- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

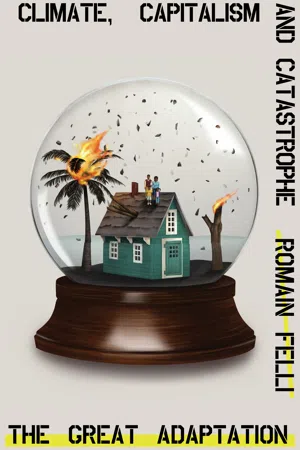

The Great Adaptation tells the story of how scientists, governments and corporations have tried to deal with the challenge that climate change poses to capitalism by promoting adaptation to the consequences of climate change, rather than combating its causes. From the 1970s neoliberal economists and ideologues have used climate change as an argument for creating more "flexibility" in society, that is for promoting more market-based solutions to environmental and social questions. The book unveils the political economy of this potent movement, whereby some powerful actors are thriving in the face of dangerous climate change and may even make a profit out of it

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Great Adaptation by Romain Felli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Political Economy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Climate Crisis and Capitalism’s Survival

At the beginning of the 1970s, the intellectuals, scientists and politicians pondering the future of Western societies – and especially the United States – were obsessed by the question of survival. The crisis of morale provoked by the war in Vietnam as well as the spread of social conflicts raised doubts about the future of the ‘free enterprise system’. Their fears over capitalism’s survival crossed paths with fears over the survival of the planet itself. Environmentalist sentiments were, at that time, expressed in a catastrophist form which used both a Biblical imagery – metaphors like the Flood, the Apocalypse or Genesis – and a vision of human society reduced to its biological dimension. For the science historian Jacob Hamblin, ‘Much of what is today considered pro-environment literature, in the 1960s and 1970s, was in fact human survival literature’.1

We would struggle to imagine the level of vulnerability that these intellectuals attributed to capitalism at the turn of the 1960s and 1970s. For them, this mode of production’s very survival was at stake, especially in the United States. This context shaped the way in which the environmental crisis was to be handled, indeed at a global scale. A growing part of the population challenged the existing order, organised to win new rights and no longer recognised the state or the economic system as having moral authority. The Civil Rights struggles in the United States, the feminist, workers’ and anti-racist movements, and the decolonisation struggles waged by the peoples of the Third World mutually reinforced one another. The USSR could still appear to some as a viable counter-model, especially after the end of the Stalinist period. In 1975, Time magazine ran the cover title ‘Can Capitalism Survive?’2 Conservative theorists like Ralf Dahrendorf and Raymond Aron worried over the disenchantment with progress. And Jürgen Habermas spoke of a legitimation crisis for capitalism.3

NEO-MALTHUSIANISM AND POLITICAL CONSERVATISM

The first Earth Day was organised in the United States on 22 April 1970. It brought apocalyptic worries over the state of the planet and the exhaustion of natural resources together with the critique of consumer society.4 Above all, it legitimised the idea that environmental problems are, above all, problems of human overpopulation, relative to the resources available and the planet’s own limits.

This horror at the overpopulation of the world has been common among many environmentalists, students of ecology and biologists, but also economists, politicians and activists who have discussed the environment since the end of the Second World War.5 Whatever their background or the particular focus of their interests, the US environmentalists of the 1940s and 1950s, from Fairfield Osborne to William Vogt passing via Aldo Leopold, lamented natural systems’ limited ‘load capacity’. They worried over the growing pressure to which ‘man’ was subjecting these systems on account of growing populations and rising consumption.

This Malthusian-environmentalist moment in the years between 1946 and 1975 crossed paths with another moment in the domain of economics. This second moment gripped the United States as it sought to manage a world on the road to decolonisation. Peoples’ struggles for their national independence transformed the relations between core and periphery. As the independent countries asserted their sovereignty over natural resources, the metropoles’ access to these goods – hitherto guaranteed by the colonial system – was no longer certain. The US superpower was, therefore, pressured to secure its long-term control over its supply lines and to promote the global expansion of US firms. It was at the same time confronted with mounting Soviet influence among the peoples seeking to liberate themselves. One response to these new constraints took the form of vast projects that sought to combat hunger and poverty in the so-called ‘underdeveloped’ world. On 20 January 1949, the fourth point in President Truman’s inauguration speech thus affi rmed the USA’s intent to help poor countries to ‘develop’.6

Nonetheless, as far as elites in the capitalist world were concerned, there was no question of recognising that poverty might be the result of colonialism and exploitation. As in the times of Reverend Malthus, the biologisation of the social would serve as a substitute for political economy. If the poor were poor, the main reason was that there were too many of them. The poor were producing too many offspring relative to the resources available to them, and thus entrenching themselves in poverty. Overpopulation provided a convenient explanation for an unjust situation. But it also represented a threat, for it was creating masses of poor people, hungry and radicalised, ready to come and break down the doors of the Empire.

Picking up on the neo-Malthusian vulgate, texts produced by the US Army warned against the effects of overpopulation. The report by the RAND Corporation’s Theodore von Karman drawn up for the US Air Force at the National Academy of Sciences in 1958 warned against the global rise of ‘non-whites.’ Von Karman detailed the prospect of coming famines as well as the vulnerabilities of the US owing to its growing dependence on complex systems.7

The grammar of overpopulation continued to give form to naturalists’ discourse throughout the 1970s and up till the mid 1980s. Biologists like Paul Ehrlich and Garett Hardin, the climatologist and oceanographer Roger Revelle and the physicist James Lovelock counted among the popularisers of this mode of thinking, notwithstanding their sometimes very different political perspectives. Th e historian Thomas Robertson defends the ‘Malthusian environmentalists’ (preoccupied with the pressures that population growth would place on the environment) from the worst accusations of racism, sexism and colonialism levelled against them. According to Robertson, the critique of economic growth had animated these writers just as much as the critique of overpopulation – and it blinded them to the political consequences of their theories.8

Until the 1970s, in North America environmental protection was a politically conservative endeavour. The creation of natural parks and the preservation of a supposedly intact nature were central to the construction of the American nation. They made up part of the violent dispossession of the native populations’ lands. Th e landscapes which Europeans saw as ‘untamed’ or ‘virgin’ territories (metaphors well expressing a patriarchal viewpoint) were in reality the product of a long-term ecological interaction between the original inhabitants and their environment.9 Much more than that, the conservation of nature as a resource was an important political project promoted by conservative Republicans from the 1900s (Th eodore Roosevelt) through the creation of the Resources for the Future (RFF) think-tank in the 1950s.10 The best stewardship of natural capital would allow production to draw on natural resources into the long term. In the 1960s and 1970s the potential exhaustion of natural resources again haunted conservatives, for example, a young Texan businessman from a wealthy East Coast patrician family, George H.W. Bush. Entering politics in 1969 he became the president of Young Republicans for the Environment. He fought for limits on birth rates in order to preserve natural resources: as he saw it, this was ‘the most critical problem facing the world in the remainder of this century’.11

AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION AND FAMINE

Neo-Malthusians constantly have to defend themselves from four accusations: of being racist, of being imperialist, of masking social inequalities and of making catastrophic predictions which never come to pass. These accusations are sometimes unfair. But one can pardon the accusers if the source of their allegations is the 1967 bestseller by the Paddock brothers. Agronomist William and US diplomat Paul combined their efforts in this short book, which would be a source of inspiration for the biologist Paul Ehrlich and the climatologist Stephen Schneider. Its title? Famine, 1975! America’s Decision: Who Will Survive?12

Having built up a dataset, the Paddock brothers predicted that the following years would see peak growth in global population and a drastic fall in agricultural production. They argued that global famine was inevitable by 1975 at the latest, but probably before that. Cuba, China and the USSR were, they claimed, already on the brink of collapse. Europe wasn’t in good shape either, not to mention India or Africa. Th e recently decolonised peoples would prove incapable of living democratically (as their ‘infantile’ anticolonial revolts supposedly demonstrated), and their states would reach the brink of collapse.13

In short, there was just one country capable of feeding its population and producing an agricultural surplus: the United States of America. The existential choice thus posed (and the Paddock brothers fancied themselves as advisors to the imperial prince) was the matter of who would be kept alive and who would be left to die. As against those tender-hearted dreamers who would use the US agricultural surplus as humanitarian aid,14 the Paddock brothers posed as realists: it was necessary to make a choice. To this end, they enlisted military medicine and its practice of triage. On the battlefield, it would be criminal to try to save those who were already lost, or to try and limit their suffering. The responsible doctor must, instead, concentrate his interventions on those whom he still stood some chance of keeping alive.

This martial metaphor was applied to the nations of the world, with Washington as the medical corps.15 The Paddocks then offered a review of which countries the US ought to help and which it should abandon. Was it much of a surprise that the first case they analysed was Haiti? This country is the historic symbol of emancipation, of the capacity of men and women of colour to free themselves from the slaveowner’s ‘wardship’ and to govern themselves.16 Th e Paddocks’ imperial outlook insisted that Haiti was a failure:

There is nothing whatever in sight that can lift up the nation, that can alter the course of anarchy already in force for a century … Now it is too late for an energetic, nationwide birth control program … Th e people are sunk in ignorance and indifference, and the government is entrapped in the tradition of violence. 17

Their judgement on India (a country whose government was ‘among the most childish and ineffi cient’), Egypt (a country with ‘no tradition within the people of being able to govern themselves and to solve their own problems – and the blame cannot be laid on the Turkish and British colonialisms’) and a number of other countries in the Global South was of the same paternalist and racist stamp.18 US help would have to go to its allies, especially those that did not give in to communist blackmail, and to countries that could be expected to control their populations. The global food crisis was put at the service of the US imperial project: ‘out of the experience of the Time of Famines’ would come ‘the foundation on which man built an era of greatness, an era of greatness not for the United States alone but also for the hungry nations’.19

Despite its wilder excesses, over the years following its publication the Paddock brothers’ book continued to be very widely used by neo-Malthusians. When it came to understanding the impacts that climatic fluctuations could have on agricultural production and thus on living conditions, their analyses would bear real influence.

COLD WAR AND CRISIS OF CAPITALISM

The convergence of environmental, security and population questions in the US in the post-war decades was thus an expression – and in part a critique – of that country’s imperial project.20 But if these responses looked at things through an American lens, what was really at stake was the survival of the capitalist system itself. Th is problem agitated a coterie of captains of industry preoccupied with the possibility of maintaining long-term economic growth, even under the constraints imposed by the exhaustion of natural resources. Th e Club of Rome charged Jay Forrester, a veteran of automated defence systems in the United States, with using his military know-how to model the global environment.21 Like most pioneers in simulating environmental systems, Forrester had been trained in cybernetics, decision sciences, game theory and systems theory. These sciences were supposed to make it possible to predict and understand the USSR’s behaviour in the global geopolitical game. Forrester, backed up by young professor Dennis Meadows’s team at MIT, used this system to predict the global evolution of resource consumption. Th ese MIT studies mark the point at which the Cold War met with environmental catastrophism. The models used for resource consumption were similar to those the RAND Corporation had used to model catastrophic military scenarios.22

The Limits to Growth, published in 1972, was the second study by this research group, following a work rhythm designed to influence the debates of the first UN conference on the environment, held in Stockholm that same year.23 This book had a planet-wide impact, and it continues to influence the terms of debate even today. Concern for the good long-term management of natural resources is necessary for capitalism. The vast post-1945 development of the state’s capacities for planning and intervention in resource management vividly illustrates what a mistake it is to take market apologists at their word and confuse capitalism with the free market. As Polanyi showed, state intervention was essential to establishing a laissez-faire economy; and a market society would be impossible without it. The state has always been the privileged, necessary site of the capitalist class’s action to extend its power and create the conditions for capitalist reproduction, as it seeks to extend both horizontally (more sectors of the economy, more territories, etc.) and vertically (within work, within domestic life, in leisure time, etc.).24 Since the end of the Second World War, the US state has not only played this role domestically, but, as an imperial state, it has sought to guarantee the conditions for the reproduction of capitalism around the world.25

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the US government, along with its close European allies, pressured for the treatment of environmental questions to become ‘global’. This strategy set them apart from the developing countries and the USSR, who instead preferred to defend countries’ sovereignty over their own resources. Under the direction of the Canadian industrialist Maurice Strong (who made his fortune in oil), the 1972 Stockholm conference and the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Climate: A Problem of Capital Importance

- Chapter One: Climate Crisis and Capitalism’s Survival

- Chapter Two: The Gospel of Flexibility

- Chapter Three: Climate and Market: The Double Shock

- Chapter Four: Climate Migrants: From Security Threat to Entrepreneurial Instrumentalisation

- Conclusion: Adapting Forever

- Notes

- Index