![]()

Trouble in Armagh, 1784–1798

The first disturbances we had in the north of Ireland, that I recollect, were in the county of Armagh.

James Christie

On 7 July 1796, Edward Cooke, the under secretary in Dublin Castle, wrote a concerned letter to Lord Gosford, the Lord Lieutenant of County Armagh. In this letter Cooke vividly described the recent ouster of Catholic tenants from their homes in north Armagh and the Armagh-Down borderlands. “My Lord Lieutenant learns with the utmost regret that outrages still continue in the county of Armagh and that those persons who style themselves Orange Boys are persecuting the lower orders of the Catholics with great cruelty—burning . . . their houses and threatening the lives of those who will employ them.”1 Like many other contemporary observers, the under secretary proceeded to blame the crisis in Armagh on the inactivity of its weak gentry class.2 To remedy this situation Cooke argued that the county gentry needed to reassert social control over their lower-class coreligionists. Unfortunately, Cooke’s prescription for resolving the crisis fell far short of his rather insightful analysis. In the end, his only suggestion was that the county magistracy should meet in a show of solidarity against the violence.

The disturbances that Cooke described occurred throughout late 1795 and 1796, when vengeful Protestant gangs called Peep O’Day or Orange Boys drove Catholic tenants and their families from the weaving districts of mid-Ulster. Estimates range widely, but somewhere between four thousand and five thousand Catholics fled mid-Ulster in this two-year period. Many of these families traveled to the remote climes of North Connacht, finding new homes in the counties of Mayo and Galway.3 Ironically, these northern exiles played a critical role in spreading both the revolutionary ideology and organizational structure of the Defenders and the Society of United Irishmen to the west of Ireland. Not surprisingly, bloodcurdling (and increasingly exaggerated) tales of Orange persecution and massacre in Armagh proved to be an excellent recruiting sergeant for the United Irishmen throughout Ireland.4

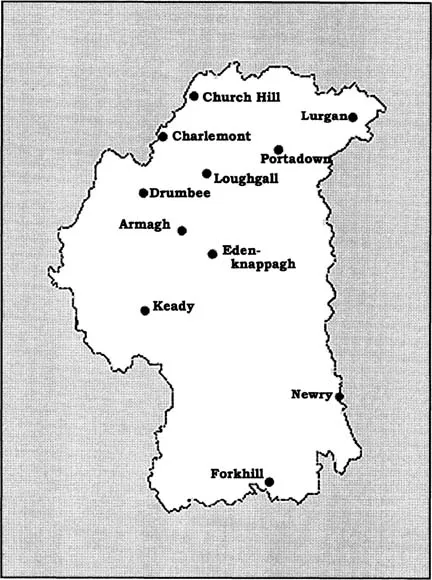

County Armagh.

The Armagh expulsions of 1795 and 1796 constituted the last phase of a protracted communal conflict between the Peep O’Day Boys and the Defenders that raged on and off in County Armagh and its surroundings between 1784 and 1796. Known to historians as the Armagh troubles, these sectarian disturbances played a significant role in pushing Ireland toward revolution in the 1790s. Two of the primary organizations of revolution and counterrevolution in late eighteenth-century Ireland, the Defenders and the Loyal Orange Order, emerged directly from County Armagh. Not surprisingly, a number of historians have examined these disturbances in some detail, offering quite disparate interpretations of the forces behind these critical events.5

The scholarly debate on these disturbances largely has centered on the question of motivation; on what precise role economic and political forces have played in triggering the violence in Armagh. Although these analyses often have been quite creative and insightful, no scholar has yet offered a satisfactory interpretation of the Armagh troubles.

In searching for a more inclusive and comprehensive account of these critical events, E.P. Thompson’s concept of the moral economy serves as a useful tool for fusing the various political, economic, and cultural forces that shaped this long-running sectarian conflict. The idea of the moral economy first emerged in Thompson’s classic 1971 article on food riots in eighteenth-century Britain.6 Rejecting the traditional view that such clashes were spasmodic reactions to economic grievances, Thompson asserted that the participants’ actions were grounded upon “a popular consensus as to what were legitimate and what were illegitimate practices in marketing, milling, baking, etc. This in turn was grounded upon a consistent traditional view of social norms and obligations, of the proper economic functions of several parties within the community, which, taken together, can be said to constitute the moral economy of the poor.”7 According to Thompson, this consensus derived much of its legitimacy from the rioters’ selective reconstruction of the traditional paternalist model of food market regulation. In fact, he found that the moral economy of the eighteenth-century English poor largely reproduced the provisions of the Book of Orders, a series of emergency measures enacted in times of crisis by the English government between 1580 and 1630. Many food rioters thus believed that they were playing a magisterial role, enforcing their conception of traditional British law against violators of customary practice. While certainly controversial,8 Thompson’s work helped to revolutionize the way we look at collective action, inspiring a generation of scholars to explore the cultural milieu from which popular violence emerged.

Two aspects of the moral economy argument make it a particularly useful framework for the study of Ulster’s tradition of sectarian violence. First, by emphasizing the importance of traditional communal expectations in explaining outbreaks of popular violence, it focuses on the issue which lies at the heart of partisan contention in the north of Ireland: the continued relevance and vitality of two interlocked but conflicting visions of how Irish society should be structured. In an important book on Belfast’s troubled history, Jonathan Bardon states that “historians have been a little too ready to blame the symptoms rather than search for the underlying causes of this sectarianism, which has its roots deep in Irish history.”9 Thus, most of the works devoted to sectarian contention in late eighteenth and nineteenth-century Ulster focus their attention on organizations and institutions like the Peep O’Day Boys, the Defenders, and the Orange Order.10 Because it focuses on the beliefs and expectations that gave rise to sectarian clashes, the moral economy framework allows the scholar to move beyond the institutional level, a step that is critical if we are to better understand the evolution of modern political culture in the north of Ireland.

By showing how food rioters used selective reconstructions of the past to legitimize their actions, Thompson’s article also stressed the important role played by popular conceptions of history in the prosecution of collective violence. This idea nicely echoes the tradition of conflict in Ulster, where both Catholics and Protestants used mythic narratives of the Irish past to justify their actions. Indeed, popular depictions of history often lay at the center of sectarian riots. At partisan festivals throughout the year, both parties constructed two conflicting accounts of Irish history in elaborate displays of public ritual, provocative rites that gave rise to some of the largest sectarian riots of modern Ulster history.

The Armagh troubles began in the early 1780s because mid-Ulster loyalists perceived that powerful forces were working to overwhelm the sectarian moral economy. The notion of a sectarian moral economy refers to Protestant plebeian expectations regarding their relative position in Irish society. This worldview consisted of a series of presumptions regarding relationships with two broadly defined social groups: Irish Catholics and the Protestant elite (and implicitly, the British state).11 When both of these relationships were called into serious question in the late 1770s and 1780s, hardline loyalists in mid-Ulster mobilized into action, attempting to enforce their understanding of their traditional rights on the ground.

The sectarian moral economy centered on an exclusivist definition of loyalty and citizenship.12 Put simply, a sizable majority of Ulster Protestants believed that they had a historic right to superior status over their Catholic antagonists. This belief system had rather straightforward political and economic ramifications. The economic provisions of the sectarian moral economy consisted of a vague sense that Protestants had earned the right to a position of relative economic advantage over Irish Catholics. The Protestant tenant-farmer/weaver in County Armagh did not have to be prosperous (which was lucky for him, as most were not!), but the sight of a Catholic neighbor accumulating wealth was a clear violation of this communal code. More importantly, the loyalists believed that Catholics should be kept down politically—excluded from the Irish polity. Of course, in the late eighteenth century, politics had nothing to do with the franchise for the vast majority of Irish Protestants. For the rank-and-file loyalist, privileges like the right to bear arms and expectations of partisan judicial favoritism were what separated the plebeian citizen from those outside the political pale. As we will see, the right to bear arms was particularly critical. This was not merely about maintaining communal ascendancy over one’s foes (although holding a monopoly on weaponry certainly went far in that direction). The right to bear arms also conferred a certain measure of citizenship and above all, a special status to plebeian Protestants.

Like Thompson’s food rioters, the ultra-Protestants’ exclusivist conception of citizenship was grounded in a selective reconstruction of history. This belief system derived much of its legitimacy from a widespread mythic view of the Irish past that emphasized both the barbarism and revanchism of Irish Catholics—an ideology typically encapsulated in reductionist fashion as a siege mentality.13 This historical narrative generally focused on the bloody events of the seventeenth century, when Irish Catholics twice rose in rebellion against both Protestant settlers and the British Crown. For loyalists, these events offered ironclad proof that Irish Catholics were not to be trusted with full citizenship rights. Ulster Protestants, by way of contrast, had continually earned their ascendant status throughout these years, maintaining a record of steadfast loyalty and exemplary military service.

But hard-line loyalists did not justify the sectarian moral economy solely in terms of their own perceptions of communal fidelity. Their exclusivist notion of citizenship was also grounded in a popular interpretation of the British constitutional settlement of the late seventeenth century. Plebeian Protestant conceptions of their historic rights were not solely based on illusory myths constructed by members of the Protestant lower classes desirous of maintaining their ascendant status over their Catholic adversaries. They reflected a not entirely inaccurate perception of British law in Ireland. After all, the exclusivist provisions of the Penal Laws provided much of the basis for British governance in eighteenth-century Ireland. In many ways, loyalist expectations regarding communal relationships accurately reproduced the formal terms of penal legislation enacted against Irish Catholics in the early eighteenth century. And these laws were hardly a distant memory. As late as 1780, laws excluding Catholics from formal politics, banning their right to bear arms, and restricting their economic wherewithal existed on the statute books.14 When the Peep O’Day Boys traversed the weaving districts of north Armagh in search of Catholic arms, they were merely enforcing laws that the naive gentry had allowed to languish. These men clearly saw themselves as defenders of the true Protestant constitution—plebeian magistrates of true British law.

But the sectarian moral economy was not only concerned with regulating communal relationships. It also mapped out a general set of rules and obligations for true Protestants. These generally flowed from assumptions regarding habitual Catholic disloyalty.15 Working from this premise, loyalist ideology emphasized the need for cross-class Protestant unity (which Frank Wright has termed pan-Protestantism) against the revanchist Catholic threat. Particularly important was the special relationship between lower-class loyalists and the Protestant elite. From a plebeian perspective, the standard for this critical relationship had been established with the penal laws, when both the British government and the Irish ruling classes had rewarded Protestant loyalists by giving them a perpetual right (or so they believed) to an ascendant status over Catholic rebels. By the late eighteenth century, plebeian Protestant activism thus represented a call for the return of traditional partisan paternalism.16 The notion that plebeian Protestants’ historic service had earned them the right to a special relationship with the Protestant gentry lay at the heart of the sectarian moral economy.

Not surprisingly, the worldview that dominated Irish Catholic popular culture differed fundamentally from its loyalist counterpart. This belief system focused on the historic deprivation of the Irish Catholic church and its adherents. At the heart of this mythic narrative lay an understandably deep well of bitter resentment centered on the formal exclusion of Catholics from many critical aspects of Irish society. This sense of dispossession was represented most tangibly in the eighteenth century by the relatively recent loss of landholding rights. The resolute attachment of Irish Catholics to the land of south Ulster would play a central role in the expansion of sectarian antagonism in the late eighteenth century.17

Like its Protestant counterpart, this Catholic worldview derived much of its legitimacy from a particular view of the Irish past, a narrative that focused on the status and power lost to Protestant conquest over the previous two centuries. But for all the basic parallels, it would be wrong to view this belief system within the conceptual framework of the sectarian moral economy. The moral economy is essentially a conservative notion, an ideology concerned with preserving the vitality of traditional practices against the onslaught of innovation. For very understandable reasons, Ulster Catholics were not particularly interested in preserving what they had. Instead, their conceptual grid was essentially restorative, a worldview that centered on the need to regain what had been taken from their ancestors. Above all, northern Catholics aimed to resist and roll back the imposition of the sectarian moral economy.

The notion that Ulster Protestants and Catholics had diametrically opposed worldviews is not particularly novel. But it is critical to reiterate these fundamental communal beliefs, for they lay at the heart of Armagh’s sectarian warfare in the 1780s and 1790s. The final decades of the eighteenth century were the most traumatic and turbulent years in modern Irish history. To many observers both political and economic trends seemed to open up the possibility of a dramatically new type of Irish society—a vision of the future that challenged both Protestant and Catholic conceptions of how Irish society should be run. The threat to traditional plebeian Protestant expectations regarding their status within Irish society proved to be particularly important, for it was largely the widespread fear of betrayal among lower-class loyalists that drove the Armagh troubles forward.

On the political front, the late 1770s and early 1780s saw a number of attempts to curb some of the worst abuses of the eighteenth-century Irish polity. Pushed forward by a loose coalition of the Irish Protestant elite, generally labeled Patriots, these reform attempts satisfied very few Irish men and women. They both threatened the lower-class Protestant interpretation of the constitutional settlement and whetted the Catholic appetite for more substantial reform measures.18 By challenging the status quo, these political reforms mobilized two substantial social groups with irreconcilable goals. But it was not merely political developments that drove this crisis forward; structural changes in the Ulster economy also played a critical role in creating an environment ripe for outbreaks of sectarian violence.

The growth of the northern linen economy (centered on mid-Ulster’s famous linen triangle) threatened the communal status quo in a myriad of ways.19 By opening up potential avenues of socioeconomic advancement for Catholic weavers and merchants, the expansion of the linen trade seemingly increased economic competition for Protestants involv...