![]()

Part I

Indigenous Presence in the Silent Western

![]()

1

Reframing the Western Imaginary

James Young Deer, Lillian St. Cyr, and the “Squaw Man” Indian Dramas

In 1912 John Ford's older brother, Francis Ford, partnered with Thomas Ince, producer and director of early popular “Indian dramas,” to direct The Invaders, a three-reel film for Kay-Bee Pictures. The ambiguity of the film's title, which refers to white surveyors illegally trespassing on Lakota lands, draws our attention to competing stories about U.S. imperialism in the West in ways that other Westerns generally sought to camouflage. Later Indian dramas and silent Westerns, centrally concerned with legitimating white settlers' title to land through the manipulation of the Native characters' emotional and political allegiances, typically suppressed any acknowledgment of Indigenous land ownership by inverting history to figure Natives as the invaders of white settlements.1 The Invaders is unusual in that it addresses issues of tribal land rights by returning, insistently, to the text of a treaty no fewer than four times in the intertitles during its 40-minute length (see figure 1.1). Yet this struggle over territory is also conveyed through the visual and narrative conventions of the domestic melodrama, the customary mode for cinematic Indian dramas. These frontier melodramas articulate land ownership as a right of inheritance, yet envision the transfer of legitimate title to land-based resources through profoundly ambivalent representations mixed-race families.

The Invaders was part of a surge in productions of Indian dramas prior to World War I.2 These short films provide a remarkable window on Euro-American popular representations of the encounter between tribal peoples and the U.S. military and educational establishments. Their composite narratives depict a white settler “family on the land” emerging from the “broken home” of a previous mixed-race marriage, and equate children, land, and gold as the spoils of failed romance, not of war.3 The films—epitomized by Apfel and DeMille's 1914 production of The Squaw Man, the first feature-length film shot in Hollywood—represent a foundational paradigm in the formation of the Western Indian drama. These narratives of cross-racial romance and disruption of Native and mixed-race families, particularly scenarios of the separation and return of Native youth from their tribal homelands, would prove immensely influential in plotting future revisionist or “sympathetic” Westerns. Cinematic scenes in which Native and mixed-blood children are taken from their families drew moral and emotional power from their direct correlation with actual practices: the removal of children from Native homes in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to be educated in government boarding schools and the often coercive adoption of Native children by missionaries. This chapter traces the political implications of these films about interracial romance and biracial children—films influenced directly and indirectly by the stage play The Squaw Man—and the revisions to this story in films by Indigenous filmmakers and performers James Young Deer (Ho-Chunk) and Lillian St. Cyr (Ho-Chunk). I begin by examining the scene of romance in The Invaders, in which sexual attraction and the transformation of Native political allegiance coalesce around the technological mediation of interracial relations.

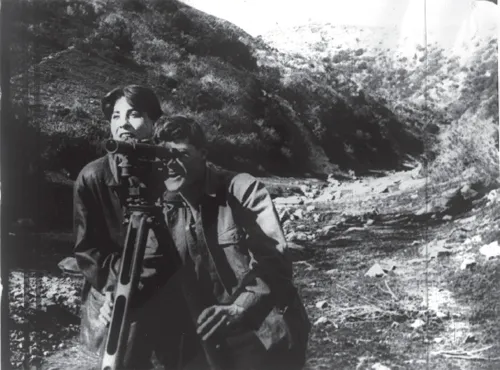

Early in The Invaders, the surveying team, having refused an Army escort, sets up camp in the hills and a young man begins to study the landscape through his moveable telescope (a transit or theodolite for surveying; see figure 1.2). Here the film's focus on land claims comes together with one of the most basic and enduring plots in the history of the movies: the young man meets a girl. The reverse-shot, an iris shot4 to mimic the telescope's viewing apparatus, does not reveal the expected open landscape; instead, the surveyor sees a young and beautiful Native woman leaning on a rock (Sky Star, played by Anne Little in redface). He calls his friends over to share the view and his excitement, and the land and woman come to stand for one another as objects of the technologically enhanced gaze of the white surveyors, the invaders of the film's title, whose economic interests lie in opening Native land to settlers through the railroad.5

The young surveyor is a likely figure of identification for audience members at this moment because we have been sutured to his point of view through the shot-reverse-shot construction and the long-shots so frequently used to represent the view through the gun sights of a repeating rifle in later Westerns. Yet this moment also resembles—and seems to represent—the act of filmmaking itself through the surveyor's manipulation of the telescope. The similarity of the equipment suggests an association between surveying equipment and the camera in an extension of the cinematic “gun/camera” trope.6 Here the action of the film correlates an imperialist gaze with Western settlement. The directorial and spectatorial aspects of viewing in this scene, in which the transit reflexively doubles as a movie camera, link the theatrical work of filming the West with the colonizing work of mapping land for railroad acquisition and resource extraction. These related ways of seeing converge in the act of constructing Indigeneity as a visual object of study and spectacle. Thus the scene suggests the ways that technologies of viewing instantiate as well as visualize imperial invasion and social rupture: filming is a form of claiming.

This mediated gaze as a form of knowledge-making is both desirous and possessive, a visual apprehension of the land that is a prelude to (and a metaphor for) claiming it. The relationship between looking and claiming has been theorized by Mary Louise Pratt, who argues that the colonizing gaze positions the gazer as a “monarch-of-all-I-survey” (201), and Anne McClintock has pointed to ways that visual gendering of Indigenous and settler women's bodies “served as the boundary markers of imperialism” (24). In The Invaders, land, gold, and women are conflated by the invasive viewing and mapping undertaken by the surveyors.

Figure 1.1. The Invaders, Kay-Bee (1912) (LC), Signing the treaty.

Figure 1.2. The Invaders, Kay-Bee (1912) (LC), Surveyors look through the viewscope.

Crucially, the gaze that maps both mineral-yielding land and the Native woman's body interrupts treaty rights and Native family formation at the same moment. Indeed, the two are intimately connected because treaty rights constitute promises that carry into the future, a future both symbolized and embodied by Indigenous families, especially children. The violence of conquest is allegorized in The Invaders as a process of cinematic or directorial vision, and Indigenous political ownership of land takes the visual form of a Native family (distilled here as the young woman's potential reproductivity). In the Western—and in its ur-genre the Indian drama—such prefigurations and images of families are especially freighted with discourses of national origins that negotiate social and political conditions in the historical moment of the film's production. The American West of the cinema, as a theatrical space that mediates societal forces beyond its proscenium, is a stage for social dramas in which families take shape through contestations over land. These politically charged issues of genealogy and staging in representations of Native families are the central focus of this chapter and those that follow.

Indian dramas were produced during a time when federal Indian policy encouraged both Indigenous assimilation and removal from the land. During the silent film era from the turn of the century through the 1920s, the primary national policy structuring Indigenous-settler relations was the drive for assimilation through the General Allotment Act of 1887 and the removal of Native children to government boarding schools. Sponsored by Senator Dawes of Massachusetts, the General Allotment Act (or Dawes Act) broke up reservations by allocating a specific acreage to each tribal member with the “surplus” land made available to “actual settlers.”7 As many scholars have noted, the boarding school and allotment systems went hand in hand, both reflecting the assimilationist impulse that held sway in Indian policy for 35 years. According to Margaret Szasz, “The passage of the Dawes Act …was the most significant legislative victory for assimilation, but the boarding school was one of its most effective weapons” (371). Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke) writes that “Government schools were responsible for preparing Indians for the independence envisioned by the Dawes Act” (3), explicitly linking the U.S. policies of separating children from their tribes (through institutional education) with assimilation (through individual land ownership). By the early 1930s more than 65% (90 million acres) of Indigenous land had been transferred to settler ownership under the allotment system (Dippie 308). Francis E. Leupp, Commissioner of Indian Affairs and a strong opponent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (the model for later government boarding schools), criticized the boarding school system in 1908 based on the schools' competition for students through a per-capita funding system. He also accused recruiters of engaging in a “regular system of traffic in … helpless little red people,” suggesting that “ownership” of Native children themselves was as much at issue as ownership of land.8 In 1900 there were 22,124 Native children reported attending government-run boarding schools (Bolt 227). The boarding school system emphasized separation from family and tribal groups; Native families were often very reluctant to send their children to boarding schools, particularly during the early phase of the policy. Resistance to the boarding school system was demonstrated also by the frequency of runaways and by parents hiding their children from government agents (an act depicted cinematically in Paramount's 1929 film Redskin, as I discuss in chapter 2).9

Most early Indian dramas capitalized on these powerful racial schema and federal policies to imagine the demise of Indigenous nations. Their versions of mixed-race families end with racial division or sacrificial death. Films that located Native characters in contemporary contexts often narrate failed assimilation as a measure of insurmountable racial primitivity. The ordeal of separating Indigenous children from their families and cultures through the government boarding school policy—and the trauma of their return home as outsiders—is recognized through melodramatic registers in silent Indian dramas. In these tales of interracial romance, captivity, and adoption, defining narrative features include doubling, mistaken identity, and the social and geographic displacement and re-placement of persons. Such narrative strategies formally replicate the physical acts of displacement and re-placement and of coercive assimilation that have been hallmarks of U.S. American Indian policy, from removal in the 1830s through the erosion of reservation lands in the twentieth century. Significantly, although scenarios of separation and return in the “squaw man” plot configuration clearly comment on the removal of children to boarding school and on the impacts of federal policies more broadly, the dramas take place exclusively in the realm of the familial. Indian dramas staged and encoded particular kinds of narratives about frontier family formation and succession through images of mixed-race couples, contested children, and familial disruption. The films translated racial and economic discourses of heritability to the screen using the emotional registers of melodrama in stories of child-swapping, costume exchange, and reorganized family structures.

Film scholar Linda Williams argues that American “melodramas of black and white” stage interracial sympathy by invoking the “nostalgia for a lost home” that is a central driving force in melodrama (58). Indian dramas similarly engage viewers in contemporary social problems by using “tears to cross racial boundaries” (55), dramatizing the suffering of the virtuous to establish “moral legibility” in a world that has become “hard to read” (19). The genre's theater of identity depended on costume in narratives featuring reconfigured families, conventions of coincidence, and emotional scenes of loss and recognition. That pictorial language of costume also informed images of Indians in a more evidentiary mode, one that powerfully influenced public policy—the before-and-after photographs of Native boarding school students. Thus underpinning the films' visualization of familial rupture and reunion were the visual documents supporting the actual institutional interventions in Native families taking place at the turn of the century in government boarding schools. These before-and-after photographs, as I have argued in the introduction, prefigured the mediated scenes of separation and return in Indian dramas, preparing the viewing public to “see” assimilation in the form of costume and to imagine actual children in institutional custody as figures for U.S. wardship over tribal nations. The combined power of realism and melodrama in images of Native familial separation depend, however, on the defining terms for white viewers' emotional engagement: the vanishing of noble primitivism in the face of imperial dispossession. Rendered in terms of pathos and action—what Williams calls the drama of “too late” and “in the nick of time” that characterizes melodrama—white sympathy in Indian dramas is with the “too late” of Indian vanishing rather than the “nick of time” that would instead recognize Indigenous political and familial continuity.

The racial uplift narratives implied by the Carlisle School before-and-after photographs, then, powerfully influenced the short films of the early 1900s and 1910s that were equally obsessed with costume, performance, and inherited identity. Indian dramas manifested converging discourses of Indian policy, tourism, and turn-of-the-century racial theories through a didactic combination of melodramatic and documentary modes, each dependent on costume as a visual key. The films integrated established conventions of racial portraiture in the before-and-after photographs of students with the emerging generic structures of the cinema Western, bringing together the visual racial coding of costuming with frontier melodramas' narratives of interracial violence and interracial sympathy. In doing so, the films established a visual lexicon of domestic mixed-race melodramas in which the semiotics of racial performance encoded political and territorial claims and counterclaims based on shifting identifications of Indigeneity.

Indian dramas, however, could also disturb photographic representations of cultural transition, revealing moments of trauma and resistance that are repressed in the more rigid still image sequencing of before-and-after photographs. Partly because of their expansive temporal fluidity compared with still images, the films frequently depict the very processes of separation and transformation concealed in before-and-after photographs. Just as often, they reverse the traditional image sequence in order to disassemble the signifiers of Euro-American assimilation. Like the tradition of ethnographic photography, Indian dramas could enforce a wider range of transformations than before-and-after photographs. The films' complex array of visual strategies and small variations in scenarios play with temporality and with the raced and gendered politics of civic allegiance, confronting viewers with questions of Indigenous political difference and social mobility in a contemporary framework—what Philip Deloria (Dakota) characterizes as “the problems o...