- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

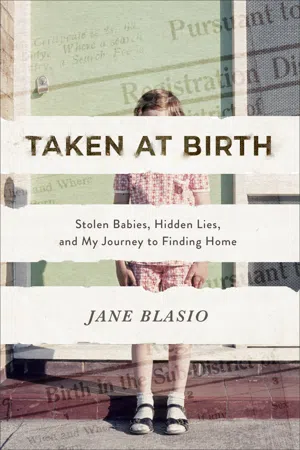

From the 1940s through the 1960s, young pregnant women entered the front door of a clinic in a small North Georgia town. Sometimes their babies exited out the back, sold to northern couples who were desperate to hold a newborn in their arms. But these weren't adoptions--they were transactions. And one unethical doctor was exploiting other people's tragedies.

Jane Blasio was one of those babies. At six, she learned she was adopted. At fourteen, she first saw her birth certificate, which led her to begin piecing together details of her past. Jane undertook a decades-long personal investigation to not only discover her own origins but identify and reunite other victims of the Hicks Clinic human trafficking scheme. Along the way she became an expert in illicit adoptions, serving as an investigator and telling her story on every major news network.

Taken at Birth is the remarkable account of her tireless quest for truth, justice, and resolution. Perfect for book clubs, as well as those interested in inspirational stories of adoption, human trafficking, and true crime.

Jane Blasio was one of those babies. At six, she learned she was adopted. At fourteen, she first saw her birth certificate, which led her to begin piecing together details of her past. Jane undertook a decades-long personal investigation to not only discover her own origins but identify and reunite other victims of the Hicks Clinic human trafficking scheme. Along the way she became an expert in illicit adoptions, serving as an investigator and telling her story on every major news network.

Taken at Birth is the remarkable account of her tireless quest for truth, justice, and resolution. Perfect for book clubs, as well as those interested in inspirational stories of adoption, human trafficking, and true crime.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Taken at Birth by Jane Blasio in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Sozialwissenschaftliche Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Stolen Babies

I THANK GOD for tattletales. If someone hadn’t gossiped like an old hen and let the truth out, no one would have ever known I was someone else’s child. My father was clear that he never intended on telling my sister, Michelle, and me that we were adopted, much less that we’d been bought from a clinic best known for abortions. When I first began asking questions, he lied, and when I was older, he admitted that he saw no reason to tell us the truth. My parents knew what they had gotten into when they bought two babies, and everything was, in their eyes, best buried deep somewhere. What a way to live, fearing every day that someone would show up at the house and take us from the front yard. Fear and shame are consequences of keeping secrets, especially when you have so much to lose when they can’t be contained.

My father was angry at the person who told his secret. My mother kept quiet because she was afraid. My parents wanted a baby desperately, and they had heard from my mother’s aunt Alice that they could get a baby for cash in North Georgia. Aunt Alice’s friend knew a doctor who was selling babies, and they made their way down there to get one.

Nestled in the Blue Ridge Mountains, the Hicks Clinic, which looks today like it did then, is a small, square, brick building the color of homemade butter pecan ice cream, the good kind. The simple, clean architectural lines of the building don’t hint at what took place inside. It sits just a stone’s throw away from the mild and soft-flowing Toccoa River that snakes its way quietly around McCaysville, Georgia, going deeper into Tennessee and becoming treacherous as it weaves through falls and rough rocks. Just a couple miles downstream, it transforms into the mighty Ocoee River, which is known for its whitewater rapids. The front of the Hicks Clinic faces one of the two main roads into the town, just across the street and down a-ways from the IGA store that straddles the Tennessee and Georgia line. If you were in the courtyard of the Hicks Clinic, you could watch the trains pass behind the IGA parking lot.

Doctor Thomas Jugarthy Hicks planted his building in the heart of McCaysville like you would plant a garden: methodically, one step at a time. The original Hicks Clinic was a house around which he placed offices and examination rooms. When the new clinic was built, the original structure was torn down. In old photos, nothing hints that the original building housed a medical facility or doctor’s office. The old structure stood in what’s now the courtyard of the Hicks Clinic.

Hicks tended the locals, mostly poor copper miners and their families, for colds, flu, and everyday medical mishaps, but he made his name and wealth through abortions and the sale of babies. He built his practice around the missteps of his life.

In the early 1940s Hicks was arrested and went to prison for selling drugs to the local miners and then lost his medical license and was barred from practicing in Tennessee. But after his release, the people of Georgia took him in and looked the other way long enough for him to open for business in McCaysville.

Hicks was a businessman first. That has never been questioned by anyone who knew him or knew of his practices—local families, workers from the copper mine, young girls seeking help, men needing a forged birth certificate to avoid or get into a war, and those who had to turn to him because they were unable to make it to a hospital. Patients could pay for his services by cash, check, or bartering, depending upon their economic status or inconvenient situation. Hicks’s reach included catering to the debutantes from Atlanta. He was the town doctor, abortionist, and baby seller. With prices ranging from one hundred dollars per baby in the 1940s to one thousand dollars per baby by the 1960s, Hicks sold newborns to barren couples from up North who were looking for babies to call their own.

My adoptive father didn’t want anyone to know about the Hicks Clinic or the long drives to McCaysville that he and my mother took to buy my sister and me. He especially didn’t want others to know about the doctor who was selling babies or the steady stream of women who ended up at the clinic to use the doctor’s services for many things my father most assuredly couldn’t speak of. The details of what went on at the clinic would be too much for many of our family members and friends. How do you explain buying a baby?

I was around fourteen years old when I saw my birth certificate for the first time. I studied it like an old-world map and used it to launch into many dreams of my birth story. I began piecing together my connection to the Hicks Clinic when I first laid eyes on the document, but my journey started years before on a crisp fall afternoon in Ohio. My first clear memory as a child was when I was told I had been adopted. It was late 1971. I was six years old. Radio stations played James Taylor and Janis Joplin, and President Nixon appeared on the television news. It was a perfect afternoon to play in the backyard.

Fall 1971

The warmth of the sun and the smell of leaves and dirt filled the afternoon air as I played with friends in our backyard. My sister came out to the back porch and called me to come inside. Michelle was ten years old to my six. Answering her as I dug my sneakers into the grass, I checked out my torn jeans. I’d be in trouble when Mom noticed. As I entered through the back door, expecting sweet smells of dinner and finding an empty table, confusion moved me across the room. It wasn’t until I passed through the kitchen that I saw the three of them in the living room, silent and scared.

Cigarette smoke filled the room, swirling upward to the ceiling and clinging to its surface. Sunlight filtered in from the kitchen and lit the corner of the living room where my parents were sitting on the sofa. The air was thick with tension, the tightness alarming. It put my guard up and burned the memory into me. Taking it in, I stopped abruptly, then slowly moved closer to stand before them. Jim and Joan Walters didn’t look like they were ready to share their news.

My father mumbled as he looked to the floor, speaking just under his breath. I could barely hear him. “We have something to tell you, and it may be hard for you to understand.” It was difficult to see him clearly, as he slumped just beyond the shaft of light coming from the kitchen. Cigarette smoke wrapped around his face as he brought his cupped hand to his mouth for another drag. Again silence.

The tension intensified and he finally raised his head without making eye contact, speaking toward Michelle, though not to her, even as she stood directly in front of him. “You heard from the kids on the playground that you were adopted?”

Immediately and through tears Michelle broke open, half screaming from the confusion of what she already knew and the fear of what she was about to be told. “Yes. They said I was a black-market baby too! They said you bought us!”

Even at my young age, I sensed that my father was embarrassed for the intrusion into his private dealings. He could say little more, dumbfounded that it would be so easy to unravel his well-laid plans. My mother’s family had always thought the transaction was suspicious, but they had never promised to share in keeping the secret. My father never wanted us to know.

My mother shook off the tension of the moment. Looking between both of us, she spoke with control and little emotion, opening the conversation. “You two were adopted. Do you know what that means?”

Innocent wonder made me look over to Michelle for a hint of what to do. She was my big sister and should’ve known how to react in that moment. I looked and looked until I realized she wasn’t looking my way. She had her head down, and she was crying. I was on my own. My mother turned her attention to me, irritation showing on her face. “How about you?”

I didn’t understand the tears or the drama, and I was okay with that, ready to escape. Half asking, half pleading, I jerked out a reply. “Can I go back outside?”

Relieved, she nodded, and I left them fast behind, busting open the screen door. The late afternoon air was a relief from the heaviness of the scene inside. The swing set beckoned me, and I sank into the faux leather of one of the seats, barely shaking the chains that attached it to its metal frame. I forgot about my friends playing out back as the sun was still bright but setting fast. All I can remember is how scared I felt. I’m not sure why; I just was.

My aunt Darlene came around the driveway side of the house, saw me in the yard, and came up to where I was sitting. She didn’t know what she was walking into when she stopped by the house. She was my dad’s sister, but she was ten years younger than him and was always looking out for Michelle and me. She would detangle my long hair ever so softly, make us peanut butter and jelly sandwiches with our favorite strawberry jam, and make sure we had a good time no matter what we were doing. She was close with and loyal to my parents and lived just down the street from us with Uncle Robby and Cousin Robin in the house Grandpa Walters built.

“What is a black market, Aunt Darlene?” I said, peering up at her through my crazy-cut bangs. She looked nervous, and that was odd, especially since she’d never looked anything but confident and mostly defiant. She took a breath, and I could tell she was thinking.

“Well, that’s a question, all right. Ask your dad.” She hesitated a moment, then added, “But not today, monkey. Wait awhile.”

I never asked him. It all seemed like too much to ask about. And who was I? My aunt didn’t bring it up with my parents until I was much older. I’m sure she was waved off and told to stay out of it. My parents had been caught red-handed and didn’t want any further talk. They didn’t realize their secrecy fueled my interest and a fire began burning, bringing to life in me a desire to know what it all meant for a six-year-old to be adopted and black market.

From that point forward the whispers became more evident to me; I heard more of the chatter. Almost wolflike senses appeared when I heard my parents whisper whenever anyone would say Michelle or I looked like them. Or more frequently, when my grandpa talked about how we were different or special. I began noticing how adult relatives smiled hard at Michelle and me every time we walked into the room, as if the uncomfortable grins would hide the elephant sitting in the corner holding a fake birth certificate.

Cousins would make remarks about us being made differently than they were. We were a special delivery of sorts. The neighbors had heard the stories and would share sad looks as my mother and father kept us in the backyard. My mother would all but have a breakdown if we strayed into the front yard or if a car rolled by too slowly out front, fearing someone would come to take us back. I remember the funny looks and comments from the kids at school who, themselves, didn’t completely understand why we were different in everyone’s eyes. Kids can be cruel and easily pick up on and react to the slightest tension or uncertainty.

Even if someone dared bring up the mystery surrounding my sister and me, how could you explain black-market babies to the third graders at Bettes Elementary School?

Spring 1974

The clock on the wall of the teachers’ lounge was ticking too loudly and too slowly. I wanted to go home, to hide. The third grade was not a place of refuge. Not for me. Not on this day or too many others that came after. The large, very blonde teacher on recess duty had brought me in and seated me in the teachers’ lounge to get me away from the other children. Three Dog Night blasted from the radio about Jeremiah the Bullfrog but I could still hear the teacher’s polyester pantsuit rustling as she hovered mountainous above me with a worried brow and pursed lips. She had found me huddled under a bush on the playground while the other kids laughed and kicked dirt my way.

A cousin of mine had overheard an adult conversation about my adoption. That day I absorbed some of the meaning of black market as she matter-of-factly told my classmates that I was paid for in cash like a dog at the store. “A puppy in the window. That’s what she is with her new outfit and pretty braided hair. Just a little dog with a new collar.” I was wide-eyed with the meanness of it all.

I vividly recall seeing my new red corduroy pants covered with dirt as I looked down at the ground and the children snickering, taunting, and pushing me to tears and confusion with words that I had never thought about or dreamt could be applied to me. As they continued their verbal assault, I stepped back and fell to the ground, kicking up a mess around me. There I sat under the dirt and leaves, now like the very dog I was accused of being, cowering from the blows. But I wasn’t a dog. I knew I was adopted but not that I had been bought.

I know now that I was too young to fathom the depth of it. Back then, nobody told me it was okay to ask or wonder about what was being said. They weren’t sure what to say to me since I was a child. And I wasn’t their child, so it was risky territory for an outsider or anyone wanting to stay in my parents’ circle of friends or relatives. The teacher had brought me inside to shield me from the children’s cruelty. She smiled a lot and did some low-level doting, wiping my hands and face off and attempting to clean my new outfit enough to look as normal as possible. I’m pretty sure she knew who I was and had heard the circumstances of my “adoption.” It was a close-knit neighborhood, and everyone knew who hung what on the line on laundry day. The story most assuredly got around way before I showed up on the playground that day.

I bolted out of the chair and ran when she told me I could go, never once looking up as my classmates moved out of the building as the bell rang for everyone to go home. I wanted to get away. Away from the big blonde hair and the sounds of barking that played over and over in my head. Embarrassment, confusion, and fear moved my legs and arms, propelling me away from the school and toward my house as fast as I could go. Running away from the children and their taunts that were stuck in my mind from earlier and were now a part of my lessons in trust and discernment.

These early lessons became the cornerstone of my fear of never finding the truth. They pushed me as I grew older. I began looking in every dark place, grasping at the tiny pieces of the puzzle I’d glimpsed that day on the playground. I collected everything and anything I could from an offhanded remark, a hushed conversation from my parents or grandparents, a torn page in the family Bible, or an odd number in my mother’s contact book. I kept my guard up like a lookout at a bank heist and romanticized the escape. I had to know. The search was on in my very young mind, and although I still wasn’t sure what I was looking for, I knew I had to find something, anything, to explain black market. On a cold, snowy break from school, my first attempt at direct-line questioning was merely the natural progression of my search.

Winter 1976

Snow covered everything, and at first, it brought the delight of afternoons playing outside, half-buried as we made snowballs and forts with the neighborhood kids and ran around pumped with adrenaline until we couldn’t feel our fingers or toes. We’d retreat into the warmth of home, only to thaw out and prepare to do it again once given the go-ahead. Snow. Thaw. Repeat. That’s a lot of work for a twelve-year-old.

School had been canceled for the third day in a row because of the onslaught of lake-effect snow coming in across Lake Erie with a vindictive streak, trickling down all the way from Cleveland to Akron. In the 1970s Akron public schools never canceled classes because of snow, so this was a rarity. But by day three I was bored and agitated from sitting around so long.

Having already exhausted almost every opportunity for entertainment outdoors, I decided it was time to explore the house. Curiosity overrode my sense of propriety and drove me upstairs to my parents’ bedroom to look for any forbidden thing lurking there. After rummaging through the closet and under the bed and finding little of interest, the dresser was next. Opening the top drawer and making a quick glance back to check that I was still alone, I gingerly touched each stack of my mother’s lingerie, fumbling over the softness to see if anything was hidden beneath. Nothing. I went to the next two drawers and repeated the same action, finding only souvenir stamps and silver dollars, leaving me to put all hope into the last drawer.

Finally, the dresser gave up its bounty. Under the thickness of sweaters and scarves, I found what at first glance looked like a scrapbook. I pulled it out and carried it to the table next to the bed. My mind reeled in anticipation as I slung my tiny frame across the mattress, grabbed the book, and settled in for the shameless invasion of privacy. I ran my fingers over the smoothness of the worn, pink quilted satin on the outside of the book and meticulously wound my way to the inside of the front cover. The cream-colored pages were decorated with hand-painted clouds in taupe and blue that floated among images of rattles and storks. The clouds were the backdrop to vital statistics that had been penned by a human hand.

Losing myself in numbers representing the weights and lengths of tw...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Endorsements

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1. Stolen Babies

- 2. Elvis Presley Sunday Religion

- 3. Promise Kept

- 4. Long Haul to Georgia

- 5. Casing McCaysville

- 6. And Other Stories

- 7. Walls Crumbled

- 8. Friend of the Family

- 9. 1997

- 10. Where the Babies Went

- 11. Just Past Nicholson’s

- 12. Sweet Tea and Fireflies on Blalock Mountain

- 13. The Rise and Fall

- 14. A Beautiful Dance

- 15. Taken at Birth—The Opening Act

- 16. Taken at Birth—Time Well Spent

- 17. Finding Home

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Back Ads

- Cover Flaps

- Back Cover