out. Early in the film, Richard optimistically comments to Anne (and with sexism endorsed at the time) that their child will “have [her] looks and [his] brains and take care of us when we’re old.” Yet everything to which he bears witness suggests a rude contradiction to their hopes. So troublesome are the film’s teenagers, so pervasive is the delinquent subculture they inhabit, that one wonders at the risk involved in even having children. This connection between the delinquent youths and Dadier’s unborn child is further evoked by the students’ pet name for Dadier: “Daddy-O”—a name spat at him during his final showdown with the villainous Artie.

Brooks’s film also gestures with a subtle yet discernable venom to a postwar economy transformed by the employment of women, the kind of workforce change that, as we shall see, became acutely relevant to a number of horror films featuring child villains, from The Bad Seed to The Ring (2002). “Do I look alright?” opens Lois Hammond (Margaret Hayes), the elegantly dressed teacher beginning the term with Dadier. “Ravishing,” replies a colleague who speaks his every remark with a retiring cynicism. “They may even fight over you.” In her sexual advances on Dadier later in the film, not only does Lois inappropriately infuse the professional sphere with sexuality, but she almost compulsively illustrates her indifference for her job: “Tell me, Richard, don’t you ever get fed up with this place? Don’t you ever get tired of teaching; don’t you feel that you want to throw your briefcase away and take a flyer someplace?—anyplace? With me maybe … Don’t you? Don’t you, Rick?” Dadier’s refusal symbolizes not only his dedication to his wife and unborn child but also his thorough passion for teaching. To embrace this woman would be to embrace her defeatist, indifferent attitude to the problems the film depicts. Additionally, Lois’s indifference to her work insults the trials of a postwar economy in which male jobs are increasingly occupied by women (the start of the film shows Dadier waiting anxiously among a row of eager applicants).

The students’ delinquency is most powerfully illustrated by the attempted rape of Lois in the library after school. Having first flirted mildly with Dadier, to whom she offers a ride home, Lois proceeds down the staircase to wait for him to formally clock out. On the stairs, however, and with a self-conscious glance behind her, she surreptitiously raises her skirt and draws her stockings tighter. Not surreptitiously enough, however, to avoid the voyeuristic gaze of a student (Peter Miller) who lurks at the bottom of the staircase and who—speedily roused by this erotic display—drags her into the deserted library, where she will shortly after be rescued by her desired suitor. In Erving Goffman’s terms, Lois’s apparently backstage behavior in fixing her stocking has, with worrisome recklessness, been exhibited as front-stage behavior (indeed, a veritable exhibition) for the horny student who lurks in the extreme foreground (see The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life). At the moment Lois glances behind her in order to ensure that she is properly outside of Dadier’s hopefully admiring gaze, her attacker also pivots self-consciously, ensuring he is not under scrutiny. We can see, however, that situated over the railing, the attacker is hardly invisible from Lois’s perspective should she choose to actually look. In her preoccupation with her romantic life, this teacher is insufficiently mindful of her audience: a violent boy occupying the central foreground of the shot (just as he and his delinquent buddies should be foremost in any truly professional teacher’s awareness in this place). The student is expelled and incarcerated; however, the encounter is framed by a sexist culture that assumes to some extent Lois’s complicity in her own attack. The suggestion that Lois somehow asked for what she got is explicitly raised by Dadier’s jealous wife but implied more subtly by Lois’s preoccupation with her own appearance, carried on against all warnings (“they may even fight over you”), as well as by her continued intermingling of the romantic with the professional in her pursuit of Dadier.

Released the same year that i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Little Horrors: Introduction

- 1. Reaching the Age of Anxiety: The 1950s and the Horror of Youth

- 2. Spoiled Rotten: Horror’s Bourgeois Brats

- 3. A Scary Sight: The Looking Child

- 4. “The Hand That Rocks the Cradle”: The Child Villain’s Malignant Mom

- 5. Vicious Videos, Missing Mothers: The Ring

- 6. Little Bastards: Patriarchy’s Errant Offspring in It’s Alive and The Omen

- 7. Past Incarnations: The Exorcist and the Tyranny of Childhood

- 8. All Fun and Games till Someone Gets Hurt: Hating Children’s Culture

- 9. Too Close for Comfort: Child Villainy and Pedophilic Desire in Hard Candy and Orphan

- Afterword

- Notes

- Works Cited

- Index

- Back Cover