![]()

PART ONE

PERSPECTIVES

![]()

1 AN ILLUSTRATED FIELD GUIDE TO FUNGAL AI FOR DESIGNERS

David Kirk, Effie Le Moignan and David Verweij

When we are designing digital technologies, we are often inspired by patterns we see elsewhere and seek to replicate them, as metaphors and analogies, in an effort to make the interfaces to those technologies easier to use or more understandable for the user (Norman, 2013). This is as true for interaction design as it is for product design, two fields which are increasingly interwoven (Rowland, Goodman, Charlier, Light & Liu, 2015). We are moving towards a world of smart domestic products and devices, networked artefacts that connect both to us and to one another, imbued with the vestiges of ‘intelligence’. Consequently, it is likely that we will continue to need to utilize metaphor and analogy to make these devices intelligible to their users (ibid.).

Within interaction design, the discussion of the role of metaphor and analogy at the interface has formed an extensive part of an ongoing debate about the nature of what some term ‘Natural User Interfaces’ or Reality-Based Interaction (Jacob et al., 2008). However, as we think through how future intelligent devices will interact with us, we might question exactly how notions of intelligence are constructed. Where do we find the examples of intelligence that we draw upon, for our inspiration and our metaphors, and what are the assumptions and implications hidden within these metaphors?

Webster and Weber (2007) highlight the characteristics of fungi which differentiate them from animal and plant life. As stationary forms sited on a substrate host material, fungi feed by absorption of nutrients from the environment. The enzymes produced by fungi render nutrients available by breaking down the cells of the host material, for absorption. This leads to a wide range of fungal forms suitable for diverse environmental conditions, from single-celled yeasts to complex mushrooms. These range in ecology from those which are freeform, to those mutually symbiotic with a host, to the parasitic and hyperparasitic (ibid.). As a result, fungi are a ubiquitous presence in terrestrial and freshwater environments (Dix and Webster, 1995), with a massive number observed and predicted to exist, ranging from a conservative 1.5 million species to 9.9 million species globally (Hawksworth, 2001). Fungi form the largest biomass in soil, act as decomposition agents for dead materials and pathogens, make nutrients bioavailable to plants and have roles in the nitrogen and carbon cycles (Gadd, Watkinson & Dyer, 2007). Fungi produce spores which facilitate their spread, but additionally can form substantial mycelium networks which penetrate the soil, forming extensive networks (Webster & Weber, 2007). These networks are symbiotic with plants, acting as chemical communication networks signalling to a plant when another nearby is under attack from aphids (Babikova et al., 2013). Fungi are complicated, multiform and act in ways which serve to interact and respond to their environment that are deeply and fundamentally different from those in which humans or animals do.

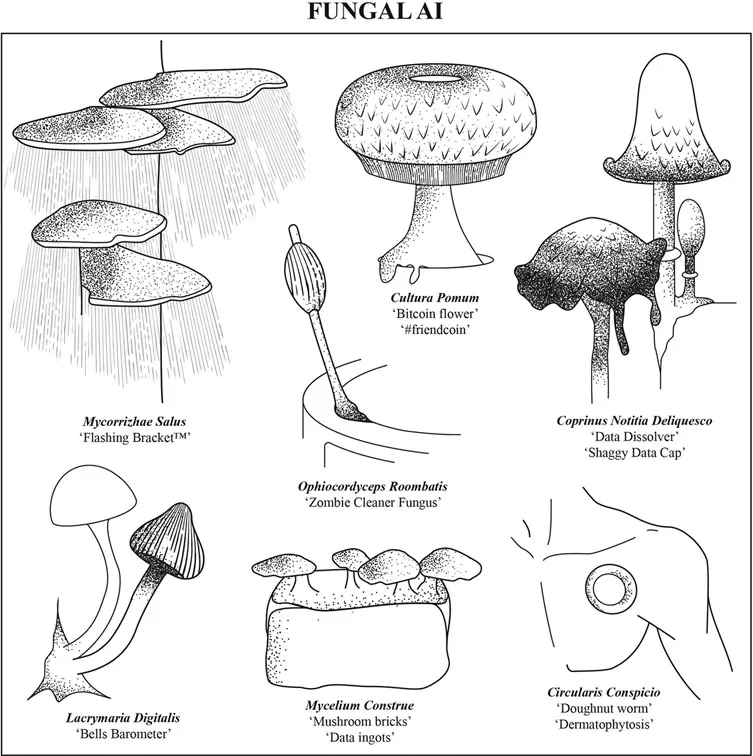

Using the diverse and unusual characteristics found within fungi, we utilize them within this chapter as a metaphor for exploring AI in everyday settings, focusing on the home (as a typical site for encountering ‘smart objects’). Presented as a brief illustrated guide to seven conceptual forms, we introduce the notion of ‘Fungal AI’ as a provocation for design, exploring the idea of drawing on mycology (the study of mushrooms and fungus) as a novel source of inspiration for the design of smart objects. Fungi have long been utilized for a range of practical purposes, from baking and brewing with yeasts, as foodstuffs, for medicinal properties and for religious and cultural use as hallucinogens (Boa, 2004; Milenge Kamalebo, Malale, Ndabaga, Degreef & De Kesel, 2018).

In this chapter we begin to explore the characteristics of fungi as a starting point of speculation for future design, in contrast to more commonly employed anthropomorphic and zoomorphic approaches to the design of interfaces, and look at the play of possibilities (Anderson, 1994) when using alternative conceptions of intelligence.

Useful properties of fungi or mushrooms

Fungi, quite broadly, offer some potential properties, which we might utilize as primary design characteristics for inspiration and which may mark them out as distinct from other kinds of intelligence that we routinely encounter.

With a concept such as a fungal AI, there might be two possible interpretations – the first is that we are advocating some kind of complex bioengineering in which fungal DNA is very literally made synthetic and algorithmic in a way where we can very literally create new forms of life. The second idea we are advocating is that, as a design community, we might take inspiration from fungal properties, through metaphor, to explore new kinds of AI-like systems, new smart services and technologies, for domestic life (for example) that draw on the kinds of properties that can be found in the fungal world. It is this latter interpretation of the concept of fungal AI that we are hoping to pursue herein.

Whilst fundamentally complicated in terms of the biological structures and chemical processes which occur in some fungi, there are key points which render them as suitable for consideration in terms of AI systems. Broadly, one of these is that fungi require a substrate base on which to proliferate and to provide access to resources needed to thrive. This makes them ideally suited to system design concepts of embedding, input and output, and, for example, working with the everyday residua of smart objects such as data traces and network traffic. Fungi respond to their environment, monitoring and adapting to conditions, thereby showing learnt behaviours akin to the machine learning of ‘smart objects’. It is worth noting that these characteristics, which might underpin the metaphor, are readily understood by the non-expert. It is of note generally that fungi

● are orthogonal to human desires and intentions and exist in their own right (have their own needs, goals, and so forth)

● make no attempt to interact directly with us but provide functional value to humans, animals and plants

● grow, learn and adapt to different ecologies

● propagate themselves (sometimes with support of other organisms)

● this action can be facilitated by providing appropriate ‘sites of propagation’

● coexist with humans in our spaces (and on/in our bodies)

As fungi do not communicate or appear as directly responsive, they represent a departure from other forms of life. It is relatively easy to ascribe intelligence, motive or characteristics onto animals, for example. This is due to similarity in form, such as having a face, and overlapping needs for food, warmth and shelter. We can recognize playfulness, sociability and states of being. However, it is more challenging to speculate around intelligence which is divorced from embodied forms and states we can identify with – or indeed easily project an illusion of familiarity upon (whether this is accurate or not). Fungi are intensely responsive to their environment (albeit at temporal scales which feel alien to us or are hard for us to perceive), using it as the very material on which to grow and derive their nutrients from. Whilst some forms exist in symbiotic or parasitic forms, they are generally self-contained and independent. There is no ‘window into the soul’ to interpret or interact with a fungal form. One can provoke a response by changing the environment, which is observable. It can be viewed as naturally spreading and encouraged to grow by propagation. However, the needs of fungi are functional, and their existence is very alien to us, despite the fact that we often share our homes (and even our bodies) with these ‘intelligent’ life forms.

Ultimately, the benefit of fungal AI systems to people might be quite tangential – we might design/cultivate a fungal AI and find that it is performing some kind of function or offering some kind of service that we can farm – that we can take advantage of whilst it is in essence ‘doing its own thing’.

Spotting common fungal AI in the wild

In this section we provide an alternative design fiction in the form of a set of preliminary written field notes on different kinds of AI mushroom morphology and how one might encounter them in the wild – each of which shows a fungus-like AI working in a different way – each offering different tangential functionality to humans. We situate these fungal AIs (illustrated in Figure 1.1) primarily in the domestic space, to note the common way in which we live alongside these often unremarkable but useful life forms and because they speak to the prevalent locations in which we might encounter smart objects. This allows us to begin to demonstrate the utility of the metaphor and to explore some of the play of possibilities engendered by the concept of fungal AI.

Lacrymaria digitalis

Bells barometer

[Distribution] Large areas of Europe and North America and most temperate zones with inclement weather, particularly common in the north-east of England

[Habitat] Grows/propagates near damp and cool surfaces such as windows where there is a clear line of sight to external precipitation and audible sound of rainfall

[Properties/behaviours] Estimates rainfall for central data collation by measuring onset and offset of rain sounds. Will learn to bloom with the imminent onset of precipitation. Can be used to provide rainfall data for passing apps.

[Visual description] Pinkish in colour, with light brown gills, fruiting body can tend towards the tear shape

Coprinus notitia deliquesco

Data dissolver; Shaggy data cap

[Distribution] Whole of Europe or any General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR)-compliant zone

[Habitat] Likely to be found growing on or around wireless-connected security systems in domestic environments

[Properties/behaviours] Grows in size as it aggregates domestic movement and activity data from nearby building/security sensors. Learns and archives patterns of movement for specific occupants. Using digital mycorrhizal connections, fruiting body data will be exchanged with smart thermostats to dynamically correlate heating/cooling requirements with occupancy and activity measures. When building occupants have left for an extended period of days, the mushroom will dissolve itself in an autodigestion process, purging personally identifiable data and leaving behind a pool of data residua, which serves as an algorithmic growth medium for new blooms or can be archived as an historic resource of privacy-preserved building data.

[Visual description] Tall white caps, somewhat scaly. The gills beneath are white when young but then turn inky black and dissolve when data is decomposing.

Ophiocordyceps roombatis

Zombie cleaner fungus

[Distribution] Wide geographic spread – both northern and southern hemispheres, mostly in industrialized areas, particularly common in ‘smart homes’

[Habitat] An iotopathogenic fungus currently found predominantly in smart homes, specifically infecting models of the iRobot Roomba Robotic Vacuum species

[Properties/behaviours] Full pathogenesis will be enacted by the host device (Roomba) having its behaviour artificially manipulated. The fungal AI influences and reprograms intelligent circuitry; in particular, infected Roombas will have their navigation altered. By manipulating t...