![]()

Part I

![]()

The Pilgrim Whittles His Staff

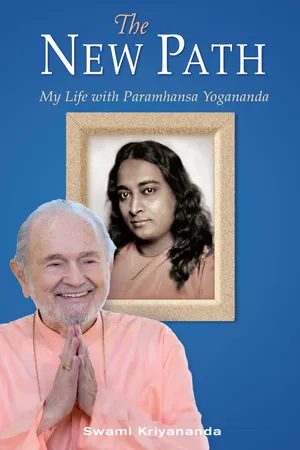

There are times when a human being, though perhaps not remarkable in himself, encounters some extraordinary person or event that infuses his life with great meaning. My own life was blessed with such an encounter more than sixty years ago, in 1948. Right here in America, of all lands the epitome of bustling efficiency, material progressiveness, and pragmatic “know-how,” I met a great, God-known master whose constant vision was of eternity. His name was Paramhansa Yogananda. He was from India, though it would be truer to say that his home was the whole world.

Had anyone suggested to me prior to that meeting that so much radiance, dynamic joy, unaffected humility, and love might be found in a single human being, I would have replied—though perhaps with a sigh of regret—that such perfection is not attainable by man. And had anyone suggested to me, further, that divine miracles have occurred in this scientific age, I would have laughed outright. For in those days, proud as I was in my intellectual, twentieth-century “wisdom,” I mocked even the miracles of the Bible.

No longer. I have seen things that made a mockery of mockery itself. I know now from personal experience that divine wonders do occur on earth. And I believe that the time is approaching when countless men and women will no more think of doubting God than they doubt the air they breathe. For God is not dead. It is man only who dies to all that is wonderful in life when he limits himself to worldly acquisitions and to advancing himself in worldly eyes, but overlooks those spiritual realities which are the foundation of all that he truly is.

Paramhansa Yogananda often spoke of America's high spiritual destiny. When first I heard him do so, I marveled. America? All that I knew of this country was its materialism, its competitive drive, its smug, “no-nonsense” attitude toward anything too subtle to be measured with scientific instruments. But in time that great teacher made me aware of another aspect, an undercurrent of divine yearning—not in our intellectuals, perhaps, our self-styled cultural representatives, but in the hearts of the common people. Americans' love of freedom, after all, began in the quest, centuries ago, for religious freedom. Their historic emphasis on equality and on voluntary cooperation with one another reflects principles that are taught in the Bible. Americans' pioneering spirit is rooted in these principles. And when no frontiers remained to our people on the North American continent, and they began exporting their pioneering energies abroad, again it was the spirit of freedom and willing cooperation that they carried with them, setting a new example for mankind everywhere. In these twin principles Paramhansa Yogananda saw the key to mankind's next upward step in evolution.

The vision of the future he presented to us was of a state of world brotherhood in which all men would live together in harmony and freedom. As a step toward this universal fulfillment, he urged those people who were free to do so to band together into what he called “world brotherhood colonies”: little, spiritual communities where people, living and working together with others of like mind, would develop an awareness of the true kinship of all men as sons and daughters of the same, one God.

It has been my own lot to found the first such “world brotherhood colonies,” examples of what Yogananda predicted would someday become thousands of such communities the world over.

Because the pioneering spirit is rooted in principles that are essentially spiritual—implying the perennial quest for a higher as well as a better way of life—that spirit has not only expanded men's frontiers outwardly: in recent decades, especially, it has begun to interiorize them, to expand the inward boundaries of human consciousness, and to awaken in people the desire to harmonize their lives with truth, and with God.

It was to the divine aspirations of these pioneers of the spirit that Paramhansa Yogananda was responding by coming to America. Americans, he said, were ready to learn meditation and God-communion through the practice of the ancient science of yoga. It was in the capacity of one of modern India's greatest exponents of yoga that he was sent by his great teachers to the West.

In my own life and heritage, the pioneering spirit in all its stages of manifestation has played an important role. Numerous ancestors on both sides of my family were pioneers of the traditional sort, many of them ministers of the Gospel, and frontier doctors. My paternal grandparents joined the great land rush that opened up the Oklahoma Territory in 1889. Other ancestors played less exploratory, but nonetheless active, roles in the great adventure of America's development. Mary Todd, the wife of Abraham Lincoln, was a relative of mine. So also was Robert E. Lee, Lincoln's adversary in the Civil War. It pleases me thus to be linked with both sides of that divisive conflict, for my own lifelong inclination has been to reconcile contradictions—to seek, as India's philosophy puts it, “unity in diversity.”

My father, Ray P. Walters, was born too late to be a pioneer in the earlier sense. A pioneer nevertheless at heart, he joined the new wave of international expansion and cooperation, working for Esso as an oil geologist in foreign lands. My mother, Gertrude G. Walters, was a part of this new wave also: After graduating from college, she went on to study the violin in Paris. Both my parents were born in Oklahoma; it was in Paris, however, that they met. After their wedding, Dad was assigned to the oil fields of Rumania, where they settled in Teleajen, a small Anglo-American colony about three kilometers east of the city of Ploe¸sti. Teleajen was the scene of my own squalling entrance onto the stage of life.

My body, typically of the American “melting pot,” is the product of a blend of several countries: England, Wales, Scotland, Ireland, Holland, France, and Germany. It was little Wales, the smallest of these seven, that gave me my surname, Walters. For Kriyananda is a monastic appellation that I acquired only in 1955, when I was initiated into the ancient Swami order of India.

The human body, through the process of birth, is a new creation. Not so the soul. I came into this world, I believe, already fully myself. I chose this particular family because I found it harmonious to my own nature, and felt that these were the parents who would best afford me the opportunities I needed for my own spiritual development. Grateful as I am to my parents for taking me in, a stranger, I feel less indebted to them for making me what I am. I have described them, their forebears, and the country from which they came to show the trends with which I chose to affiliate, for whatever good I might be able to accomplish for myself, and—I hoped—for others.

Everyone in this world is a pilgrim. He comes alone, treads his chosen path for a time, then leaves once more solitarily. His is a sacred destination, always dimly suspected, though usually not consciously known. Whether deliberately or by blind instinct, directly or indirectly, what all men are truly seeking is Joy—Joy infinite, Joy eternal, Joy divine.

Most of us, alas, wander about in this world like pilgrims without a map. We imagine Joy's shrine to be wherever money is worshiped, or power, or fame, or good times. It is only after very distant roaming that, disappointed at last, we pause in silent self-appraisal. And then we discover, perhaps with a shock, that our goal was never distant from us at all—indeed, never any farther away than our own selves!

This path we walk has no fixed dimensions. It is either long or short, depending only on the purity of our intentions. It is the path Jesus described when he said, “The kingdom of God cometh not with observation: Neither shall they say, Lo here! or, lo there! for, behold, the kingdom of God is within you.” Walking this path, we yet walk it not, for the goal, being inward, is ours already. We have only to claim it as our own.

The principal purpose of this book is to help you, the reader, to make good that claim. I hope in these pages to help you to avoid, among other things, a few of the mistakes I myself have made in my own search. For a person's failures may sometimes be as instructive as his successes.

I was born in Teleajen on May 19, 1926, at approximately seven in the morning. James Donald Walters is the full name I received at christening in the little Anglican church in Ploe¸sti. Owing to a plethora of Jameses in the community, I was always known by my second name, Donald, in which I was the namesake of a step-uncle, Donald Quarles, who later served as Secretary of the Air Force under President Eisenhower. James, too, was a family name, being the name of my maternal grandfather. It was my ultimate destiny, however, to renounce such family identities altogether in favor of a higher and more spiritual one.

Mother told me that throughout her pregnancy she was filled inwardly with joy. “Lord,” she prayed repeatedly, “this first child I give to Thee.”

Her blessing may not have borne fruit as early as she had hoped. But bear fruit it did, gradually—one might almost say, relentlessly—over the years.

For mine is the story of one who did his best to live without God, but who—thank God—failed in the attempt.

My parents, Ray and Gertrude Walters, in Teleajen, Rumania, a few days after my appearance on the scene, May 1926.

My mother, my brothers Dick and Bob, and I (right). If Dick was one year old at the time, I was five.

![]()

He Sets Out from Home

Joy has always been my first love. I have longed to share it with others.

My clearest early memories all relate to a special kind of happiness, one that seemed to have little to do with the things around me, that at best was only reflected in them. A lingering impression is one of wonder to be in this world at all. What was I doing here? Intuitively I felt that there must be some higher reality—another world, perhaps, radiant, beautiful, harmonious, in relation to which this earthly plane represented mere exile. Beautiful sounds and colors thrilled me almost to ecstasy. Sometimes I would cover a table down to the floor with a colorful American Indian blanket, then crawl inside and fairly drink in the luminous colors. At other times, gazing into the prism formed by the broad edge of a mirror on my mother's dressing table, I would imagine myself living in a world of rainbow-colored lights. Often also, at night, I would see myself absorbed in a radiant inner light, and my consciousness would expand beyond the limits of my body.

“You were eager for knowledge,” Mother told me, “not a little willful, but keenly sympathetic to the misfortunes of others.” Smiling playfully, she added, “I used to read children's books to you. If the hero was in trouble, I would point pityingly to his picture. When I did so, your lips quivered. ‘Poor this!' you exclaimed.” Mother (naughty this!) found my response so amusing that she sometimes played on it by pointing tragically to the cheerful pictures as well—a miserable ploy which, she informs me, invariably succeeded.

As I grew older, my inner joy spilled over into an intense enthusiasm for life. Teleajen gave us many opportunities to be creative in our play. We were far removed from the modern world of frequent movies, circuses, and other contrived amusements. Television was, of course, unknown at that time even in America. As a community composed mostly of English and American families, we were remote even from the mainstream of Rumanian culture. Our parents taught us a few standard Anglo-American games, but for the most part we invented our own.

Our backyard became transformed into adventure lands. A long stepladder laid sideways on the snow became an airplane soaring us to warmer climes. A large apple tree with hanging branches served a variety of useful functions: a schoolhouse, a sea-going schooner, a castle. Furniture piled high in various ways in the nursery would become a Spanish galleon, or a mountain fortress. We blazed secret trails through a nearby cornfield to a cache of buried treasure, or to a point of safety from the pursuing officers of some unspeakably wicked tyrant. In winter, skating on a tennis court that had been flooded to make an ice rink, we gazed below us into the frozen depths and imagined ourselves moving freely in another dimension of wonderful shapes and colors.

I remember a ship, too, that I set out to build, fully intending to sail it on Lake Snagov. I got as far as nailing a few old boards together in nondescript imitation of a deck. In imagination, however, as I lay in bed at night and contemplated the job, I was already sailing my schooner on the high seas.

Leadership came naturally to me, though I was unwilling to exert it if others didn't spontaneously share my interests. The children in Teleajen did share them, and enthusiastically embraced my ideas. More and more, however, as I grew older, I discovered that many people considered my view of things somewhat peculiar.

I noticed it first in some of the newly arrived children in Teleajen. Accustomed as they were to the standard childhood games of England and America, they would look puzzled at my proposals for more imaginative entertainment—like the time we gazed into unfamiliar dimensions in the ice while skating over it. Unwilling to impose my interests on them, I was equally unwilling to accept their imposition in return. I was, I suppose, eccentric, not from any conscious desire or intent, but from a certain inability to attune myself to others' norms. What was important to me seemed to them unimportant, whereas, frequently, what they considered important seemed to me incomprehensible.

Miss Barbara Henson (later, Mrs. Elsdale), our governess for a time, described me years later in a letter the way she remembered me as a child of seven: “You were certainly ‘different,' Don—‘in the family but not of it.' I was always conscious that you had a mystic quality which set you apart, and others were aware of it, too. You were always the observer, with an extraordinarily straight look in those blue-grey eyes which made you, in a sense, ageless. And in a quiet, disconcerting way, you made funny little experiments on other people as if to satisfy your suspicions about something concerning them. Never to be put off by prevarication or half-truths, you were, one felt, seeking the truth behind everything.”

Mildred Perrot, the wife of our Anglican minister in Ploe¸sti at the time, once told me, “I can go through a keyhole.”

“You can?” I exclaimed. From then on I kept pestering her to perform this miracle, until finally she relented. Writing the letter i on a small piece of paper, she folded it up and shoved it through a keyhole! I still remember my disappointment, for I wanted miracles to belong in the realm of the possible.

Cora Brazier, our next-door neighbor, a kind, sympathetic Rumanian lady, once remarked to Miss Henson, “I always try to be especially nice to Don, because he's not like the others. I believe he knows this, and is lonely.”

Although this knowledge was not to dawn on me fully until after I left Teleajen, there was even then a certain sense of being alone. It was held in abeyance, however, by the presence of good friends, and by a harmonious home life.

My parents loved us children deeply. Their love for each other, too, was exemplary and a strong source of emotional security for us. Never in my life did I know them to quarrel, or to have even the slightest falling out.

My father was especially wonderful with children. Rather reserved by nature, he yet possessed a simple kindness and a sense of humo...