- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

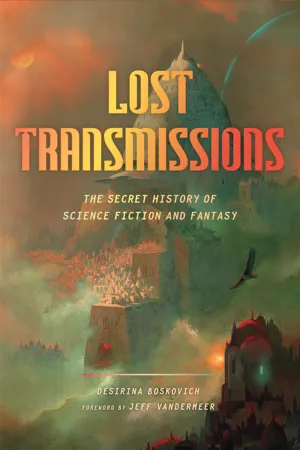

This illustrated journey through lost, overlooked, and uncompleted works is "a fascinating enrichment of the history of sf and fantasy" (

Booklist).

Science fiction and fantasy reign over popular culture now, associated in our mind with blockbuster movies and massive conventions. But there's much more to the story than the headline-making hits. Lost Transmissions is a rich trove of forgotten and unknown, imagined-but-never-finished, and under-appreciated-but-influential works from those imaginative genres, as well as little-known information about well-known properties. Divided into sections on Film & TV, Literature, Art, Music, Fashion, Architecture, and Pop Culture, the book examines:

Featuring more than 150 photos, this insightful volume will become the bible of science fiction and fantasy's most interesting and least-known chapters.

"Will broaden your horizons and turn you on to wonders bubbling under the mass-market commodified pleasures to which we all too often limit ourselves." — The Washington Post

Science fiction and fantasy reign over popular culture now, associated in our mind with blockbuster movies and massive conventions. But there's much more to the story than the headline-making hits. Lost Transmissions is a rich trove of forgotten and unknown, imagined-but-never-finished, and under-appreciated-but-influential works from those imaginative genres, as well as little-known information about well-known properties. Divided into sections on Film & TV, Literature, Art, Music, Fashion, Architecture, and Pop Culture, the book examines:

- Jules Verne's lost novel

- AfroFuturism and Space Disco

- E.T.'s scary beginnings

- William Gibson's never-filmed Aliens sequel

- Weezer's never-made space opera

- the 8,000-page metaphysical diary of Philip K. Dick, and more

Featuring more than 150 photos, this insightful volume will become the bible of science fiction and fantasy's most interesting and least-known chapters.

"Will broaden your horizons and turn you on to wonders bubbling under the mass-market commodified pleasures to which we all too often limit ourselves." — The Washington Post

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Lost Transmissions by Desirina Boskovich in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Film e video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Fiolxhilde summons a daemon from Lavania to transport herself and her son to the moon. Original illustration by Jeremy Zerfoss, 2018.

LITERATURE

We all know the famous story of how, in 1816, a nineteen-year-old girl named Mary Shelley invented science fiction. It was a gloomy and wet summer retreat at Lake Geneva. The party included Mary’s new husband, the philosopher and poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, along with their friend, famous Romantic poet Lord Byron. To amuse themselves, they began inventing ghost stories by the fire. Spurred by the dreary atmosphere, the stimulating conversation, and her vivid dreams, Shelley invented a modern twist on the classic ghost story—and a new genre was born. Frankenstein; Or, The Modern Prometheus was published in 1818.

But the story of science fiction hardly begins or ends there. Its seeds were planted in much earlier eras, in every culture’s mythological tales of supernatural beings and otherworldly planes. Its future was shaped by many creators and influencers who, intentionally or not-so-intentionally, gave the genre a push in one direction or another. Their contributions may not be so well-known, but they are no less worthy.

And then there are the forks in the road; the inflection points whose impact on the genre is only recognized much later. What if the weather had been fine that summer in 1816, and ghost stories were abandoned for pleasant days by the lake? Through secret history, we also explore these inflection points . . . and the stories that could have been.

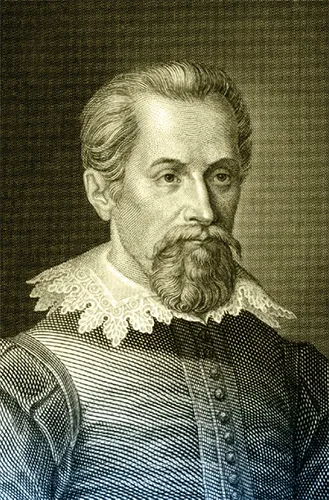

Kepler’s Proto–Science Fiction Manuscript Somnium and Its Legal Consequences

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) was a German mathematician and astronomer who played an essential role in the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century. He also wrote a work of proto–science fiction that landed his own mother in jail.

Kepler is known today for his laws of planetary motion, which set the stage for modern astronomy. He correctly proposed that planets travel in elliptical orbits (although he incorrectly imagined these orbits all occurred on the same plane). He was the first to explain that the gravitational pull of the Moon is what causes the ocean’s tides. He even coined the word satellite.

As a literal Renaissance Man, Kepler’s scientific contributions went well beyond astronomy. He’s also been called the founder of modern optics, as he developed significant theories of refraction and depth perception, and even the principle of eyeglasses.

He also wrote one of the earliest precursors of science fiction, lauded by visionaries such as Isaac Asimov and Carl Sagan. Somnium was written in Latin, as were most learned and scholarly works of the day; somnium means “the dream.”

This manuscript began as Kepler’s scholarly dissertation in 1593. But because of its controversial theories about the arrangement of the planets, his professors persuaded him not to publish it. In those days, insisting that the Sun was at the center of the solar system could land you in some serious trouble. Instead, Kepler continued to work on the manuscript sporadically for the next thirty-seven years.

At the core of the work is a description of what life would be like on the surface of the Moon. Of course, this was no idle flight of fancy; Kepler drew on his training as a scientist to envision the Moon’s climate, flora, and fauna based on the most advanced scientific knowledge of the day—knowledge that was still considered controversial by many.

This aspect of the story might well be considered hard sci-fi, drawing as it does on the era’s most accurate knowledge of natural science. But as Kepler continued to work with the manuscript, he cloaked the science fiction in myth and legend, adding the framing story of a dream and a fantastical journey to the heavens.

In 1976, science historian Gale E. Christianson wrote in the journal Science Fiction Studies: “There can be little, if any, doubt that Kepler selected the framework of the Dream to satisfy two major demands: First, fewer objections could be raised among the ranks of those still within the Aristotelian orbit by passing off this Copernican treatise as a figment of an idle slumberer’s uncontrollable imagination; and secondly, it enabled Kepler to introduce a mythical agent or power capable of transporting humans to the lunar surface.”

The dream framing begins to feel almost metafictional—perhaps Calvino-esque—in its layers of obfuscation. The story opens in first person, as Kepler writes that he was reading stories of the legends of Bohemia. Then he falls asleep and begins to dream. In his dream he reads a book. And within that book is the actual story, about a young boy named Duracotus.

One day, Duracotus makes the grievous error of angering his mother Fiolxhilde, who sells him to a ship captain. Duracotus gets seasick and the captain leaves him in the care of real-life astronomer Tycho Brahe, under whom Kepler himself studied for many years. Like Kepler, Duracotus becomes an astronomer and discovers the secrets of the celestial bodies.

After five years, Duracotus returns home to Fiolxhilde, who has regretted her impulsive child-selling and is pleased to have him back. He tells her what he’s learned about the skies. In turn, she reveals that she has her own knowledge of the heavens, imparted by spirits who can teleport her wherever she pleases. She calls on one of these daemons to transport the two of them to the Moon, aka the island of Lavania and home of the spirits. Soon after, the two of them are borne on the 50,000-mile journey to the Moon. (The Moon is actually considerably farther away than that, but not an awful guess on Kepler’s part, either.)

Here is where the text turns to science fiction. The rigors of the journey are described in detail. Once they arrive, Duracotus and his mother begin a detailed tour of the lunar satellite—where the extreme temperatures, low gravity, and rocky terrain suggest a very different world than our own. Kepler postulated that the extreme temperatures and low gravity on the Moon would produce totally foreign flora and fauna—for example, he imagined that creatures on the Moon would grow to massive sizes. He imagined that these large, snakelike creatures would spend much of their time roaming in the darkness, eluding the harsh, hot sun that in the unprotected atmosphere would quickly kill them.

Though now fundamental to science-fiction worldbuilding, at the time these ideas were positively groundbreaking. Christianson writes, “Nearly two centuries before Buffon, Lyell, and Darwin, Kepler had grasped the close interrelationship between life forms and their natural environment.”

Then the dreamer awakes, and the story is over.

Kepler began to pass around this manuscript-in-progress to some of his friends and colleagues. In 1611, one of these manuscript copies went missing, and began circulating among people who were less friendly to him. The autobiographical elements were obvious, so, it stood to reason that his real-life mother, Katharina Kepler, probably communed with spirits and demons. One humorous aside in Somnium consolidated the association, as Kepler wrote of the trip to the Moon: “The best adapted for the journey are dried-out old women, since from youth they are accustomed to riding goats at night, or pitchforks, or traveling the wide expanses of the earth in worn-out clothes.”

In 1615, Katharina was charged with practicing witchcraft. In further damning evidence against Katharina, her aunt had also been accused as a witch and burned at the stake; it was well-known that female pacts with the devil typically ran in families.

It was a tragic, and ironic, turn of events. Though the mythological aspects of the manuscript might have protected Kepler from the persecution of the Aristotelian astronomers, they exposed his mother to the machinations of the witchhunters.

Johannes Kepler was the first of many scientists to moonlight as a science-fiction writer. His research offered a scientific foundation for a speculative tale.

For the next five years, Kepler turned all his attention to clearing Katharina’s name. She spent fourteen months in jail. Finally, she was freed, but the stress of her imprisonment had taken a toll. She died soon after.

Guilt-stricken by it all and motivated to take a stand, Kepler decided it was time to finally complete Somnium. Between Katharina’s death in 1622 and 1630, he wrote 223 footnotes, which became the bulk of the text and expanded significantly on his scientific theories. In any case, the tides were turning and the Aristotelians didn’t hold the same power they once did. The scientific community was turning toward Copernican ideas such as Kepler’s.

Though he meant to publish Somnium, he did not have a chance. In 1630, he fell suddenly ill and died. In 1634, his son Ludwig Kepler published the work, less in honor of his father’s wishes and more from financial desperation—Kepler’s widow, Ludwig’s mother, was in dire financial straits.

As noted, Somnium was originally published in Latin. To this day, English translations remain limited, obscure, and difficult to obtain. Perhaps, in the twenty-first century, this oversight will finally be rectified.

How Jules Verne’s Worst Rejection Letter Shaped Science Fiction . . . for 150 Years

French writer Jules Verne (1828–1905) is known for his Voyages extraordinaires, novels that include the classics Around the World in Eighty Days, From the Earth to the Moon, and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. In fact, Verne penned more than sixty of these adventures, laying the groundwork for the highly imaginative narratives of more than a century to come. He has even been called “the father of science fiction.”

Verne’s novels have inspired many successful films and been translated into more than 140 languages. And his tales of bold exploration have fueled the fantasies and ambitions of real-life adventurers and record-breakers. The famous science-fiction author Ray Bradbury once wrote, “We are all, in one way or another, children of Jules Verne. His name never stops. At aerospace or NASA gatherings, Verne is the verb that moves us to space.”

So you can imagine the excitement of Verne aficionados, science-fiction fans, and lovers of French literature when in 1989, Verne’s great-grandson discovered the lost manuscript: Paris in the 20th Century, written 126 years before. The manuscript might never have been found if not for the youthful imagination of the younger Verne, who as a child had dreamed about the contents of a locked safe that had been in the family for generations, and the treasures it might contain. “Everyone thought it was empty, but in my imagination it was full of precious stones, gold, and fabulous jewels and strange objects given to or collected by my great-grandfather,” said Jean Jules-Verne.

As an adult, Jean Jules-Verne hired a locksmith to force open the old safe, revealing its contents. There were no jewels within. Instead, the safe contained Paris in the 20th Century, a never-before-published novel by the late, great Jules Verne. The book was published in France in 1994, and soon appeared in translation all around the world.

When manuscripts are discovered under such auspicious circumstances, it’s common to doubt their authenticity. However, this one was easily proven to be a Verne original. The paper, ink, and handwriting matched other Verne manuscripts. Notes from Verne’s editor, Pierre-Jules Hetzel, were scribbled in the margins, and that handwriting was also authenticated by experts. Most importantly, noted Verne scholar Piero Gondolo della Riva already possessed a letter written by Verne’s editor, rejecting the book in no uncertain terms.

Émile-Antoine Bayard’s illustrations for Jules Verne’s Around the Moon (1870) are some of the first to depict a technological approach to space travel.

Verne had already made a name for himself with the swashbuckling adventure stories that he’s still known for today, arming contemporary Industrial Age heroes with futuristic technology and pitting them against the terrors of nature. Paris in the 20th Century was a very different kind of book: a grim vision of the future, both philosophical and prophetic. Verne scholar Arthur B. Evans writes in Science Fiction Studies, “Despite its frequent (very Vernian) detailed descriptions of high-tech gadgetry and its occasional flashes of wit and humor, this dark and troubling tale paints a future world that is oppressive, unjust, and spiritually hollow. Instead of epic adventure, the reader encounters pathos and social satire.”

Verne’s editor was unimpressed. “I’m surprised at you,” Hetzel wrote. “I was hoping for something better. In this piece, there is not a single issue concerning the real future that is properly resolved, no critique that hasn’t already been made and remade before.” Hetzel called the manuscript “tabloidish,” “lackluster,” and “lifeless.” He told Verne that publishing the book would be a disaster for his reputation.

Apparently convinced by this litany of discouragement, Verne put the novel aside and returned to writing adventure stories. Instead of Paris in the 20th Century, Verne’s next published novel was Journey to the Center of the Earth, which remains popular with fans even today.

Édouard Riou illustration from Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (1863).

Nevertheless, when Paris in the 20th Century was finally published in the 1990s, contemporary audiences were fascinated by the opportunity to explore Verne’s vision of his future—which, as the book was set in the 1960s, now concerned a time long past. Many of Verne’s predictions of the modern age turned out to be shockingly on-point, both in his depiction of future technology and his vision of future social norms. Film archivist Brian Taves writes, “Virtually every page is crowded with evidence of Verne’s ability to forecast the science and life of the future, from feminism to the rise of illegitimate births, from email to burglar alarms, from the growth of suburbs to mass-produced higher education, including the dissolution of humanities departments.”

Though its prescience is striking, many readers agreed that as a work of fiction, the novel leaves something to be desired. The story follows a young poet whose talents are deemed worthless by a society that only cares about business and profit. While his misfortunes are distressing, they don’t quite coalesce into a co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Literature

- Film and Television

- Architecture

- Art and Design

- Music

- Fashion

- Fandom and Pop Culture

- Contributor Biographies

- Sources and Credits

- Index of Searchable Terms

- Acknowledgments