- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Future of the Citizen-Soldier Force by Jeffrey Jacobs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2021Print ISBN

9780813156217, 9780813118475eBook ISBN

97808131878531. THE THREE-ARMY SYSTEM

If American citizen armies, extemporized after the outbreak of war, could do as well as Washington’s Continentals and as well as the citizen armies of Grant and Lee, what might they not do if organized and trained in time of peace?

—John McAuley Palmer

THE defense policy of the United States is at a crucial crossroads. The Soviet Union, the threat for which the military has trained since World War II, has imploded. Domestic budgetary constraints, although they have always been an essential consideration in the formulation of defense policy, recently have assumed even greater importance. Given the changed threat and the reality of less money, defense policy makers face significant decisions concerning many issues—roles, missions, force structure, and procurement, to name but a few.

This book is about one of those issues: the future shape of the reserve components of the United States Army. Although B-2 bombers, M-1 tanks, and nuclear submarines may command larger headlines, the reserve issue is an important one that cannot be shunted aside as the course of the military is mapped out in Congress and the Pentagon.

Historically, the active Army has been a self-contained force that has required augmentation only in the event of a large-scale conflict requiring national mobilization, on the order of World Wars I and II. Until relatively recently, the role of the Army’s reserve components was to provide “forces in reserve”—a source of available manpower to supplement the active Army after it had reached the limit of its capabilities. The reserves generally were not ready to fight when called, and in some instances, volunteers and draftees played an equal or greater wartime role in expanding the Army.

Although the Vietnam War exceeded the capabilities of the peacetime active Army, the Army did not mobilize the reserves for that conflict but instead expanded with draftees. Dissatisfied with both the military and the political ramifications of the decision not to mobilize the reserves, the Department of Defense implemented the Total Force Policy in 1973. That policy, which governs the nation’s military reserves today, changed the role of the reserve components drastically.

The objective of the Total Force Policy is to integrate the services’ reserve components with their active components, obviating the necessity to resort to the draft. Under the policy, the Department of Defense has deliberately placed significant responsibility for the nation’s defense on the shoulders of the citizen-soldier; the reserves, rather than draftees, are now the nation’s primary source of available military manpower when expansion of the military beyond the size of the active force is required. The reserves, therefore, are no longer “forces in reserve” but a key cog in the United States’ military apparatus. In fact, the deployment of the reserves to the Persian Gulf for Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm was absolutely essential, because active forces could not have done the job alone.

As Desert Storm proved, the benefits of the Total Force Policy have been many. From the Total Army perspective, trained reserve units have provided the unit continuity so lacking during Vietnam. The policy also has put a strong military presence back into many civilian communities and has helped ensure that the employment of sizable American military forces will receive widespread political support. From the perspective of the Army’s reserve components, the Total Force Policy has infused the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve with money for equipment, training, facilities, and personnel.

Desert Storm, however, exposed some weaknesses in the Total Force Policy. And although Desert Storm answered many questions about the policy, it left many questions unanswered, and it raised many others. Does the policy work as advertised, or is the concept at least partially flawed?

The Total Force Policy has not lived up to expectations in many respects. The fundamental structure of the reserves has changed little since the 1920s.1 Superimposing the Total Force Policy on that structure in effect put a 1973 engine on a 1920 chassis. Moreover, because the Army as an institution has tended toward gradual evolution rather than more rapid change, the inertia of tradition has been difficult to overcome. The influence of this tradition, coupled with the fact that the Guard and Reserve have always been powerful political organizations (the Guard more so than the Reserve), has impeded a smooth transition from the rhetoric of the Total Force Policy into the reality of an effective Total Army, one in which all three of the Army’s components—the active Army, the Army National Guard, and the Army Reserve—are truly integrated.

The past few years have been ones of dramatic world change, and the world continues to evolve in ways that were inconceivable only a decade ago. As the threat changes and as the dollars dwindle, defense policy makers are examining the Army from top to bottom, and, consequently, the Army is changing significantly.

As major portions of the Army, the Army National Guard and the Army Reserve will not escape scrutiny. Indeed, change in the Army’s reserve components is inevitable. Just how the reserves will change, however, is a subject of some controversy. What should be the role of the reserves in the “new” Army? Should the Total Force Policy be retained as is, modified, or scrapped? What are the implications of Desert Storm vis-à-vis the reserves? If the reserves are forces unto themselves, if they do not fit smoothly into the wartime structure of the active Army, and if they are not as ready as they are expected to be, are they military liabilities in the context of a conflict on a scale broader than Desert Storm?

To those not familiar with the role of the armed forces in national policy, these questions may not seem to be of overriding national import. But they are. Historically, despite their best political efforts, the reserves have remained in the background of the public’s—and the Army’s—consciousness until the shooting starts. But as the Army inevitably shrinks, the importance of the citizen-soldier force will be magnified.

Although the Soviet threat may have disappeared, the United States will not become an isolationist nation, as it did after World War I. The world today is neither stable nor peaceful: witness the breakup of Yugoslavia, Middle East tensions, civil unrest in the Caribbean, and the proliferation of nuclear and chemical weapons. Even without the specter of the Soviets, threats to the United States’ interests persist throughout the world, as Desert Storm bore out. As General Colin L. Powell, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has written, “The real threat we now face is the threat of the unknown, the uncertain. The threat is instability and being unprepared to handle a crisis or war that no one predicted or expected.”2 Moreover, although the commonwealth that has replaced the Soviet Union is certainly not a foreseeable threat, given the current instability of that commonwealth and the fact that the former Soviet republics collectively still possess a significant nuclear capability and one of the largest armies in the world, the new commonwealth’s capabilities cannot be ignored completely.

As Desert Storm also proved, the active Army is not totally self-sufficient even against foes less formidable than the former Soviet Union. Indeed, the Army is now four active divisions smaller than it was in 1990 (and in 1995 it will be six active divisions smaller) and today could not fight Desert Storm without relying even more heavily on the reserves. In fact, the Army probably could not put a force of the same size and capability on the battlefield today without employing reserve infantry and armor units, which it did not use in Desert Storm. Therefore, as defense funding levels continue to decline and as long as the threat is that of the unknown, the post-Cold War active Army will be stretched to the limit, and the reserves may have to pick up even more of the slack.

The reserves’ increased importance thrusts the Total Force Policy directly into the national spotlight: the failure of the policy to achieve integration in fact as well as in theory could have significant implications on tomorrow’s battlefield. If the active Army cannot fight even brush-fire wars without the reserve components, the roles and capabilities of the reserves are indeed national defense policy issues of the first order. To ignore these issues is folly.

The tough questions, therefore, can no longer be ignored. Serious analysts of reserve issues have quietly asked most of these questions for some time. Policy makers, however, have swept them under the rug because of their political volatility. The nation deserves an informed debate on questions of such fundamental importance; at least then the risks of adopting (or continuing) policies that are less than ideal will be apparent and appreciated. The time has come to air these issues in the political arena.

To set the stage, an overview of the reserve components’ structure is in order (the Appendix contains more information for those not intimately familiar with the workings of the military or the Army). In practice if not policy, the Army is not one integrated service but three separate entities: the active Army, the Army National Guard, and the Army Reserve. Each of these components maintains its own separate bureaucracy, each is funded separately, and each has its own parochial interests.

To perform its mission, the Army is divided into one active component (the Regular Army) and two reserve components—the Army National Guard of the United States (an identity legally distinct from the Army National Guard, as explained later) and the United States Army Reserve. A reservist is a member of the reserve components, either the Army Reserve or the Army National Guard; a Reservist is a member of the U.S. Army Reserve. Although there are obvious similarities, each of these components is distinctive.

As of this writing, the combat power of the active component is concentrated in fourteen combat divisions.3 There are also forces independent of these fourteen divisions in the active component, ranging from armored cavalry regiments to corps support units to higher echelon combat service support units and, of course, the peacetime infrastructure necessary to administer and support such a force. (This is, of course, an oversimplification, but the purpose of this description is only to describe the active component sufficiently to understand its relation to the reserve components.)

Of the fourteen active divisions, only six consist wholly of subordinate active component units (although two more have a full active component complement and an “extra” reserve component brigade). Of those six, two are forward deployed, or stationed outside the United States, in Germany. The other four wholly active component divisions are contingency, or rapid-deployment, units—the 7th and 25th Infantry Divisions (Light), the 82d Airborne Division, and the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault).

The active component divisions are subordinate to one of four corps headquarters, which in turn are subordinate to one of the Army’s major commands. Units in Europe, for example, are commanded by U.S. Army Europe, those in the Pacific by US. Army Pacific. The corps and divisions in the continental United States are subordinate to U.S. Forces Command. The commander of Forces Command wears two hats, commanding most of the Army’s tactical forces in the continental United States as well as serving as the commander in chief of a specified command with the mission of defending the continental United States.4

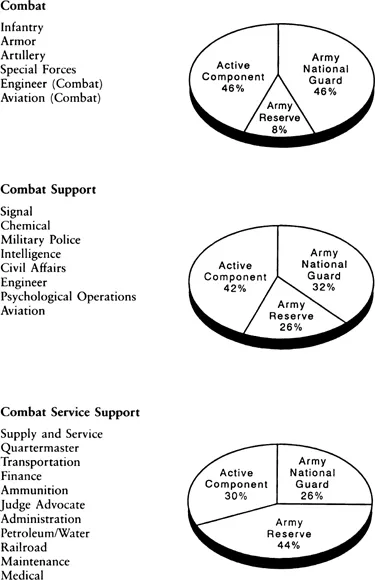

Source: 1990 Reserve Forces Policy Board Report.

Figure 1. Total Army Structure

Although the average citizen pictures only the active component when the Army is mentioned, the active component is, roughly, slightly less than half of the total Army. Under the Total Force Policy, the reserve components are now largely or wholly responsible for many important Army missions. As Operation Desert Storm proved, the Army, at least as it is configured in 1993, cannot perform its mission with active-duty soldiers alone (see fig. 1). Virtually every conceivable operational deployment of any significance will require the mobilization of at least some reserve component units and/or personnel. In fact, even actions as limited as the Grenada operation in 1983 and Operation Just Cause, the invasion of Panama in 1989, required the mobilization of reserve volunteers, despite the characterization of those operations as active component affairs. Indeed, by not mobilizing reserve units involuntarily for Just Cause, the Department of Defense contravened the wishes of the commander in chief of the U.S. Southern Command.

The reserve components are statutorily divided into three categories: the Ready Reserve, the Standby Reserve, and the Retired Reserve (see fig. 2). The Ready Reserve is the most readily mobilized and consists of reserve units and individual reservists not assigned to units. The Ready Reserve is further divided into the Selected Reserve, the Individual Ready Reserve, and the Inactive National Guard. The Selected Reserve consists of reserve units; full-time support personnel (discussed in greater detail below); and individual mobilization augmentees, who are individual Army Reservists assigned to augment active Army organizations, the Selective Service System...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- 1. The Three-Army System

- 2. The Evolution of Three Armies

- 3. Systemic Disconnects in the Total Army Circuit

- 4. Geography, Time, and Other Readiness Detractors

- 5. Lessons Learned from Desert Storm

- 6. Realizing the Potential of the Reserve Components

- 7. Through the Political Minefield

- Appendix

- Glossary

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index