![]()

The Siege of Gloucester, 1643

With the end of the medieval period, Gloucester had entered something of a quiet phase. The city saw little change between the end of the Tudor period and the start of the seventeenth century. Gloucester was no longer a centre of Royal power; its economy had declined and it was something of a backwater.

That was until the autumn of 1643, when Gloucester became the stage for great events that changed the course of English history.

The English Civil War had been going on for nearly a year and, thus far, 1643 was going the King’s way. This time is known as the ‘Royalist Summer’, because the Royalist field army in the south-west had won victory after victory. The Royalists, having captured Bristol and defeated the Parliamentary field army at the battle of Roundway Down, needed only to take Gloucester before they could turn and march on London and perhaps win the war.

Charles I arrived at Gloucester on 10 August and demanded the surrender of the city. At 2 p.m., two royal heralds approached the city bearing a proclamation from the King. The garrison commander, Edward Massey,* allowed them to enter the city and the proclamation was read in the Tolsey (the town hall):

Edward Massey. (Credit Museum of Gloucester)

Out of our tender compassion to our city of Gloucester, and that it may not receive prejudice by our army, which we cannot prevent, if we be compelled to assault it; we are graciously pleased to let all the inhabitants of, and all other persons within that city, as well souldiers as others know; that if they shall immediately submit themselves and deliver this city to us, we are contented freely and absolutely to pardon every one of them, without exception; and doe assure them, on the word of a King …

(Gloucester and the Civil war: A City under Siege, Atkin, A. and Laughlin, W., 1992)

The proclamation offered pardon for all if they would surrender the city to the Royalists. Two hours was allowed for the answer.

Four hours later a response was sent:

We the inhabitants, magistrates, officers and souldiers within this garrision of Gloucester, unto his Majestie’s gracious message returne this humble answer, – That we doe keep this city according to our oathes and allegiance to and for the use of his Majesty and his royall posterity, and doe accordingly conceive ourselves wholly bound to obey the commands of his Majesty, signified by both Houses of Parliament, and we are resolved by God’s helpe to keepe this city accordingly.

(Gloucester and the Civil war: A City under Siege, Atkin, A. and Laughlin, W., 1992)

The council and garrison of Gloucester respond to the King. (Museum of Gloucester)

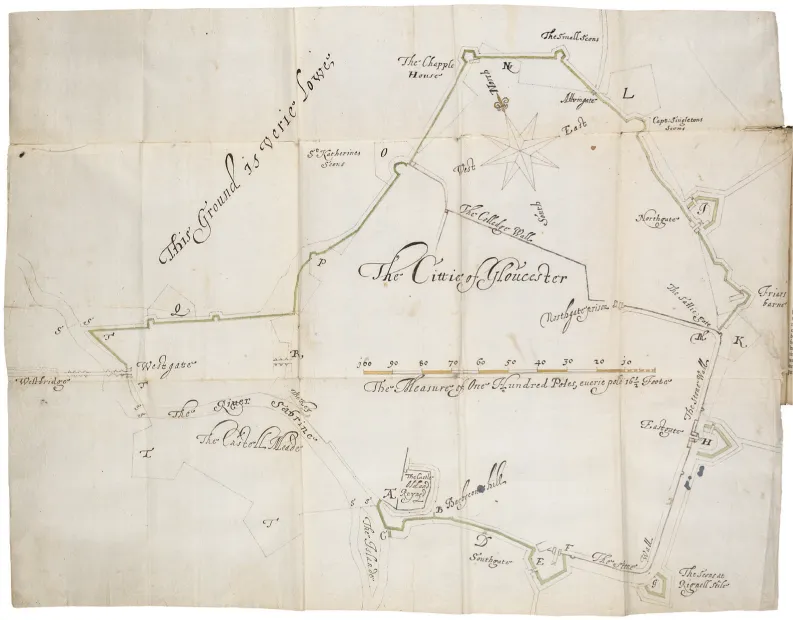

Gloucester during the siege of 1643. A simplified layout of the city produced for a newspaper feature about the city during the Civil War.

Which in short was a refusal to surrender, so the siege began. The drawing shows the defences of the city as they would have looked during the siege.

Until recently, any attempt to map the city’s defences during the siege has been rather confused. Thankfully, however, this map was discovered in 2012 in London and has since been purchased by the Gloucestershire Archives. It is hugely important as it shows the defences of Gloucester as built at some point between 1646 and 1653.* This is after the siege took place, but the map does show some key elements that are of interest.

Gloucester Castle (then a prison) is shown as being old and ruined. The Barbican Hill (the Old Castle motte) is shown adjacent. External earthwork bastions have been constructed outside the gates and we know that one was in place outside the south gate during the siege. What is striking is that much of the defences on the southern and eastern sides of the city relied on the old Roman and medieval walls. We know that both the east gate and the King’s Walk Bastion (see p.65) were standing during the siege and formed part of the front-line defences. The defenders constructed earth banks behind the walls to strengthen them and even filled houses next to the walls with soil to protect against artillery fire.

Plan of the Civil War city defences. (Permission Gloucestershire Archives Ref D12862)

The city’s Parliamentarian garrison during the siege included two infantry regiments; Stamford’s Foot (later Massey’s foot) raised in Essex, and Stephen’s Foot (also known as the Governor’s regiment and the ‘Bluecoats’) raised in Gloucester. These two drawings show soldiers of both Stamford’s Foot and the Gloucester Bluecoats. In total, the defenders probably numbered about 1,500 soldiers.

Soldiers of the Gloucester garrison.

The Royalist forces positioned a lot of their artillery to the south of the city around Llanthony Priory (see p.73) and in a field known as ‘Gaudy Green’, which is in the general area of modern-day Brunswick Square. These bombarded the city and the defences for many days and nights. The defenders located their cannon on Barbican Hill and the city walls and attempted to knock out the Royalist guns.

The Siege lasted from 10 August until 5 September. During that time, the people and soldiers of Gloucester were able to successfully defend against a Royalist army that may have numbered as many as 30,000. The city was eventually relieved by a Parliamentary field army, led by the Earl of Essex, which had marched from London.

Following the siege, the South Gate collapsed because of damage it had taken. When it was rebuilt in 1644, the following inscription was carved on the arch facing out of the city: ‘A city assaulted by man but saved by God’.

And on the inside ‘Ever remember the Fifth of September, 1643, give God the glory’.

Royalist cannon besieging Gloucester.

Until the restoration of Charles II, Gloucester celebrated the anniversary of the raising of the siege as a public holiday and this admirable tradition has since been re-established, with 5 September being celebrated as ‘Gloucester Day’. The City’s coat of arms today is based on that granted by the commonwealth in 1653 and shows a lion emerging from a walled crown holding a sword and a trowel, which represent the defence of the city’s walls. The motto is ‘FIDES INVICTA TRIUMPHAT’ – ‘Faith triumphs unconquered’.

So, did the siege matter? Well the defence of Gloucester did not win the war for Parliament, but it certainly stopped them losing. By delaying the Royalist forces for as long as they did, the garrison and people of Gloucester removed the best chance for a swift Royalist victory in 1643. The Royalists were never to see a high point like the summer of 1643 again and were to spend the rest of the war increasingly on the back foot. Indeed, one Parliamentary source referred to the people of Gloucester as the ‘conservators of the Parliament of England’.

The people of Gloucester were fighting for religious freedom, government by consent and the principle that all people, including kings, are subject to law. Their brave defence at Gloucester saved the Parliamentary cause from the very real chance of defeat, and the country from rule by a tyrant. So, with this in mind let us ever remember the 5th of September!

The city’s’ coat of arms.

________