![]()

1

The Vessantara Jātaka as a Performative Text

The Vessantara Jātaka in Thailand is quintessentially a performative text. The story’s historical popularity and its impact on Thai political culture and social organization derive from the fact that the story was, from very early times, designed to be communicated in oral form in the vernacular to an audience. Were it not for the fact that the Vessantara Jātaka was disseminated in this way the story would never have achieved the popularity or influence it has, and would most likely have remained a little-known subject of erudite monastic scholarship.

Thet Maha Chat literally means “recitation of the Great Life.” The “Great Life” refers to the life of Prince Vessantara, the penultimate incarnation (chat, from the Pali jāti) of the bodhisatta, before his rebirth as the Buddha. Thet (or thetsana) can be translated variously as “recitation,” “sermon,” “preaching,” or more fully, “exposition of the dhamma,” that is, the religious doctrine contained in the Buddha’s teachings.

In trying to account for the Vessantara Jātaka’s popularity most scholarship tends to examine the story itself, separate from the medium by which the story was communicated. If we are to understand the way the story was received by audiences in premodern times it is essential to look at the story’s meaning in the context of the Thet Maha Chat, the ceremonial recitation through which the story became known to people. The performance of this ceremony imparted to the Vessantara Jātaka an aura of sanctity and authority that is entirely missing in, for example, modern paperback editions of the story, which contribute to the common interpretation of the Vessantara Jātaka today as a kind of folktale. The various components of the performance enhanced the authority of the story by repeatedly stressing the fact that it was based on the Buddha’s own utterances (Pali: Buddhavacana). This fact, signified in the recitation in diverse ways, had the effect of raising the story’s status to one of religious authority. To understand this process let us examine the various components of the Thet Maha Chat.

The Sacred Text

The text that is recited at the Thet Maha Chat ceremony has its origin in the Pali Jātaka Commentary (Pali: Jātakatthavaṇṇana, or Jātakaṭṭhakathā), believed to have been composed in its final form no later than the fifth century AD on the island of Sri Lanka. The Jātaka Commentary consists of 547 Jātakas (though often referred to as “five hundred and fifty”). The Vessantara Jātaka is the final story in the Jātaka series.1 The Vessantara Jātaka, as it appears in the Jātaka Commentary, comprises two distinct parts: the verses (khatha), which are held as having been actually uttered by the Buddha himself, and a prose commentary (atthakatha), traditionally attributed to the great fifth-century commentator of the Pali Buddhist tradition, Buddhaghosa. Although the Pali Jātaka Commentary has survived intact in Thailand it is not this version of the Vessantara Jātaka that is recited at the Thet Maha Chat ceremony, but vernacular translations that have been versified into Thai poetic meters.

For the wider communication of Buddhist teachings the Pali scriptures had to be translated into the vernacular.2 This at once created the risk that the translation would distort in some way the meaning of the original Pali text. The changes involved in translation were something monastic scholars were very much aware of. Vessantara Jātaka texts composed for recitation were careful to show deference to the changes the content had gone through in translation. Most vernacular recitation versions of the Vessantara Jātaka interspersed the translated text with the Pali words or phrases, known in Thai as chunniyabot, from the original Pali version of the Vessantara Jātaka.3 The oldest Thai version of the Vessantara Jātaka in existence, the Maha Chat Kham Luang, composed in the kingdom of Ayutthaya in the late fifteenth century and still recited today,4 went as far as including the entire Pali original—both commentary and verses—in the translation. The text was structured by placing a phrase in Pali followed by its translation, until the whole of the original has been translated.5 Not only did this guarantee the rendering of the Buddha’s actual words but it also provided the opportunity for those literate in Pali to check the accuracy of the translation. The drawback of this method of translation, however, was that the amount of Pali the recitation contained, which was unintelligible for the majority of listeners, detracted from the aesthetic appeal of the narrative. For a narrative that could take up to a day to recite in its entirety, that presented a problem. This explains the popularity of the versions of the Vessantara Jātaka written for recitation in the vernacular.6

Despite the fact that countless vernacular translations of the Vessantara Jātaka have been made throughout the Thai kingdom, they all shared the same basic narrative structure, since they were anchored by the original Pali version and the requirement that the words first uttered by the Buddha be accurately rendered in the vernacular.7 Thus, although communicated to an audience in oral form, the Vessantara Jātaka was in no sense an oral tradition, which is the case with most so-called folktales. There are no markedly variant versions of the Vessantara Jātaka as there are with stories based on oral tradition. On the contrary, the story’s form and transmission through successive generations were determined by textual factors, since it was the text which preserved the integrity of the Buddha’s words. Indeed, when comparing versions of Vessantara Jātaka texts from different regions of Thailand one is struck by their lack of divergence from the same basic narrative.

The Manuscript and Scripts

The Thet Maha Chat is a complex process of communication whose message is the words supposedly first uttered by the Buddha. For pre-print societies, the medium that conveyed that message to its audience was of considerable importance, worthy of the message it conveyed. In the case of the Thet Maha Chat, the medium consisted of two elements, the palm leaf manuscript, known in Thai as bai lan, and the script.

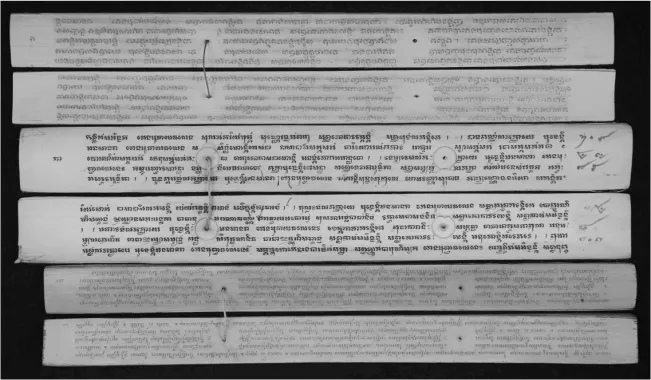

Figure 1.1. Bai lan manuscripts of the Vessantara Jātaka; picture courtesy of the National Library of Thailand.

In recitations of the Vessantara Jātaka monks would read from a bai lan manuscript. The bai lan is a strip of leaf from the corypha palm. The text of the bai lan consisted of inscriptions made onto the face of the palm leaf by means of a sharp stylus. The leaf would then be rubbed in ash, which is caught in the incisions and brushed off from the rest of the leaf face, leaving the inscribed text legible against the background of the leaf.8 Several leaves were tied together into bundles known as phuk, which together made up the complete text. Palm leaf manuscripts were the traditional means of preserving the Buddhist scriptures. In the Thai kingdom the corpus of Buddhist canonical scripture, the Tipiṭaka, was preserved in this way until 1893, when the Thai court published the scriptures for the first time in printed folio form.

The bai lan manuscript was a sacred object and treated with utmost respect. Today, in areas where older traditions survive, this is still the case. Before reciting its contents the monk will raise the manuscript above his head as a gesture of reverence. It is never held below the waist, and when transported it is placed on the carrier’s shoulder.9 In the procession to the place where it is to be recited the bai lan manuscript is carried ahead of the monk who will recite it—symbolic of the reciter’s subordination to the text.10 On the day of the Thet Maha Chat the bai lan containing the text to be recited is carried to the place of recital wrapped in expensive cloth (pha hor phra khamphi) and sometimes placed in a specially crafted box.11 At the place of recital, in some regions, there is a small stand (“khakrayia”) specially designed for the purpose of holding the bai lan before and after reading.12 In the recitation itself the bai lan is commonly held between thumb and forefinger, sometimes with the hands pressed together in the traditional attitude of respect. This is despite the fact that for monks experienced in recitations of the Vessantara Jātaka the text has already been memorized,13 which underlines the signifying function of the bai lan in the Thet Maha Chat ceremony. Even in the age of mass production of printed materials in book form on paper, the bai lan continues to be used in Thet Maha Chat ceremonies as the “medium” of the story of the Vessantara Jātaka. The only concession that has been made to modern technology is that the text is now usually printed onto the palm leaf by religious publishing houses instead of being incised by local scribes.14

The script inscribed or printed onto the palm leaf is another element in the process of communicating the Vessantara Jātaka. Today, most versions of the Vessantara Jātaka...