eBook - ePub

Britannia's children

Reading colonialism through children's books and magazines

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Britannia's children by Kathryn A Castle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politique et relations internationales & Colonialisme et post-colonialisme. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

In S. R. Gardiner’s A Student’s History of England, first published in 1892, he wrote that it was his intention to explore ‘the peace and civilisation which it was the glory of British statesmen to introduce into India’.1 This statement, from one of the most influential historians of his age, cites the history of British India as the supreme example of the imperial ethos at work. Both junior and senior texts of his contemporaries felt obliged to describe with varying degrees of wonder, pride, and responsible scholarship how a small island nation had managed to gain control of vast territories and peoples, and export, with significant success, British values and institutions. This was the story which textbook authors agreed was an essential part of the education of a rising generation of imperial citizens.

Historians lived and worked within a society where popular lore and emotive memories had imbued events like the Indian Mutiny with associations they would have found difficult to deny. Added to this popular consensus was a concern that Britain’s future should rest upon an appreciation of its ‘glorious past’, making of Empire historians patriots as well as scholars. Against a backdrop of promoting the ‘wonderful development of the Anglo-Saxon race’ and ‘preserving that fabric from harm’, textbook historians approached British India as the primary example of imperial achievement. It was within these controlling imperatives that India entered the texts of school history.2

The image of India and its peoples emerged from what was included in the text and also through what was omitted, from general observations on the ‘condition’ of India and the assessment of individual figures, and finally through the comparisons which were inevitably drawn between English actions and character and those of the ‘other’. One of the most important considerations in the history textbooks’ treatment of British India was the selection of events chosen to illustrate the historical relationship between the two nations. Most writers conformed to a similar pattern of historical development, beginning with the establishment of the East India Company, moving to the struggle for supremacy with the French in the eighteenth century, emphasising the years of Mutiny, and finishing with the relative tranquillity of the post-Mutiny consolidation.3 Within this chronology, the student was encouraged to view India’s ‘history’ as commencing with its recognition by the Western world, a clear sign that inclusion was contingent upon the imperial connection. For example, discussion of the ‘state’ of India in the eighteenth century represented a context only for understanding the opportunities afforded for penetration by European powers. In 1899 George Carter’s description of the ‘Moghul Empire’ showed a characteristic attitude toward the relevance of indigenous Indian history:

It was a disordered state ... with an entire absence of anything like patriotism and unity, an easy prey to a foreign invader.4

India appeared in a state of anarchy and confusion, with a population ravaged by the constant warfare of constituent states, indeed hardly a nation at all by European standards. In the textbooks it was this disorder which both invited and justified the imposition of foreign control. Apart from offering the student the kind of background information which paved the way for the European presence, there were also some descriptive passages on the ‘races’ which inhabited the subcontinent, but here again the detail was directly linked to the evolution of British rule. Osmond Airy asserted that ‘our Empire in India had been possible because the inhabitants were not one race, but many races’. From the Anglo-Saxon perspective diversity was presented not as a rich cultural asset, but as a riot of competing linguistic and religious groupings without a unifying and stabilising core. Students must have felt their distance from ‘the Hindoos of 3,000 castes, with the worship of innumerable gods and endless diversity of ritual’.5

A concern with racial differentiation and hierarchies reflected the penetration of social Darwinism, as did the measuring of other races against the superior position of Anglo-Saxon characteristics. An historian might divide the Indian peoples into the non-Aryan, the Aryan invaders and the Hindu, describing them respectively as ‘flat nosed savages’, ‘a primitive civilisation’, and an uneasy ‘mixture’ of the other two.6 In 1912 Warner and Marten, borrowing an observation from Lord Curzon, offered a view on the diversity which was India.

The inhabitants of a vast continent speak 50 languages and vary in colour from the light brown of northern Pathan to the black of southern Tamil; and they are divided into races which, in the words of a recent viceroy, differ from one another ‘as much as an Esquimaux from a Spaniard or Irishman from Turk’.7

From this ‘vast mass of different elements’, they argued, a stationary civilisation had emerged, where no ‘cohesion or unity was possible’. Remarks such as these did little to encourage either tolerance or understanding of India and its peoples. Rather the country emerged as a strange and disordered community, clearly inferior to the progressive and dynamic integrity of the European model. Only occasionally in the junior readers can one find the older image of a ‘romantic’ India which had been held in the eighteenth and earlier nineteenth century. In ‘stories’ of Empire, rather than texts for the senior student, the ‘great and mysterious empire of India which has always exercised a fascination over men’s minds’ might still find expression.8 For the older pupil, reflecting the appropriate lessons for a potential servant of Empire, the ‘land of mystery’ gave way to the more pragmatic and immediate concerns of order, efficiency, and control. Difference now prompted stern ethnocentric judgements, and students encountered a derisory attitude toward practices of worship of ‘animals such as the cow, and the monkey, or anything unusual such as peculiarly shaped stones and trees’.9

India’s unstable society and the disorderly conduct of its population were underscored in the texts by the characterisation of those who resisted the European advance into their territory. While J. F. Bright offered a rather vague picture of the Mahrattas ‘dreaming of restoration of their national greatness’, the majority of historians agreed with S. R. Gardiner that they were no more than ‘freebooters on a large scale’ and an ‘imminent danger’ to British interests. J. M. D. and J. M. C. Meiklejohn in 1901 claimed that ‘they were disturbers of the peace of India, and had therefore to be put down’. Opponents of law and order, brought by the advance of British power, were generally treated with a summary justice in the histories. The Omans’ choice of words reflects this judgement on a people ‘finally crushed in 1817–18’. The ‘warlike clans’ of pre-imperial India became symbolic of the unregulated strife which had brought India into chaos, and were seen to bear a major responsibility for the intervention of external powers.10

Some respect was accorded to those pre-Mutiny rulers, however hostile, who represented a recognisable code of military or civil conduct. Haider Ali, Muslim ruler of Mysore in the eighteenth century, was one such figure. York-Powell and Tout provided an explanation for the textbook admiration of the ‘Master of Mysore’.

A tall, robust, strong, active man of fair and florid complexion, a bold horseman, a skilful swordsman and an unrivalled shot ... a Mohammedan, but tolerant and kindly to his Hindu neighbours ... the old soldier held his own until his death in 1782.11

Much like the Sikh leader, Ranjit Singh, ‘Lion of the Punjab’, Haider was respected as a formidable opponent, and presented as the exception in leaders of his era, one who recognised the need for religious conciliation rather than conflict. Also, crucially, the textbooks admired the fact that he appreciated the potential of British power, while his death removed the possibility of effective resistance. The description of this ‘enlightened despot’ was revealing for the standards which texts applied in judging the ‘good leader’. He was light-skinned, athletic, brave in battle, fair and tolerant, in fact, remarkably English.

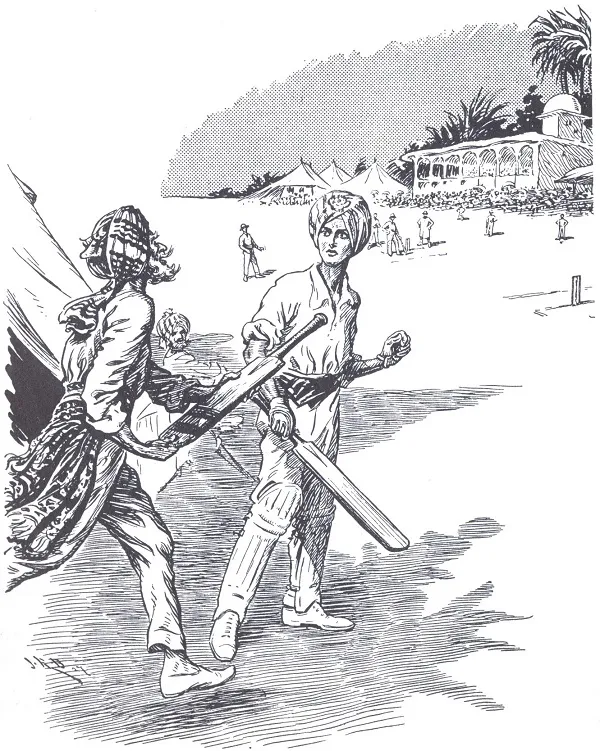

The Sikhs, despite opposing the British in two bitter wars of the nineteenth century, also earned admiration for their behaviour. The characterisation of their practices stands in contrast with dismissive attitudes toward other Indian peoples.

They were a religious sect who maintained the abolition of caste, the unity of the godhead, and purity of life, and were distinguished for the steadiness of their religious fervor.12

Warner and Marten, writing in 1912, found that the ‘steadiness and zeal’ of the Sikh could be compared to ‘Cromwell’s famous Ironsides’. This was one of the very rare instances in which any foreigners were accorded the status of shared characteristics with the British, and showed the unique position occupied by the Sikh in the history of British India. Part of this approval rested upon a ‘steadfast loyalty’ in the betrayals of 1857, the events which strongly influenced the negative image of Indian subjects. But part was also the clear line which had been drawn, as in the case of Haider Ali, between qualities accorded respect in the West, and those which represented a regressive and obstructive Indian leadership.13

For the student, however, despite the mention of worthy opponents in battle or the loyal Sikh, exceptions did not nullify the conclusion that a country in chaos needed the order and peace brought by British rule. S. R. Gardiner summed up what many of the textbooks suggested in surveying the ‘state of India’ on the eve of British expansion.

England cannot but perceive that many things are done by the natives of India which are in their nature hurtful, unjust, or even cruel, and they are naturally impatient to remove evils that are evident to them....14

That the Indian peoples were, according to the characterisation, exploited and static masses crushed by the greed and military ambitions of their leaders exemplified one such ‘evil’, and was commonly mentioned in the texts. This image was a strong underpinning of the students’ understanding of the case for British intervention, and stressed the need to move India closer to the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Front Matter

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- General editor’s introduction

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction to e-book edition

- Introduction

- 1 The untold millions: India in history textbooks

- 2 Princes and paupers: India in children’s periodicals

- 3 The unknown continent: Africa in history textbooks

- 4 The goodfellows: Africa in the children’s periodicals

- 5 The sleeping giant: China in history textbooks

- 6 The yellow peril: China in children’s periodicals

- 7 The inter-war years

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index