![]()

PART I

AFFECT AND EMOTION IN THE ERA OF BLACK LIVES MATTER

![]()

Chapter 1

Emotional Work and Care Labor in the Art and Politics of Black Lives Matter

BETH HINDERLITER

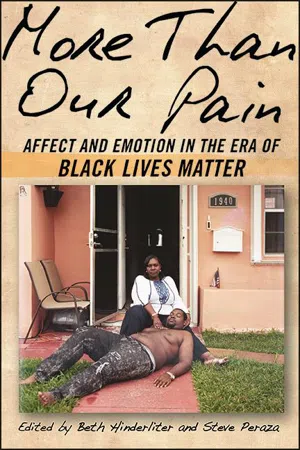

Poet Dominique Christina, grieving those slain in United States in 2017 by vigilante and police violence, laments, “I have forgotten how to cry in this country, I open my mouth, I capsize. I barely woman. I barely human. I wolf or something like it. I sugarcane and long memory. I cotton field and long blade. I eulogy. I suicide note. I manifesto. I rage. I grief. No tears left.” Her words pour forth emotions that exceed the confines of one body with its limited pool of tears. If 2017 were a poem, this is how it would feel. Rage and grief meet a love and joy that eulogize and seek to soothe this trauma. Christina’s words echo the sentiments of many Black Lives Matters activists who, in the years following 2013, made affect and emotion central to movement work, rather than the stuff of private lives to be dealt with solely inside the walls of one’s own home. “We are more than our pain,” DeRay McKesson tweeted during the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, where the streets were full of outpourings of grief, righteous rage, recognition of collective and individual hurts, but also the love and joy of shared fellowship. These emotions brought people together into the streets as the community sought to grapple with its pain. What emerged were new activist strategies seeking human rights that put emotion and emotionality at their core. As Yomaira Figueroa-Vásquez and Jessica Marie Johnson demand, “We need new words for what we do, for how and why we stay, for the labor of making black love and black joy and black pleasure in a world of this.”

Stressing the work of care as labor is one way to avoid naturalizing the relation of violence to suffering. The images of suffering bodies saturating our visual realm from the nightly news to visual arts museums and galleries obscure the violence of the perpetrator, often miring us in a spectacularized pain that fails to make the structural conditions of white supremacy and imperialist patriarchy visible. As detractors of the Black Lives Matter Global Network sought to dismiss its grievances and demands through distractive and race-baiting logic deployed in the media that conjured up stereotypes of black criminality, the gap between differing emotional worlds, or what Brittney Cooper has called sentient knowledges, became evident. To what extent are these knowledges shared or sharable under the current circumstances of racial capitalism that extracts value from this knowledge, while also debasing the conditions of life that gives rise to them? Important conversations around this have called for opacity to protect the vulnerable and for more work on how white supremacy codes specific white emotions and affects as universal, rational, and neutral. Erin Stephens, in particular, has focused on how Black Lives Matter organizers cultivated emotional resources for movement work specifically to mitigate the ability of “White emotion” to undermine legitimate grievances and claims of social injury. All too often in the years following the formation of the Black Lives Matter Global Network, both the dismissal and the co-optation, or colonization, of emotions have taken place requiring Black activists and movement leaders to continually reassert that black pain is not for profit. Within these conditions, co-conspirators to the antiracist work of BLM actors must address how their work does not amplify original violence, but dismantles structural injustices while sheltering those harmed from further exposure.

The embodied knowledge created during these moments has been central to the many artists, writers, and cultural producers who have turned to affect as a means to bring into focus those lives severed from political representation in the United States. Feelings are not psychological states beyond social meaning, as Sara Ahmed points out, but are social and cultural practices deeply related to the power structure of society. However, this view has been largely pushed aside in the mid–twentieth Century as the influence of B.F. Skinner’s behaviorism—and his view that emotions were only fictional causes of behavior—came to dominate many areas of thought. The supremacy and elitism dominant in academic spaces also impact movement work spaces as well, leaving many feeling that their emotions have been censored, controlled, or mediated in some way. For many BLM activists, the demands that rage and its many ancillary emotions be witnessed as righteous marked a clear break from the civil rights–era politics of respectability. If conservatives and reactionaries in the 1950s and 1960s identified civil rights activism with rage and rebellion rather than reason and reform, many Black leaders, in turn, trained activists to dress in Sunday clothes and turn the other cheek largely to counter these false narratives that painted protesters as thugs and criminals. However, the Black Lives Matter movement in the early twenty-first century makes no qualms about black rage and the prospects of rebellion. Collective rage, as Barbara Ransby reminds us in her book Making All Black Lives Matter: Reimagining Freedom in the 21st Century, can “simply be the refusal to tolerate the intolerable.” Black Lives Matter actors have simply demanded, “stop telling me how to feel” and are using these emotions to as a basis for their work.

How do we do the work of making structural violence visible when our emotions are erased or delegitimated? Consider, for example, how activists in the Black Lives Matter movement (and the artists inspired by them) have acted as affective geographers, mapping the spaces where we live our emotional lives in their fullest and also in their most diminished capacities. Signs by artist Kameelah Janan Rasheed placed in differing public spaces and galleries in 2015–2016 demand that viewers “lower the pitch of your suffering!” Invoking public responses to BLM activists’ complaints written off as impermissible by a larger public, her work reveals the nature of emotional labor brought forward by the Black Lives Matter movement. According to Rasheed, her work examines “superhuman restraint” in repressing anger. She reveals that in the face of state-sanctioned murder, barricades, handcuffs, and tear gas are not the only forms of discipline but, rather, smiles, tears, and anger. Our “compulsory affective labor of smiling through the pain,” Rasheed writes, “so as not to make others uncomfortable persists as a way to maintain social order.” As the mainstream media strove to delegitimize protestors’ rage, Black Lives Matter activists were constantly being told to manage their emotions, to turn away from the pain, and to smile. However, as bell hooks and others have pointed out, the suppression of feelings that arise from experiences of racism has many undesirable outcomes, including misdirected anger, self-destructive behavior, and a fear of intimacy.

Activists within BLM have stressed the need for self-care as emotions rage in us and as traumas tear us apart. In initiating a new conversation around the modes of self-care, BLM organizers and protestors reveal that care of the self is also care of the collective. That is, without intentional and intensive attention to care of the self, agents working against a logic of disposability and incarceration can often internalize and reproduce dominant white supremacist affects such as suspicion of the other or the need to attack or tear down illusory threats. As BLM co-founder Alicia Garza has commented, “our focus on care and caring for each other has to go beyond the way we talk about it—it’s very individual. It’s always like “take a day off.” It always involves capitalism … What we need to do to interrupt the logic of capitalism is invest in collective care, as much as self-care. And do a little bit of a deeper dive around healing trauma … we’re not as depthful as we could be around what it takes to address harm, and what we do to address trauma, and how we do that in a way where we don’t throw each other away but we build each other up.”

Self-care in the age of Black Lives Matter involves emotional care—individually and collectively. As AD Win, a social justice and public health advocate notes, “like many black children, I was told of the impending racism awaiting me in the world. Many of us are instructed to be resilient, dignified, and above all, strong. However, we are not taught that the assessment of our strength shouldn’t rest on a steely capacity to endure racism without emotional fallout.” However, caring for our emotional fallouts is often overlooked as what happens in our private lives, at home, away from movement spaces. We live in a white supremacist colonial cissexist ableist patriarchy that oppresses us in multiple ways, and the care labor that hold our communities together is so often overlooked, gendered as women’s work and erased. “Far too often,” Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha reminds us, “the emotional labor we do isn’t seen as labor—it’s seen as air, that little thing you do on the side. Not real organizing, not real work, just talking about feelings and buying groceries. Not a real activist holding a big meeting stuff.” BLM activists remind us that emotional healing is part of movement work: care labor cannot be erased and must be consensual so that everyone gets the care they need.

The framing of self and collective care initiated by Black Lives Matter has become a topic for artists and writers who extend activism beyond its traditional spaces into museum and gallery spaces and community spaces to develop new sensorial modes of engaging audiences. For example, artist Simone Leigh has elucidated the discourse of self-care and community care and the healing of trauma initiated by Black Lives Matter in her recent installations and art projects. Given the complex and important nature of her work and her involvement with the Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter group, I will explore her projects at greater length here.

In September to October 2014, Leigh established a Free People’s Medical Clinic, a performative and environmental art project that ran a month-long series of events, performances, and activities. Events at Leigh’s Clinic addressed medical discrimination and health disparities within historically black neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Part of a larger curatorial project titled “Black Radical Brooklyn,” Leigh’s work responded to curator Rashida Bumbray’s celebration of the Weeksville area in Brooklyn, a community founded by free Blacks ten years after emancipation in New York State—as an intentional place of refuge and Black power. Leigh’s contribution focused on the history of Black nurses within the community. Her installation was located at Stuyvesant Mansion, a house formerly owned by Dr. Josephine English, the first African American woman to establish an OB/GYN practice in New York state (who delivered all six of Malcolm X and Betty Shabazz’s daughters). The project also drew upon the legacy of the United Order of Tents, a group of Black nurses operating continuously since the era of the Underground Railroad, as well as the Black Panthers Party Free People’s Medical Clinics that fought against medical disparities in African American health care. During its month of existence, Leigh’s Free People’s Medical Clinic offered health and wellness classes and activities, including self-knowledge classes led by a master herbalist from the United Order of Tents, massage and acupuncture sessions, HIV screenings, wellness and OB-GYN care from Ancient Song Doula Services, as well as Black folk dance and a version of Pilates that Aimee Meredith Cox, an anthropologist and former dancer for Alvin Ailey’s dance troupe, calls afrocentering.

Administering to an audience partly from the surrounding community and partly from the art world, the Free People’s Medical Clinic drew on the historical legacies of black health care and healing while also responding to the contemporary moment within BLM activism, which has revealed the need for self and collective care to heal the trauma of police violence, including the trauma inflicted from watching videos of police violence. Leigh, who started a group of Black Women artists for Black Lives Matter, has in all of her work focused on the textures and concerns of black women’s lives and identities. For The Free People Medical Clinic, she targeted the long heritage of black nurses after being surprised to learn about the Order of the Tents, which owned and operated a care clinic out of a brownstone building in the Weeksville neighborhood.

“Black women,” Leigh remarks, “have been containers of this kind of knowledge [of care and healing] and have passed it down from one generation to the next.” Yet much of this knowledge, she finds, occurs in private spaces and doesn’t enter into larger public frameworks, leading not only to a threatened loss of this knowledge but a loss of its history altogether. This dynamic structured much of the participatory sessions in Leigh’s clinic: some classes and workshops, which otherwise would happen in a separate room, were brought out into the large open “waiting room,” which pulsed with the beat of house music provided by a resident DJ. On the other hand, certain sessions were closed events and offered only to specific visitors, such as a yoga class for South Asians and a workshop for those who identify as queer and/or transgender. “A lot of black life, for practical reasons, happened in secret,” Leigh has detailed. “If you can’t be completely human in public, maybe you can do that privately. It peeks out every now and then. But in these private rooms, a lot of culture is developed. All of this informs, I think, this project and the need, at times, for separatism.” Her strategies of opacity both resist any expropriation of labor while honoring the culture of dissemblance, which as Darlene Clark Hine reminds us, has been used by Black women to deflect the structural and interpersonal violence of white supremacy. Leigh’s focus on care as a critical mode in which to move through the world seeks to reduce trauma and its repetition, and therefore reject the politics of respectability, long criticized for its blaming of people as deficient, rather than dismissing the structures of oppression and power. In doing the emotional work around criticizing respectability politics, Black Lives Matter Global Network activists broke with an older generation of civil rights activists like Jesse Jackson and Al Sharpton—and their model of charismatic male leadership. From the exterior perspective, the movement felt leaderless by many who did not recognize anything beyond the framework of the older familiar styles of leaderships of the charismatic male. So much of how the BLM movement feels different from past freedom movement spaces is how the leadership of Black, Queer-centered, decolonial women are bringing their whole selves into these spaces in ways that simply were not legible before.

Self-care is another critical component here, as it recognizes how we must learn to walk through a world that is constantly impressing on us the infinite ways it can create immanent harm at any moment. It resists the older framework of empathy—that we are supposed to identify with or feel the pain of others, when so many from the movement have been trying to point out that this is itself a part of the problem of racism, this smothering presumption that emotions are visible/recognizable/accessible/transferable. E...