![]()

1 Lubitsch’s Career

Lubitsch himself had multiple beginnings. As the favourite son of a Russian émigré who ran a clothing shop ‘for large women’ in Berlin, Lubitsch first began as a rather incompetent clerk in the family firm. Then he began an acting career as a nineteen-year-old protégé of the great Max Reinhardt, the revolutionary stage director. Lubitsch’s short stature and facial features – a cross between a cherub and a gargoyle – meant he could never play the lead, but he brought character and energy to the smallest role. These qualities come through in his screen acting debut as a marriage broker catering to the needs of finicky men in Die ideale Gattin (The Ideal Wife) (1913). Only twenty-one, Lubitsch looks older (and unrecognizable), thanks to a fake beard and moustache. His screen credit as ‘Karl’ Lubitsch perhaps reflects a stage actor’s doubts about the artistic legitimacy of film performance. If so, those doubts dissipated once Lubitsch started directing himself, as in Als ich tot war (When I Was Dead) (1916). (He had directed at least seven films before this one, but these are either lost or fragmentary.) In this film about a man who solves his marriage problems by pretending to be dead, only to take a job as a servant (thinly disguised by a wig) in his own home so he can be around his wife, Lubitsch not only takes screen credit under his real name but also plays a character called ‘Herr Ernst Lubitsch’.

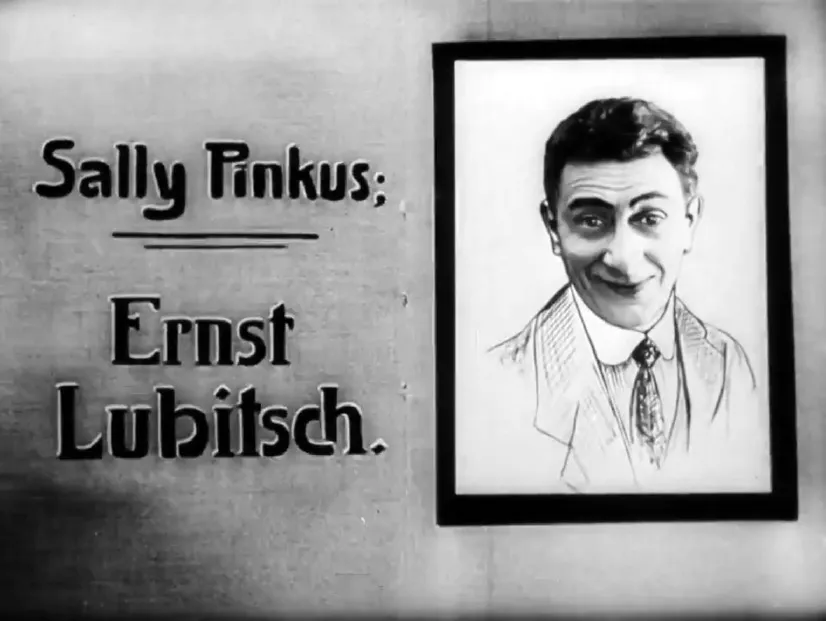

The shop clerk turned actor turned director combined all three vocations when he directed himself in Schuhpalast Pinkus (Pinkus’s Shoe Palace) (1916), a highly successful Lustspiel (comedy). Lubitsch plays the role of Sally Pinkus (Sally, pronounced ‘Solly’, is short for ‘Solomon’), a young man who fails his way to success by getting expelled from school and fired as an apprentice shoe salesman. He is on the verge of being fired from a second shoe job when he alters the label on a pair of slippers to stroke the vanity of a wealthy woman so she will think her feet are smaller than they are. She is so charmed by Sally that she finances his own ‘Shoe Palace’. After he hustles his way from schlepp salesman to stylish entrepreneur, Sally is on the point of writing the woman a cheque to repay the loan but suddenly has a better idea: ‘But why divide it up? Marry me and it’ll all be in the family.’ The woman accepts the two-for-one deal – she gets Sally as both husband and business partner. Pinkus’s Shoe Palace was the most successful of the several ‘store comedies’ featuring Lubitsch, including the one that made him a star, Der Stolz der Firma: Die Geschichte eines Lehrlings (The Pride of the Firm: The Story of an Apprentice) (1914), directed by Carl Wilhelm. Indeed, critics regard Pinkus’s Shoe Palace as a near-remake of The Pride of the Firm because both follow the comic formula of the guileful bumbler who succeeds in the end through sheer chutzpa. Now, it is hard to see the character Lubitsch played in these comedies, variously called Sally, Solly or Max, as anything other than a Jewish stereotype, an obvious point of controversy today. And while there is nothing subtle about Lubitsch’s performance, at least two things about Pinkus’s Shoe Palace suggest that there is more to the film than initially meets the eye.

Pinkus’s Shoe Palace (1916): a star is born

First, the film reflects a particular form of Jewish experience that was specific to Berlin at the time, which was, after all, the period of World War I. Lubitsch’s father was an émigré from the Russian Empire and so did not have full German citizenship, one ramification of his status being that his son was not a citizen either and so could not serve in the Imperial Army. Lubitsch was therefore exempt from conscription and free to pursue his stage and film career. Moreover, as eastern Jews or Ostjuden, the Lubitsches would have been further down the social scale than Berlin’s Westjuden. These western Jews had become more fully assimilated into German bourgeois culture and sought to distance themselves from the more overtly Jewish Ostjuden. The buffoonish character Lubitsch played in his store comedies may have confirmed the Ostjuden stereotype in some ways, but the security and sophistication the character achieves at the end of Pinkus’s Shoe Palace works against that stereotype. A second aspect of the film that makes it interesting today is the way it looks forward to Lubitsch’s later career. The director would return to the world of his youth in The Shop around the Corner (1940), one of his most charming and humane comedies. But in a more general sense the way Sally Pinkus goes from schoolboy prankster to urbane sophisticate (wearing spats, no less) suggests the arc of Lubitsch’s career as a director who goes from all those slapstick Lustspielen in Berlin to the stylish romantic comedies he made in Hollywood.

One aim of this book is understand how elements of Lubitsch’s German career might have found their way into his classic Hollywood films, an exercise that is easier to do with his comedies than with that other genre the director mastered in Germany: the historical epic, or, to use the German term, Kostümfilm (costume film). Such films as Madame DuBarry (1919), set against the background of the French Revolution, and Anna Boleyn (1920), about the ill-fated wife of Henry VIII, made Lubitsch’s reputation in Europe and prompted comparisons to D. W. Griffith, whose racist epic The Birth of a Nation (1915) established the guidelines of the genre: lavish costumes, huge sets, crowds of extras and some small-scale personal drama echoing the larger historical conflict. Giovanni Pastrone’s Cabiria (1914), an epic cinematic account of the Second Punic War (218–201 bce), also helped establish the genre, but in a late assessment of his career Lubitsch said his Kostümfilme ‘differed completely from the Italian school’. That school, he claimed, involved ‘a kind of grand-opera-like quality’, whereas he ‘tried to de-operatize my pictures and to humanize my historical characters’.3

Only recently have the films Lubitsch made during his German period come to be fully appreciated. There are at least two explanations for the phenomenon, the first aesthetic, the second political. First, most of the films Lubitsch made in Germany could not be placed in the context of the avant-garde cinema of the time, notably expressionism, that brand of art first manifest in painting that sought to capture images not as they were observed but as they were experienced, and not just by human beings. For example, the painter Franz Marc (1880–1916), the leader of the expressionist school known as Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider), asked, ‘How does a horse see the world?’4 The best-known cinematic effort to represent reality from the subjective perspective of the participant rather than from the objective view of an outside observer is Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr Caligari) (1920), which seeks to represent reality as it is experienced by an insane person.

The mise en scène of this film is distinguished by angular, distorted sets; dramatic, chiaroscuro lighting; and exaggerated, pantomimic acting. These features – especially the dramatic lighting effects – are supposed to reveal the influence of Reinhardt, according to the critic Lotte Eisner, who relegated Lubitsch to the second rank of German film-makers because he did not put his experiences with Reinhardt to expressionistic effect:

Lubitsch, who was for a long time a member of Max Reinhardt’s troupe, was less sensitive to his influence than other German filmmakers. A typical Berliner, who began his career with rather coarse farces, Lubitsch saw the pseudo-historical tragedies as so many opportunities for pastiche.5

The assessment is unfair: in fact, Lubitsch employed expressionistic devices in cinema before Wiene did, but he did so in one of his ‘coarse farces’ – namely, Die Puppe (The Doll) (1919), about a man who thinks he has married a life-sized female automaton, but which is, in fact, a real woman only pretending to be an automaton. Evidently, Lubitsch was not sufficiently serious to be included in the ranks of avant-garde, experimental film-makers, despite his seemingly endless capacity for cinematic innovation.

The Doll (1919): a real doll

The second likely reason Lubitsch’s German films have been underappreciated involves their political placement in what is undoubtedly the most celebrated theory about interwar German cinema, Siegfried Kracauer’s famous argument in From Caligari to Hitler (1947) that the films of the period unconsciously anticipated the authoritarian rule of Adolf Hitler. Kracauer cites The Cabinet of Dr Caligari, for instance, as a film that ‘glorified authority and convicted its antagonist of madness’, making Dr Caligari ‘a premonition of Hitler’, given the character’s ability to use ‘his hypnotic power to force his will’ upon others, as Hitler did ‘on a gigantic scale’.6 Although Kracauer names a few such authoritarian types in Lubitsch’s films, such as Henry VIII in Anna Boleyn, his main indictment of the director concerns his treatment of vast socio-political changes, such as the French Revolution, as the product not so much of historical forces as of personal psychology. Of Anna Boleyn, Kracauer says, the director ‘did not have to distort the given facts very much to make history seem the product of a tyrant’s private life’.7 Of Madame DuBarry (released in the US as Passion in 1920), Lubitsch’s film about the machinations of the titular mistress of Louis XV and her contentious relationship with Marie Antoinette, Kracauer says the ‘Lubitsch pageant […] drains the Revolution of its significance’:

Instead of tracing all revolutionary events to their economic and ideal causes, it persistently presents them as the outcome of psychological conflicts. It is a deceived lover who, animated by the desire for retaliation, talks the masses into capturing the Bastille.8

Poor Lubitsch is here accused of ‘degrading the French Revolution to a questionable adventure’, revealing the political ‘nihilism’ that is symptomatic of ‘strong antirevolutionary, if not antidemocratic, tendencies in post-war Germany’.9 Hence in Kracauer’s view, Lubitsch does not glorify authoritarianism so much as soften the ground for the tyranny to come by weakening belief in democratic institutions. From Caligari to Hitler was first published in 1947, the same year Lubitsch died, so the fact that Kracauer wrote without the benefit of later, more generous assessments of the director’s career may explain why his criticism is so severe. That criticism was not exactly borne out by the history Kracauer himself lived through, since the Nazis hardly embraced the man whose films supposedly predicted their rise to power. Kracauer does acknowledge that the Nazis ‘denounced Lubitsch for displaying “a pertness entirely alien from our true being”’,10 but, leaving aside the point that Madame DuBarry and the other historical epics could well be subjected to a range of political interpretations, it still seems strange that Kracauer would choose to ignore the well-known condemnation of Lubitsch during the Third Reich. After all, Hitler stripped Lubitsch of his German citizenship in 1935 and used his image as a representation of ‘The Archetypal Jew’ on posters in Berlin train stations. In 1940, footage of Lubitsch was used to help demonstrate the ‘degenerate’ nature of Jews in the notorious propaganda film Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew).11

Eisner’s and Kracauer’s negative criticism of Lubitsch’s German films notwithstanding, those films were enormously popular in Germany and eventually led to his entrée into the Hollywood studio system. The fame Lubitsch achieved as the ‘German Griffith’ reached the US when Madame DuBarry became one of the first films since the end of the war to break the xenophobic ban against the distribution of ‘Teutonic’ movies in the country. The success of that film and others prompted the star Mary Pickford to invite Lubitsch to Hollywood to direct her in a feature. Her brand as ‘America’s Sweetheart’ had begun to fade, so she looked to Lubitsch to take her career in a different direction. At first the vehicle of choice was to be Dorothy Vernon of Haddon Hall, a historical novel of 1902 set in Elizabethan England (Pickford made the film with another director in 1924), but Lubitsch persuaded her to take the title role in Rosita (1923), a story about a Spanish street-singer set in the eighteenth century that he had already begun to develop with his long-time screenwriter Hanns Kräly back in Berlin. So while Lubitsch’s costume dramas helped him get to the US, it is hard to see in them that combination of elegance and ellipsis that so distinguishes later comic romances like Trouble in Paradise.

One possible explanation for the turn in Lubitsch’s career towards elegant understatement is his openness to the new direction in narrative cinema suggested by Charlie Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris (1923), which Lubitsch saw after completing Rosita, just as he was gearing up to make The Marriage Circle (1924). Chaplin’s film disappointed audiences because his beloved Little Tramp character was nowhere to be seen (Chaplin appears briefly in the film in a Hitchcock-like cameo). Subtitled A Drama of Fate,...