![]()

Part I

Visions

![]()

1

Flattened vision: nineteenth-century hot air balloons as early drones

Kathrin Maurer

‘Sometimes I felt like a God hurling thunderbolts from afar’, says a drone pilot of his experience operating drone missions.1 This God-like, all-encompassing view from the sky is often considered characteristic of military drone vision. Drones, executing a superior and powerful gaze from above, adhere to what has been called a ‘scopic regime’. The term was originally developed by scholars of visual studies to express the idea that not only what, but how we see is historically conditioned.2 In research on military drones, it is used to discuss the martial gaze of the drone machine and its human agents. Etymologically speaking, the Greek word skopos implies a direct connection between watching and waging war, as skopos can simultaneously mean both watcher and target.3 Drone vision thus instantiates a ‘militarised regime of hypervisibility’, granting the observer a powerful vertical, synoptic view of the target under surveillance.4

The idea that the drone enforces a scopic regime reflects (and in some ways reiterates) a well-established narrative of modern aerial vision: The eye in the sky is sovereign and all-seeing. The drone view, in particular, is often associated with being omniscient, precise, and surgical.5 But whereas military aerial vision can certainly be scopic, there is much more to be said. Military drone vision is much more complex and heterogenous than the scopic paradigm can describe. In this chapter, I focus on flattened vision as a central aspect of how drones and their agents perceive the world. In contrast to scopic vision, flattened vision is understood as a mode of perception that makes things even and levels them. Instead of a vertical and hierarchical perspective, flattened vision conveys two-dimensionality and the loss of depth. There is neither a central perspective nor a horizon. What remains in a flattened image are surface structures, abstract patterns, and clusters.

To demonstrate the longstanding importance of flattened vision to military sight, this chapter locates the drone’s antecedents in early analogue aerial technology. Instead of situating the drone in the context of contemporary digital surveillance technologies, it traces aerial sensing technology to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, exploring the vision field of hot air or gas balloons as technologies of visual flattening. The chapter argues that aerial vision cannot be exclusively understood as a scopic vertical mode of perception based on clear hierarchies, binaries, and oppositions. Rather, aerial vision is complex, incorporating many different perspectives, angles, and modes of seeing, with flattening crucial among them.6 Flattening indicates a specific mode of executing power through vision. No longer is it the vertical form of power exclusively. Rather, the flattened image executes a de-centralised network or grid of power. The flattened view, thus, still executes power and violence, and can be read as a form of dehumanisation, but does so no longer according to vertical hierarchies. Further, this historical comparison of balloons and drones de-fetishises the narrative about drone technology as the newest, game-changing technology. As the chapter demonstrate, drones, like balloons, have a history of unsteerability, unpredictability, and uncertainty; and comparing these technologies makes this evident.

I undertake the comparative approach as an experimental method that, resisting the narrative of scopic vision as the aerial perceptive of drones, helps to construct a new narrative of de-fetishisation. In this context, comparison proposes no causal relationship (balloon as cause for drone), nor does it construct a linear temporal connection between balloons and drones. It is better understood as an archaeological effort to find ‘family resemblances’, digging up the potential ancestors of today’s drone family.

The comparison will be effectuated primarily through an exploration of aesthetic works, that is, literary and artistic imaginings of ballooning and military drones. One certainly could have chosen to investigate historical documents, eyewitness accounts of ballooning, or photographs of the balloon view as more ‘empirical sources’. But I have chosen to use aesthetic, poetic, and fictional works as my primary source material, precisely for the faculty of aesthetic discourse to highlight the intricate relation between vision, technology, and power. The artificiality of these aesthetic aerial imaginaries should not be viewed as a drawback. Quite the opposite. Aesthetic imaginations highlight the complexity of aerial vision, richly and unpredictably reflecting on its violence and biopolitical effects.

Balloons and drones

At first glance, hot air or gas balloons and drones seem rather different. Balloons are beautiful colourful airships ascending serenely into the sky. Military drones, on the other hand, are noisy flying robots, or remote killing machines. Drones as combat weapons have been developed and utilised mostly in the twenty-first century, while balloons go back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In addition to drone’s digital imaging, the fact that they are remotely controlled could be viewed as another decisive difference between drones and balloons. Balloons are manned airships, and drones, by their very name – ‘unmanned aerial vehicles’ (UAVs) – fly alone. However, the first balloons were in fact unmanned, entirely without passengers. Later, to test the possibility of human survival at atmospheric heights, animals (sheep and chickens) were sent into the sky. It was only after animals had returned unharmed that humans took to the air. Many of these early manned balloons did not move completely freely, but were tethered to the ground by a rope.

The development from unmanned to ‘animal-ed’, and tethered to untethered, manned flight, makes one reflect on the notion of ‘unmanned-ness’ altogether. Considering ‘unmanned-ness’ in drones from the history of ballooning raises the question of how ‘tethering’ might be understood. Moreover, drones are never free to fly and float wherever they want to; they remain controlled by human agents on the ground. These agents are not physically present with the drone in the sky, but they are steering and flying it. Just as some balloons are tethered at the end of rope, the drone can be viewed as an extension of the drone operator’s joystick. Drone pilots are always connected to a command centre, in which military personnel examine the drone data and give orders to the pilots. Perhaps, in fact, there is nothing such as unmanned flight. Unmanned flight is our wishful fantasy, since we cannot be responsible for something that acts on its own and is totally free of human control.

But let us look at the beginnings of ballooning. On 5 June, 1783, only a few years before the French Revolution, the ancient human dream of flying came true in France when the Montgolfier brothers released their first hot air balloon into the sky. From that day on, engineers, enthusiasts, entrepreneurs, artists, and writers experimented with, improved, developed, and wrote about balloon flying technology. Félix Nadar was the balloonist popstar of the nineteenth century. His spectacular journeys and failures (such as the crash of his balloon Le Géant), as well as his early attempts to shoot aerial photographs from his balloons, still fascinate us today. Similar to what Caren Kaplan calls the drone-o-rama – the media hype around drone technology – balloons triggered a ‘balloonomania’.7 Aside from dramatic shows, hot air balloons also inspired fashion trends, influencing the design of clothing as well as fine china and porcelain figurines. Apart from featuring importantly in popular entertainment culture, balloons, like drones, with their dual usage in leisure and military contexts, were soon identified as potentially strategic tools in war.

As Joseph Montgolfier noted: ‘By making the balloon’s bag big enough, it will be possible to introduce an entire army, which, borne by the wind, will enter right over the heads of the English.’8 From their beginnings, balloons were instrumentalised in military battles for aerial reconnaissance, bombing, and transporting goods. For example, the balloon L’Entreprenant, owned by the French army in the battle of Fleurus (26 June 1794), was used to get a better view of the coalition army. Although the French won this battle, potentially also due to the balloon’s shock and awe effect, the French military’s use of balloons was interrupted when, in 1799, Napoleon disbanded the French Aerostatic Corps. French war balloons were in the air again during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the Siege of Paris. Balloons were also used in the Austrian-Venetian war and during the Civil War. Although these examples give proof of the balloon as a strategic weapon, their use never became widespread. They were simply too unpredictable and too unsteerable, and eventually superseded by zeppelins and aeroplanes. Nevertheless, intellectuals, military men, and engineers created powerful imaginaries of balloon weapon technology during the Napoleonic wars.

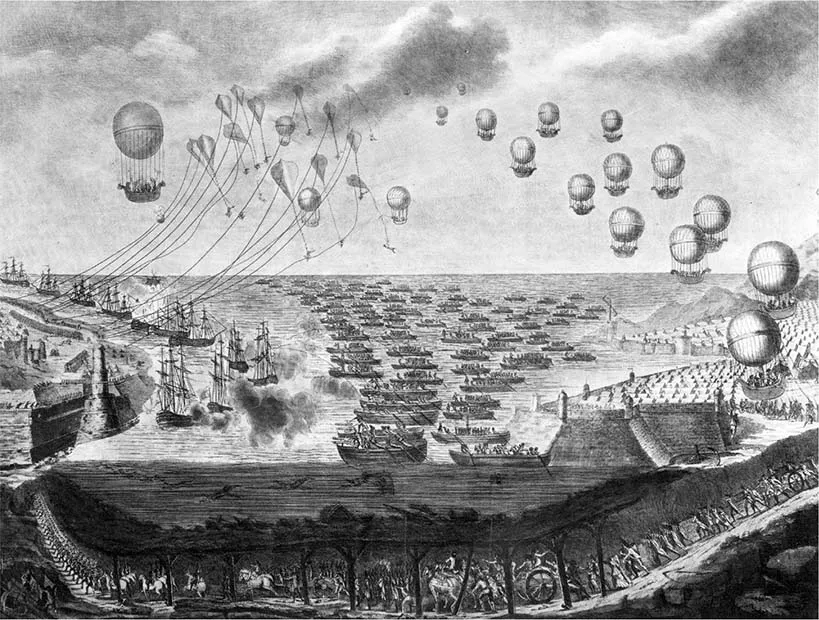

Take the image shown in Figure 1.1 about a fantastical invasion plan that would not only bring French troops to Britain via tunnel but also through an armada of aerial balloon warships. These aero-nationalist fantasies certainly express the political tensions of the Napoleonic Wars and embody the desire to conquer the enemy from the air. Balloons are here imagined as a super-weapon that, by delivering a sovereign view of the battlefield, promises victory. Although, in the end, this did not happen for Napoleon, my point is that the balloon’s sovereign gaze is, equally, a powerful fantasy. However, aesthetic imaginaries in art and literature of the balloon gaze can demonstrate a very different kind of aerial vision and power relation, which is discussed in the following section.

1.1 Invasion of England, 1804, French engraving. Imaginary view of Napoleon’s invasion of England using ships, balloons and a tunnel under the English Channel.

Flattened vision of balloons

Many late eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary authors were inspired by balloons. An early German author whose reflections on ballooning were particularly influential was Christoph Martin Wieland. In the journal Der Teutsche Merkur, Wieland praised the new flying technology as a product of rational progress, but adopted a sceptical attitude towards its popularisation. He coined the satirical term ‘Aeropetomanie’ to describe the public’s obsession with balloons during his time. Heinrich von Kleist, Arthur Schopenhauer, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe also wrote diary entries, letters, and essays about ballooning.

Most interesting for a discussion of flattened vision is the work of romantic author Jean Paul in his text The Diary of the Aeronaut Giannozzo (1801) [Des Luftschiffers Giannozzo Seebuch (1801)], about a balloon journey.9 This work is the appendix to his novel Titan (1800–1803), a 900-page work about the life of the Spanish aristocrat Albano de Cesara. Whereas Titan contains some classical elements of the traditional ‘Bildungsroman’, The Diary of the Aeronaut adheres more to Jean Paul’s romantic, highly self-reflexive style of writing. The Diary of the Aeronaut represents a form of travelogue, with references to actual places (such as small German Dukedoms and cities), historical figures (Frederick II), and historical events. The protagonist Giannozzo is the travelogue’s fictive author, while Jean Paul inserts himself as the editorial figure Jean Paul Fr. Richter, commenting on Giannozzo’s story from time to time, as well as adding footnotes to the main text. As the protagonist Giannozzo hovers in his balloon over the small dukedoms of Germany, he issues a scathing critique of bourgeois society’s narrow-minded view of life, its religious rituals, and its lack of intellectualism. While literary research has often focused on Jean Paul’s critique of German bourgeois pre-revolutionary society, I am mostly interested in how The Diary of the Aeronaut represents the balloon as a technology of seeing.10

In Jean Paul’s text, the...