Community Visioning for Place Making

A Guide to Visual Preference Surveys for Successful Urban Evolution

- 358 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Community Visioning for Place Making

A Guide to Visual Preference Surveys for Successful Urban Evolution

About this book

Community Visioning for Place Making is a groundbreaking guide to engaging with communities in order to design better public spaces. It provides a toolkit to encourage and assist organizations, municipalities, and neighborhoods in organizing visually based community participation workshops, used to evaluate their existing community and translate images into plans that embody their ideal characteristics of places and spaces. The book is based on results generated from hundreds of public participation visioning sessions in a broad range of cities and regions, portraying images of what people liked and disliked. These community visioning sessions have been instrumental in generating policies, physical plans, recommendations, and codes for adoption and implementation in a range of urban, suburban, and rural spaces, and the book serves as a bottom-up tool for designers and public officials to make decisions that make their communities more appealing. The book will appeal to community and neighborhood organizations, professional planners, social and psychological professionals, policy analysts, architects, urban designers, engineers, and municipal officials seeking an alternative vision for their future.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

1

Using Visual Preferences and Vision Translation Workshops for Place Making

Now think of the power we call vision; that inner sight which encompasses the larger meaning of its outer world, which sees humanity in the broad, which beholds the powers, which unifies its inner and outer world, which sees far beyond where the eye leaves off seeing, and as sympathetic insight finds its goal in the real.

The vast majority of people have similar positive or negative responses to the same places and spaces. A key to a positive physical future is determining those places and spaces that resonate positively in most peoples’ minds and then translating these into plans and codes that are built.

How appropriate or inappropriate are these spaces and places now and in the future for this community?

Depressed | 46% |

Hopeless | 10% |

Threatened | 7% |

Anxious | 4% |

Fear | 4% |

Rage | 3% |

All the above | 26% |

Hopeful | 25% |

Joy | 16% |

Happiness | 19% |

Safe | 9% |

Pride | 6% |

All of the above | 25% |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One Introduction to Community Visioning

- Chapter Two The Progression of Urban Change

- Chapter Three Research, Development, and Results

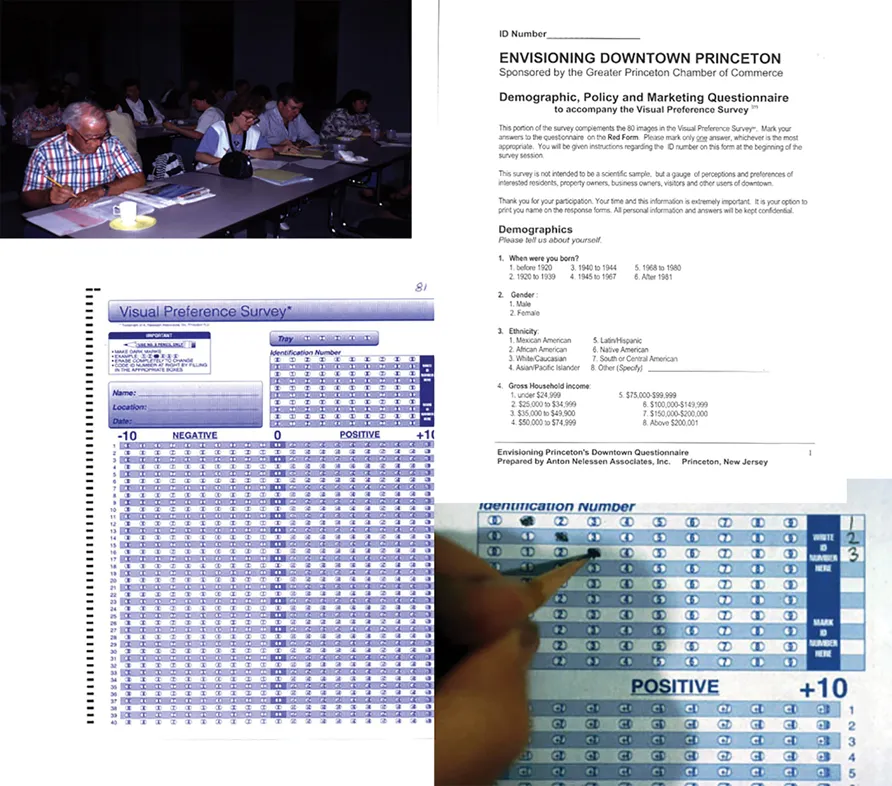

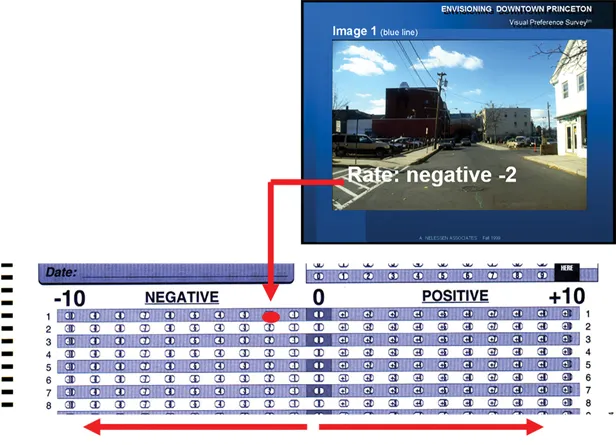

- Chapter Four Measuring Visual Responses for Place Making

- Chapter Five Ten Steps for a Successful Community Visioning Process

- Chapter Six A Community Visioning Session

- Chapter Seven Prologue to the Five Vision Focus Areas

- Chapter Eight Vision for Natural Landscapes

- Chapter Nine Visions for Rural Lands

- Chapter Ten Visions for Suburbia

- Chapter Eleven Visions for Small Towns

- Chapter Twelve Visions for Urban Cores of Large Cities

- Chapter Thirteen Communicating Vision Preferences—Recommendations and Realizations

- Chapter Fourteen The Future of Planning and Public Engagement

- Chapter Fifteen Why I Am Hopeful and Sometimes Not

- Appendix I Definitions

- Appendix II Communities from Which the Visions Were Generated

- Appendix III Typical Responses from the “Book of Public Comments”

- Appendix IV Bibliography

- Index